Alpine Capital Research commentary for the third quarter ended September 30, 2022 titled, “Locking in Profits.”

Q3 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Locking in Profits

A bear market bounce in the first half of the third quarter devolved into a “recession-on” market decline in the second half, with the quarter ending at year-to-date lows. Market fluctuations like these are likely to be soon forgotten, assuming they represent temporary volatility rather than permanent loss. Despite current bear market ups and downs, the average ACR portfolio company accrued earnings this quarter as usual. More happily, rather than experiencing permanent loss, ACR investors likely established meaningful future gains as our idle cash was deployed into bargain purchases. ACR strategy results can be found at https://acr-invest.com/strategies/.

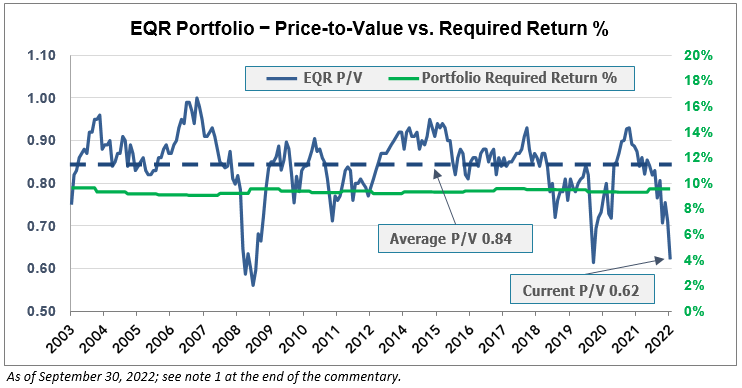

Our job is to buy quality companies at low prices. This is why we welcome short-term price declines. The EQR strategy price/value chart below indicates that prices today have reached historic lows relative to values.1 “Value” is based on our subjective appraisal of fundamental company net worth, stemming from our estimates of future company cash flows. To get value right, we must get future cash flows right. Our results since inception in 2000 show we have gotten future cash flows sufficiently right in the past. While confident in the cash flow assessments of our portfolio companies today, only time will tell if our estimates will be on target once again.

Fundamental value estimates are always in relation to an investment return. That is, valuation works in three steps: establish the return desired for the risk taken, estimate future company cash flows, and use these figures to solve for value.2 If a lower return is required, then fundamental value and the price an investor would be willing to pay are higher. Importantly, ACR never lowered our required return with lower interest rates, which is shown in the EQR price/value chart as the “required return.” This is why we do not fear higher interest rates—a topic on which we will have more to say momentarily.

The upshot is that if we have assessed the future cash flows of our holdings correctly, future returns should equal the required return plus the price/value discount rising to 1.00. A current required return of 9.6% plus a historically low price/value of 0.62 implies an attractive return from today’s prices.3 Again, it must be emphasized, we must get the cash flows right. Garbage-in, garbage-out; quality-in, quality- out—the distinction is everything. Stated defensively, then, the price/value discount is a margin of safety, which helps assure that we earn our stated required return.

Fundamental value and future cash flows often have little to do with short-term prices. Market prices could decline significantly over the next year. Watching account values seemingly vanish into thin air is understandably a harrowing experience for any investor. Extremes such as those of 2008-09 can leave emotional scars, even for the most confident ACR client. The investment team does not know how bad the current market will get. We do know that the companies in our EQR strategy have been analyzed and selected to sustain depression-like conditions, even though we think the likelihood of economic catastrophe is remote.

Many investors speculate on price. In our opinion, this is the grand illusion of public-markets investing. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could predict next year’s prices? Just as wonderful as if we could read next year’s newspaper. Rather than coming up with fanciful ideas about prices, ACR strikes when company profits can be bought cheap. We do not speculate on what the Fed will do and when, do not attempt to call when recessions will begin or end, nor do we try to time market bottoms. We believe these are distractions at best, dangerous pitfalls at worst. Striking when value is cheap means we are often early. The prices of some companies that we buy go down further after we buy them. The key point remains: if we lock up the right price at purchase and get future company cash flows right, then we will have locked in an attractive return regardless of short-term declines.

