Kerrisdale Capital is short CareDx Inc (CDNA).

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

We are short shares of CareDx, a $1.7bn diagnostics company whose share price has increased by 30x over just the last two years and now trades at over 18x sales. The meteoric rise and generous valuation have come in the wake of excitement over the commercialization of AlloSure, a blood test intended to identify organ rejection in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant nephrologists have long used measures of kidney function to assess the probability of rejection, with a tissue biopsy providing a definitive diagnosis. To hear CareDx tell it, AlloSure is the long sought-after silver bullet for rejection diagnosis, with the potential to “revolutionize the treatment of kidney transplant patients.” It can help physicians “detect rejection of a donated organ earlier and more accurately” than traditional blood-based measures of kidney function and “reduce the use of invasive biopsies.” [emphasis added]

But alas, as hard as CareDx has tried to finesse the numbers into telling a good story, it’s difficult to escape the simple fact that AlloSure is mostly useless, and potentially dangerous if used improperly. It should be obvious that a diagnostic test for transplant rejection that misses about 40% of rejections compared to the current standard of care has little place in clinical practice. But the stars have fortuitously aligned for CareDx: under the financial cover of broad (but provisional) Medicare coverage, the company has enlisted dozens of influential transplant researchers in the country’s largest clinics to conduct numerous large-scale studies evaluating AlloSure. The hope is to conclusively proclaim its status as a diagnostic panacea.

The data coming out of those studies, though, is exceptionally poor, even as AlloSure revenues are overwhelmingly comprised of utilization in those studies. That leaves CareDx in a precarious position, particularly as physicians wise up to the futility of AlloSure. We calculate that CareDx has faced a quarterly attrition rate on AlloSure’s surveillance patient population of 20-30%. That’s staggering for a diagnostic test with a captive patient population, particularly one that’s paid for almost entirely by Medicare. It’s perhaps less surprising when viewed in the context of the continuous trickle of papers and data revealing AlloSure’s futility in identifying the most common types of kidney rejection.

That data will present an even bigger obstacle for CareDx when Medicare reconsiders its coverage parameters, which are conditional on the results of a large clinical trial under way. It’s already clear, in our view, that AlloSure won’t be able to serve as a diagnostic tool in the way it was originally envisioned, which would jeopardize Medicare coverage. It’s therefore unsurprising to see that, in an attempt to stay relevant, recent AlloSure research sponsored by CareDx has been pivoting hard, aiming to prove AlloSure’s worth in a subset of the overall kidney transplant market. The problem, as we shall see, is that the subset being targeted is a fraction of the $2 billion that CareDx has declared its addressable market.

To make matters worse, several competing rejection diagnostic tests are slated to hit the market in the next few months, fresh off their own provisional Medicare coverage approvals. Some have similar mechanisms of action as AlloSure but promise to be more accurate and potentially cheaper. Others have novel mechanisms based on genomic markers and are backed by impressive clinical evidence. They will now get the chance to vie for their own place in clinical studies, and we expect them to hasten the unraveling of AlloSure that’s already under way. CareDx, reliant on a single ineffective test, will soon confront its own terminal diagnosis.

