FPAFund’s special commentary for the month of January 2019, titled, “Risk Is Where You’re Not Looking.”

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

“To expect the unexpected shows a thoroughly modern intellect.” – Oscar Wilde

Most of us worry. We understand logically that we perhaps imagine more issues, problems and crises than actually will occur, but that doesn’t stop us from worrying just the same. Our concerns generally encompass what we’ve seen happen before, particularly what has happened more recently.

We Californians, for instance, weren’t so terribly concerned about fires five years ago. But having witnessed many devastating fires since then, we’re now more painfully aware of the risk of living here. Fires are now something we worry about and try to prepare for accordingly.

We expect, in other words, what happened last time or the time just before that – but risk is generally not where we anticipate. Take the citizens of Pompeii, who weren’t worried about Mount Vesuvius erupting in 79 AD. The volcano hadn’t erupted in almost 1,900 years, and so most, if not all of those living at its feet didn’t know it had ever erupted at all – literate Greeks arrived in the area, which was inhabited by tribes that had no written language, only in the 8th century BC. So understandably, the Pompeiians failed to anticipate the risk that Vesuvius would erupt, and they paid for that blindness with their lives.

For the most part, we can only worry about what might erupt next if we know the horrors of a previous eruption or conflagration, and fortunately, we do have historical records and, for many of us, personal recollections of what happens when companies, governments and people take on a lot of debt.

And so leverage, particularly lower quality, burgeoning corporate debt, is the area we will focus on here because of such memories and history. We will consider both the absolute level of leverage as well as the probability that assets and earnings may be insufficient to fully meet current obligations.

Investors attempt to move forward using their rear view mirror for direction, giving more weight to what has happened than what might. A decade ago, the US consumer carried too much debt. At the same time, US and European banks suffered with too little equity to absorb the losses of poorly underwritten loans – the left side of the balance sheet wasn’t right, and the right didn’t have much left. Overzealous homeowners and speculators, aided and abetted by shameless bankers, fostered and exacerbated the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09.

At First Pacific Advisors, we avoid using the rear view mirror except when we intend to go in reverse. We prefer instead to look forward through our windshield, despite it being dusty and cracked.

We believe that sovereign and US municipal governments and corporates are more the problem now and that their excessive leverage will either catalyze or magnify the next downturn. The current debt trajectory, in terms of levels and quality of credit, is unsustainable and will inevitably end. Understanding this today will hopefully protect the capital of our investors in the future.