Getting company cash flows right means we need to correctly assess economic opportunities and risks. Major big-picture risks today are rising interest rates, inflation, recession, and war. ACR has been discussing the problem of ZIRP (zero-interest-rate policy) since 2013: a fed funds rate at or near 0% combined with quantitative easing (lowering long-term interest rates) has, in our view, produced inflated asset prices. The question has always been: what happens when interest rates rise? Today we are finding out. As previously noted, ACR never lowered our standards by assuming lower required returns to allow for higher purchase prices. Therefore, we are not concerned about today’s declines turning into permanent losses or disappointing long-term returns, as we would if we did not have such discipline.

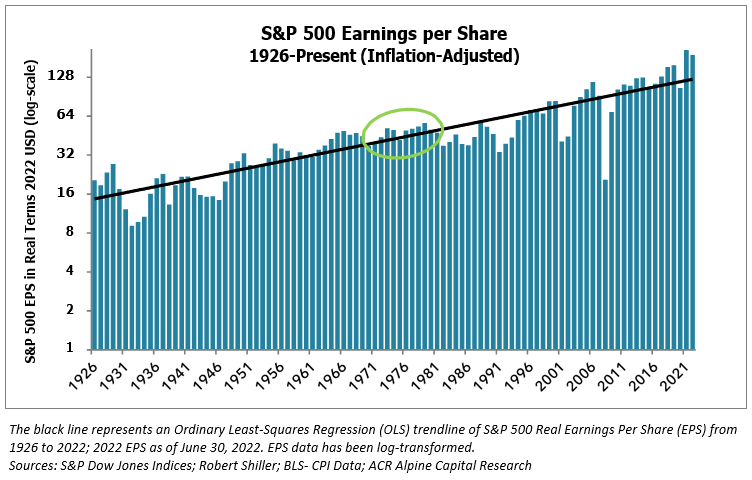

Inflation is the reason for higher rates. In our 2021 second-quarter commentary, Inflation, Markets and Returns, we discuss how company profits are a hedge against inflation. Companies capable of increasing revenues with costs, by definition, protect against inflation. The secondary issue is whether stock prices keep pace with inflation. Pointing to a 2001 paper by James R. Lothian and Cornelia McCarthy entitled “Equity Returns and Inflation: The Puzzlingly Long Lags,” stock prices eventually track earnings and are therefore a hedge against inflation in the long term.

“Inflation, Rational Valuation and the Market,” a paper published in the 1979 March/April Financial Analysts Journal by Franco Modigliani and Richard A. Cohn, addresses Lothian’s “puzzlingly long lags” while supporting a view we have long held. (Warning: the abstract below, and the three paragraphs that follow, contain technicalities suitable only for asset-pricing propeller heads.)

In the paper’s abstract, Modigliani and Cohn summarize their case:

The ratio of market value to profits began a decline in the late 1960s that has continued fairly steadily ever since. The reason is inflation which causes investors to commit two major errors in evaluating common stocks. First, in inflationary periods, investors capitalize equity earnings at a rate that parallels the nominal interest rate, rather than the economically correct real rate – the nominal rate less the inflation premium. In the presence of inflation, one properly compares the cash return on stocks, not with the nominal return on bonds, but with the real return on bonds.

Second, investors fail to allow for the gain to shareholders accruing from depreciation in the real value of nominal corporate liabilities. The portion of the corporation’s interest bill that compensates creditors for the reduction in the real value of their claims represents repayment of capital, rather than an expense to the corporation. Because corporations are not taxed on that part of their return, the share of pretax operating income paid in taxes declines as the rate of inflation rises. For the corporate sector as a whole, this effect tends to offset any distortions resulting from basing taxable income on historical cost. If a firm is levered, inflation can exert a permanently depressing effect on reported earnings – even to the point of turning real profits into growing losses. On the other hand, a firm that wishes to maintain the same level of real debt despite inflation must increase its nominal debt at the inflation rate; the funds obtained from the issues of debt needed to maintain leverage will precisely equal the funds necessary to pay interest on the debt and maintain the firm’s dividend and reinvestment policies.