I. Investment Highlights

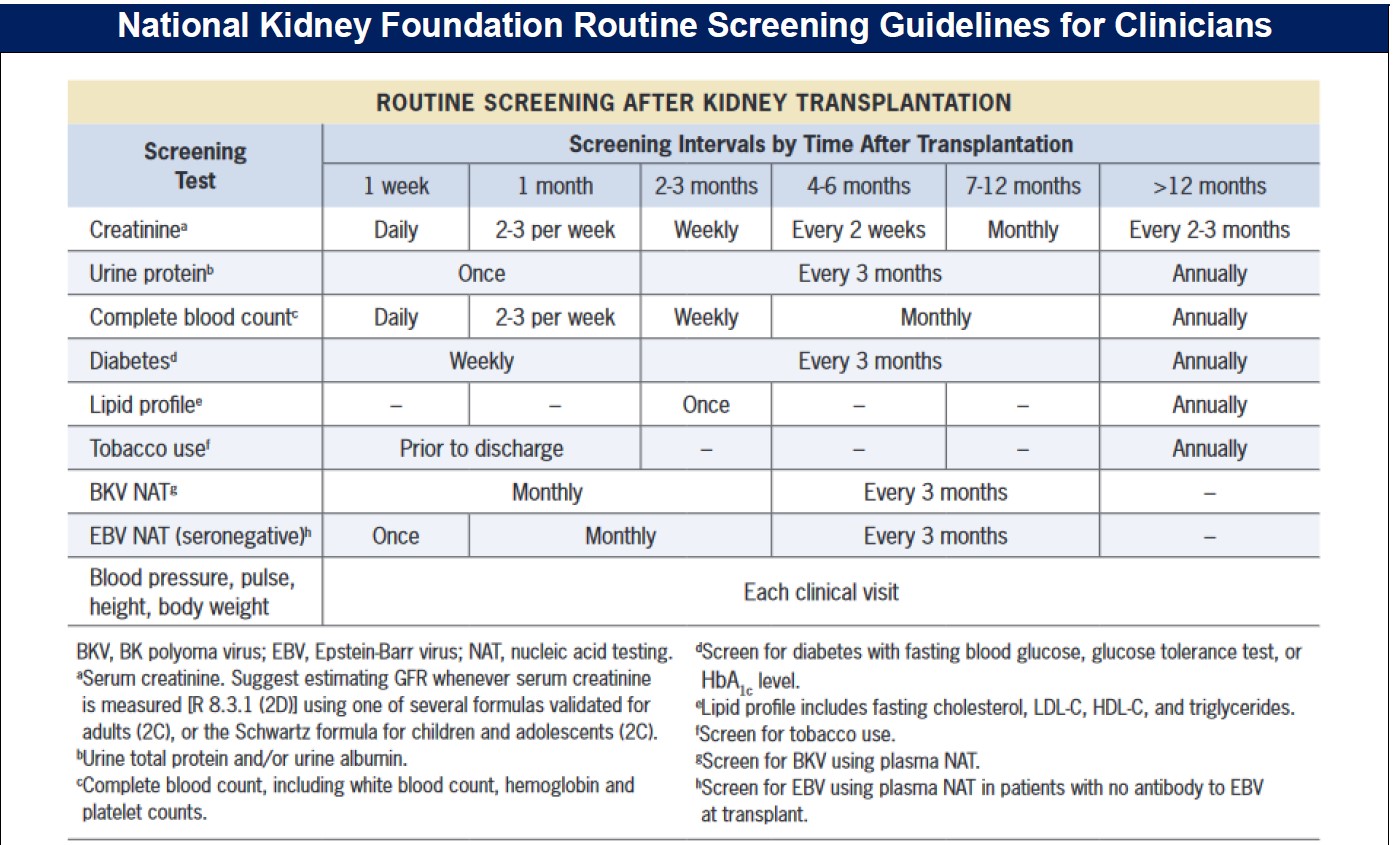

AlloSure is ineffective in identifying kidney rejection. The gold standard of kidney rejection diagnosis for transplant recipients is a biopsy. Kidney transplant recipients are subject to ongoing monitoring post-transplant, during which they undergo routine screening to assess kidney function. Abnormal serum creatinine or, less frequently, high urine protein levels are typically the first sign(s) of decreased kidney function. If they lead to suspicion of rejection, a biopsy is performed and examined in order to determine whether the kidney is suffering from rejection.

But creatinine is an admittedly flawed marker:

- False Positive Rate. Creatinine levels are an indicator of kidney function, and rejection is just one of several reasons they may be elevated. As a marker of kidney rejection, the false positive rate is high, as only about a third of biopsies that are performed due to elevated creatinine are diagnosed as rejection.

- False Negative Rate. Rejection can occur with no short-term loss of kidney function, and creatinine measurements are incapable of picking up rejection in such cases. This phenomenon, called “subclinical” rejection, is estimated to occur in 15-35% of transplant recipients that have normal creatinine measurements.

The field of nephrology has long pursued a noninvasive biomarker of kidney rejection that would a) eliminate the false positive problem, thereby reducing unnecessary biopsies and b) detect subclinical kidney rejection. AlloSure – the diagnostic test responsible for most of CareDx’s market capitalization – is the first attempt (but certainly not the last) to commercialize such a biomarker. In CareDx’s telling, AlloSure provides “precise, actionable results” and is “more accurate than serum creatinine in diagnosis of active rejection.” It also provides a “sensitive, accurate, and precise measure of organ health.” We believe that the underlying message – that AlloSure is a precise method that can be used to establish the presence or absence of kidney rejection – couldn’t be further from the truth.

Every single clinical paper and study of AlloSure leads, in our view, to one inescapable conclusion: AlloSure is an utter failure as a comprehensive biomarker of rejection. In fact, based on the flagship paper1 used by CareDx to demonstrate the test’s clinical utility, doctors using AlloSure to rule out rejection, as per the company’s marketing materials, would miss about 40% of rejection episodes that would otherwise be detected using the current standard of care. In the course of our diligence we found that in some clinics doctors have begun using AlloSure to diagnose rejection, and we believe this puts a significant number of kidney transplant recipients at unnecessary risk. Abnormal creatinine levels may overdiagnose rejection (high false positive rate), but AlloSure presents the much more severe problem of underdiagnosing rejection (high false negative rate).2

What about subclinical rejection, which goes undetected by creatinine measurement? In CareDx’s DART clinical trial, only 3.9% of a reference cohort of patients who exhibited no signs of impaired kidney function tested positive for kidney rejection using AlloSure.3 But studies documenting the results of surveillance biopsies reveal that the subclinical rejection rate ranges from 15-35%. In other words, AlloSure misses the overwhelming majority of subclinical rejection episodes, and that’s ignoring the false positives in that 3.9% number.