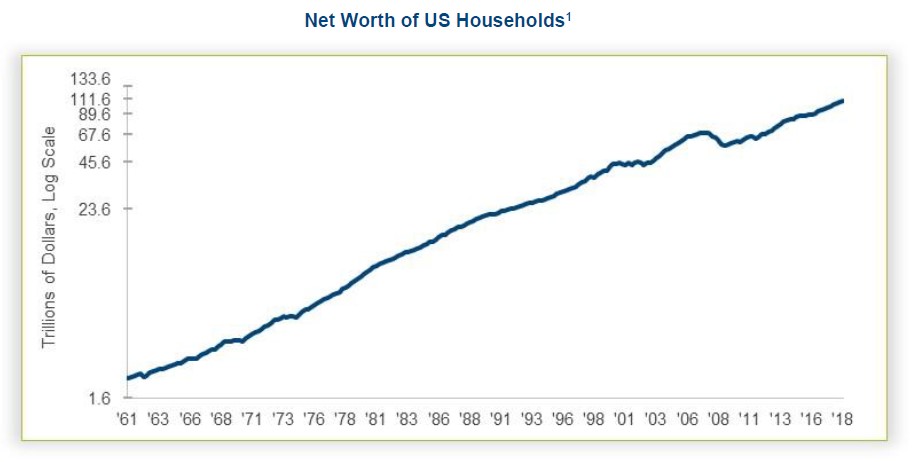

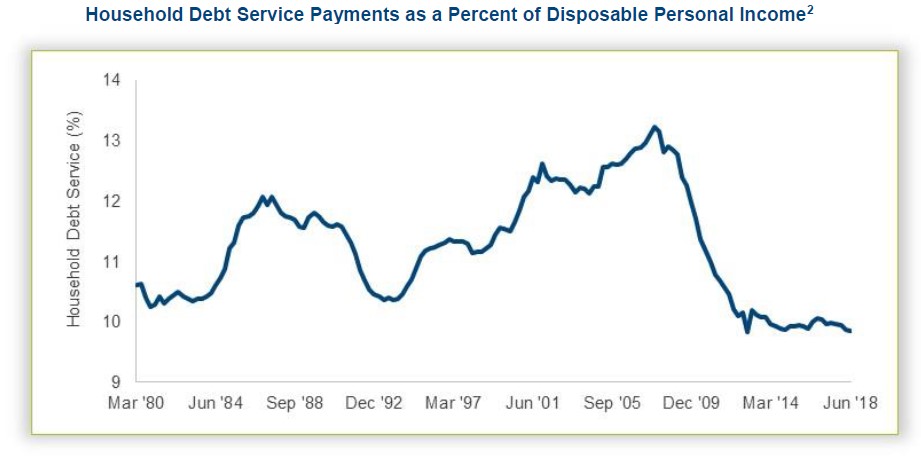

The average American today appears to be in relatively good financial shape. Household net worth in the United States is at a new high, and debt service payments as a percent of disposable income is at a four-decade low, as exhibited in the following graphs.

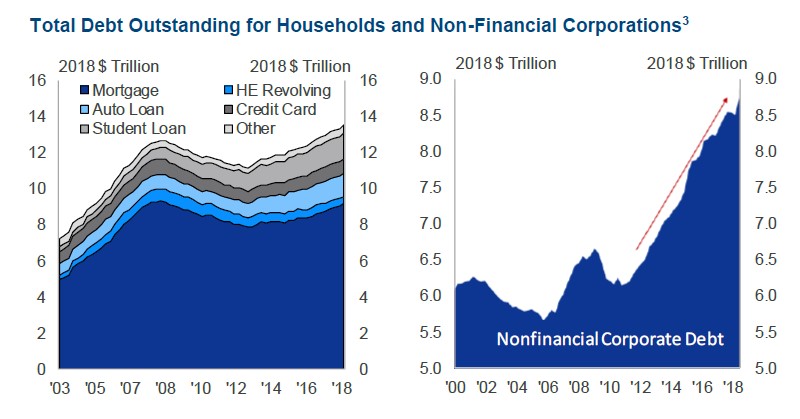

US households have slightly higher debt than the last recession (below left), but thanks largely to home price appreciation and, as pointed out above, their net worth is higher. Their stronger financial position, though, has been replaced by the weaker financial position of a more leveraged Corporate America (below right).

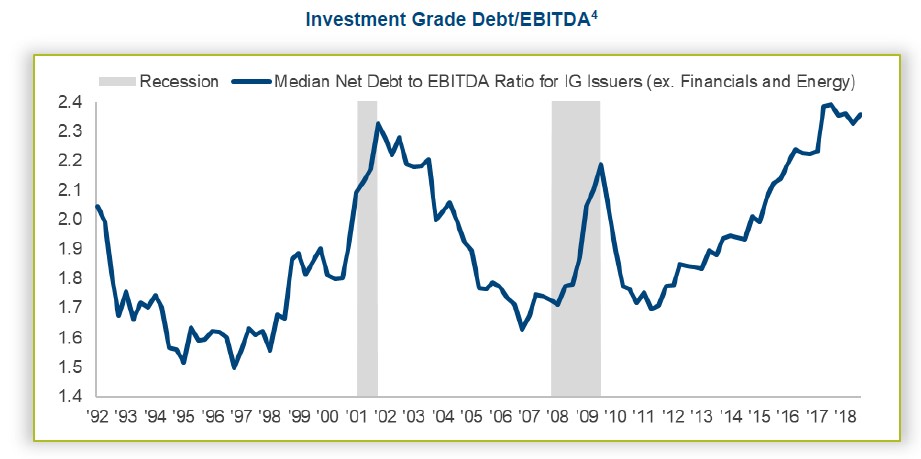

While this has left the US consumer with a less onerous financial burden relative to income, “conservative”