Rationally valued, the level of the S&P 500 at the end of 1977 should have been 200. Its actual value at that time was 100. Because of inflation-induced errors, investors have systematically undervalued the stock market by 50 percent.

Modigliani and Cohn’s first point is that investors confuse the nominal and real required return. That is, they valued stocks during this high-inflation period using the higher nominal rather than lower real rate. This caused them to undervalue stocks at the time. ACR has disaggregated nominal and real required returns and earnings growth since our inception in 1999, to be clear on this subject. We also point out this problem in our 2013 second-quarter commentary, The Low Rate, High Profit Value Mirage. While we would argue that the real discount rate should be contingent on long-term rather than short-term real rates, the essential point is to value stocks based on the investor’s estimate of real, rather than nominal, yields.

Just as investors got it wrong undervaluing equities during the great inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, we believe they have overvalued equities during the ZIRP era. Ominously, we could be in the early innings of a major adjustment process, similar to Modigliani and Cohn’s observation in 1979 that valuations began contracting with rising rates in the late 1960s. ACR investors should not be materially affected by this adjustment process as it regards our return estimates, as we did not make the mistake of valuing companies with permanent, artificially low nominal rates.

Modigliani and Cohn’s second point regarding the positive effects of inflation on debt—which we incorporate in our valuations—is an interesting mitigant to the negative effects of inflation on after-tax returns discussed in Inflation, Markets and Returns.

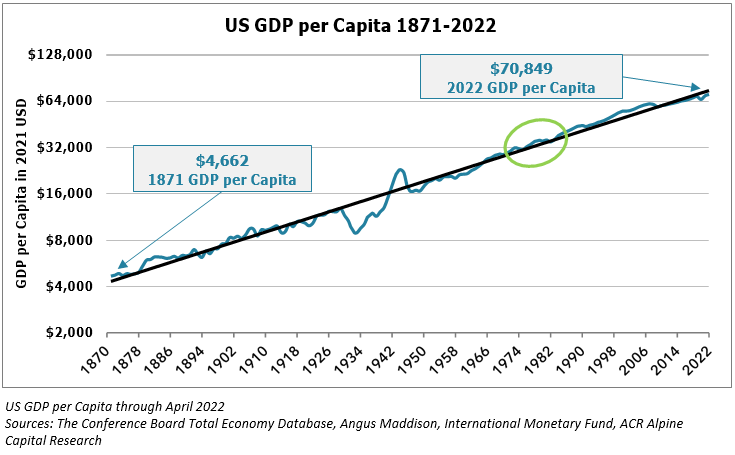

Two charts will help to summarize our thoughts on inflation: real GDP per capita growth and S&P 500 earnings. The inflationary period from 1969-1982 is circled in green to demonstrate that neither economic productivity nor real corporate profits were meaningfully impaired.

Our discussion of economic risks has centered on inflation, the topic du jour. War and recession are equally as important and complex. For the sake of brevity, however, we will relegate a more detailed discussion of each to future commentaries, while summarizing our overarching approaches now.

Nuclear-armed Russia’s aggression is, in our opinion, the greatest risk to the world economy today. While we will always work to understand each company’s risks and opportunities during wartime, our general recipe for protection against war is the same as for protection against depression: own quality companies without too much leverage. One must also remember, while war has been a tragic perennial in human history, the global economy has continued its long-run ascent.

Regarding recession, ACR bakes the typical economic contraction into our company-level valuations. A more severe recession could reduce our valuations but should not impair future returns. Upcoming commentaries will explain how we incorporate recession into our valuations, including the art of adjusting earnings for the economic cycle.

Nick Tompras

October 2022