More recent studies confirm the problems with AlloSure implicit in the DART trial and cast further doubt on the accuracy of the test, strongly suggesting that AlloSure is structurally incapable of identifying T-Cell-Mediated Rejection (TCMR), by far the most common type of acute rejection. The consistent weakness of AlloSure across multiple studies is that, in statistical parlance, its sensitivity – the probability that the test result will be positive given the occurrence of rejection – is so low as to make the results unreliable at best, and dangerous if misused.

AlloSure’s commercial success is unsustainably built on collapsing clinical-study usage and conditional Medicare coverage. If AlloSure is such a poor biomarker, how did it reach a ~$45 million annual revenue run rate in less than 18 months? As a Laboratory Developed Test (LDT), the only barrier to commercialization was payor coverage, and over 90% of kidney transplant procedures qualify for Medicare coverage, which includes all medical care for 3 years post-transplant. So the only third party payor that really matters for AlloSure (for now) is Medicare, which is fortunate because LDTs can obtain broad Medicare coverage just by competently navigating the MolDX program.

MolDX, short for Molecular Diagnostic Services, is a program run by Palmetto GBA, a Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) in the Southeast, and set up in 2011 in order to manage the growing number of genetic and molecular diagnostic LDTs. Most of the MACs have outsourced their LDT coverage decisions to MolDX, so the program is effectively a gateway to national coverage and reimbursement for any LDT. To get a Local Coverage Determination (LCD) from MolDX, a test must pass a technical assessment, which involves subject matter experts determining whether it has demonstrated “analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility.”

MolDX will normally grant an LCD even with limited evidence of clinical utility, conditional upon further research that is expected to prove clinical utility. The LCD for AlloSure states that MolDX “recognizes that the evidence of clinical utility for the use of AlloSure in its intended use population is promising at the current time. However, this contractor believes that forthcoming prospective clinical studies will demonstrate improved patient outcomes. Continued coverage for AlloSure testing is dependent on annual review by this contractor of such data and publications.” [emphasis added] For now, though, AlloSure is covered and reimbursable for any kidney transplant recipient covered by Medicare.

That LCD went into effect on October 2, 2017, which partly explains the AlloSure revenue ramp that started in the fourth quarter of 2017. But it’s also worth putting AlloSure into the more general context of organ rejection research. The transplant community has always dreamed of a noninvasive “silver bullet” to detect organ rejection, and the genomic revolution has brought with it hope that such a test could be developed. AlloSure measures the quantity of donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA) in the patient’s blood stream, and the hypothesis that cfDNA might signal organ rejection was first advanced as far back as 1998. Research on the matter started gaining momentum in 2011 and, since then, small studies of cfDNA as a rejection marker in heart, lung, and kidney transplants showed promise but were inconclusive. Even the March 2017 flagship paper that arose out of CareDx’s DART study was small (102 patients, only 27 of whom were diagnosed with rejection) and while “promising” (in the words of MolDX), it was far from conclusive.

The LCD from MolDX in late 2017 essentially subsidized further studies of cfDNA by providing reimbursement for AlloSure, which flung open the door for large-scale studies to take place. cfDNA, which had been the subject of intense speculation and curiosity for a decade, could now be studied as a noninvasive rejection biomarker in large numbers and at negligible cost. On top of the latent demand for studying cfDNA, CareDx shrewdly provided financial support and funding to renowned transplant nephrologists in over two dozen of the largest clinics nationwide, ensuring a steady stream of multi-year studies that would provide “recurring” demand for AlloSure tests. The company also immediately began enrollment on a massive 1000-patient clinical trial (KOAR), which, in the company’s own words, would “include approximately 10,000 reimbursed AlloSure tests over the next 3 years, thus representing incremental AlloSure volume as well as another revenue driver going forward.”4

As with the routine screening of transplant recipients (see below), AlloSure usage is being studied on a protocol basis, with CareDx routinely disclosing on earnings calls the number of patients on an AlloSure surveillance protocol. Recently, the company has disclosed a quarterly attrition rate of 10% for these surveillance patients. While that still implies an incredible 35% annual drop-out rate, we believe that the real attrition rate is much higher. Given the historical disclosure of quarterly surveillance patients, and recent disclosures regarding the total number of patients who have ever been provided AlloSure results, we calculate an attrition rate for surveillance patients of approximately 20-30% per quarter, or a staggering 70% annually. Consider that CareDx has provided results to “over 8,000 patients” in the span of 6 quarters, and yet only about 3600 patients are currently on an AlloSure surveillance protocol.

The disclosures also suggest that over 90% of AlloSure revenue comes from these surveillance patients. Ironically, AlloSure’s revenue comes almost entirely from transplant clinics studying it as a routine screening tool, but finding it so inadequate that they rapidly drop it. We expect the patient recruitment treadmill will soon become impossible to outrun.

Source: National Kidney Foundation: Managing Kidney Transplant Recipients

Read the full report here by Kerrisdale Capital