What is a bias?

While the word certainly carries a negative connotation, it is essentially a preconceived opinion or feeling. Sometimes these opinions are based on accurate, objective and balanced information. Other times, they are based on inaccurate or isolated information.

[REITs]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Our minds create biases throughout our lives. They are based on our experiences, with the goal of improving and quickening our decision making process. For example, if you witnessed a motorcycle accident when growing up, you may have formed a bias against motorcycle riding (likely a beneficial bias). Or if you capitulated and sold during the bear market of 2008-09, we are pretty sure you would have a strong negative bias towards investing (unfortunate given the 10 year market recovery).

We all use our biases to reach decisions. This helps us make many decisions each day without having to go through a pain staking endeavor of a drawn out cost / benefit analysis, weighing all the options and possible outcomes. It becomes an issue when our biases are founded on inaccurate or isolated information, and this causes us to come to a wrong conclusion. When you add elevated emotions, biases tend to have a bigger impact on our decision making.

Investing is an emotional undertaking. The stakes are high as it impacts our long term lifestyles and there is a high degree of uncertainty. This environment is ideal for our behavioural biases to impact decisions. Yet it gets even more complicated. We all have different biases based on our own experiences in life and the impact of these biases also changes depending on the situation.

In a recent Market Ethos we explored the behavioural biases that most often impact the decision making process of investment advisors or other investment professionals. The folks who spend the majority of their day in the world of finance providing advice or managing money (HERE). In this report we will highlight a number of biases that have often impacted the investment decision making process of investors. Plus provide some tools to better manage those biases, with the goal of making more objective, better decisions, and hopefully more wealth.

Loss Aversion

In the world of behavioural finance, loss aversion is one of the biggies. Associated with prospect theory which found we feel the pain of losses to be far greater than the pleasure of an equal sized gain. This may sound a bit abstract, and perhaps the chart to the right doesn’t help much, but loss aversion impacts many investors decision making.

Since we dislike losses, it can cause us to hold onto losing investings too long, in the hopes it will recover. This is often referred to as ‘get-even-itis’. It can also lead investors to sell their winners too early, attempting to avoid the pain caused in case the share price falls back down.

Consider if you owned two investments, one has done well while the other has not. Now you have to sell one. Selling the winner would be a ‘win’, you made money and it would remove the risk of the round trip where the share price falls back to the level you initially invested. Selling the loser turns a paper loss into a real one (yuck). Plus, what if it recovers, you will feel the fool.

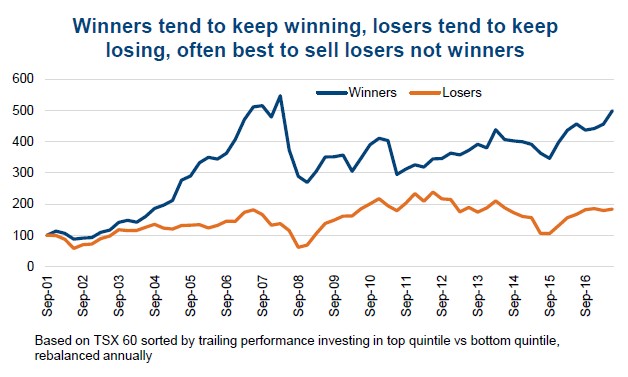

Unfortunately, this thought process can really hurt returns over time. The top chart based on the index members of the TSX 60 each year, sorted by trailing 1-year performance and tracked the performance for the subsequent year. Essentially capturing the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. As you can see, the winners tend to keep winning while the losers don’t seem to recover all that much. This is statistical evidence that should help encourage investors to cut their losses and let their winners run longer.

How to defend against loss aversion – A significant portion of loss aversion is rooted in Anchoring and Sunk Cost bias. This is basically making decisions based on the original cost of investment. Ignoring the original cost can help offset this bias. After all, it is the current market value and future prospects of an investment that truly matter, the stock or fund doesn’t know or remember what you paid for it. Obtaining a second opinion on an investment also helps. While the person you ask has biases too, they won’t be emotionally vested or anchored by what you paid and they are likely to have different biases. Another tool that can help is documenting the original thesis or rationale for an investment. If it still holds, even if down in price, this investment is typically fine to hold on. If the situation has changed, and the thesis is no longer valid, usually best to cut and run.

Performance Chasing

This isn’t a behavioural bias but is the end result of a number of biases including Overconfidence and Herd Behaviour.

Overconfidence: Overconfidence is the tendency to believe past performance is evidence of a superior manager. While this may be the case, more often it is the manager’s style being well rewarded in the current market environment.

For example if two U.S. equity funds had trailing 3-year annualized performance of +20% and +8%, you may jump to the conclusion that the first manager is simply better and invest in that one. However, if the first is a growth manager and second a value tilted manager, this is more a case of the market rewarding growth over value than one manager being better than the other.

Herd Behaviour: The financial industry encourages this behaviour and does little to limit its impact on investment results. You may have noticed the popularity of those charts showing how much $10k would have grown over a number of years invested in a fund. This is attempting to lure you in by implying the herd is doing so well, you just need to join.

The problem is that the investment styles rewarded in the market tend to change from year-to-year and chasing the best trailing performance can have a negative impact on returns as the market dynamics change. The second chart on this page is the return of the market, the average fund return which is a little lower due to fees, and the dollar weighted investor return. Much of this drop in performance from fund to actual investors returns is caused by investors piling into a fund only after it has had a strong performance run.

Article by Craig Basinger, Chris Kerlow, Derek Benedet, Shane Obata – Richardson GMP