investment grade bonds have almost the most leverage in at least the last quarter century.

The other broken pillar in the Great Financial Crisis, the big US banks, also is in a much better financial

position today, with more equity to support what we believe are better quality loans. The market capweighted

average level of tangible equity to total assets of S&P 500 banks is 8.8%, up from 5.4% in 2008,

while their non-performing loans have declined from 5.0% in 2008 to 1.1% as a percent of total loans during a similar period.5,6 This stands in stark contrast to the many European banks that have neither taken necessary loan write-downs nor built necessary equity. European banks have equity that is still only at 2008 US bank levels (5.4% in 2018 vs 3.7% in 2008), and the percentage of their loans that are non-performing is higher (3.7% in 2017 vs 2.8% in 2008).7,8

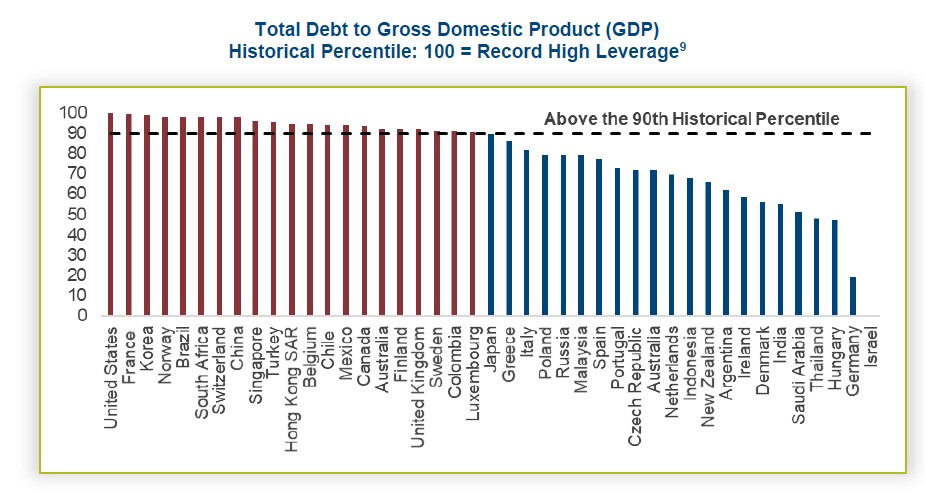

Additionally, the average nation now carries more debt than it has historically. Most significant countries as measured by size of economy sit at or above the 90th percentile of their historic debt-to-GDP ratio. More debt today means higher interest payments and less flexibility in the future.

To be sure, the increase in sovereign debt has aided global economic growth, but we believe it is unlikely to continue to boost economies in the same way it has in the recent past. Sovereigns will have their denouement, and in some cases, leaders may choose to inflate their way out of the debt strait jacket. At the very least, many countries may come to resemble the zombie corporations we address further on in this commentary and find their economic growth imperiled by an inability to increase already bloated debt levels and/or be forced to pay the higher financing costs that induce recession.

One does not have to look back any further than the recent travails of Greece. Higher borrowing costs and a deep recession led the market to realize that the country’s total debt burden, a combination of sovereign debt, pensions and so forth, was unsustainably high. This led to riots, political upheaval and, of course, declines in the price of Greek sovereign debt. Holders of Greek bonds (other than the European Central Bank) ultimately received mere cents on the dollar.

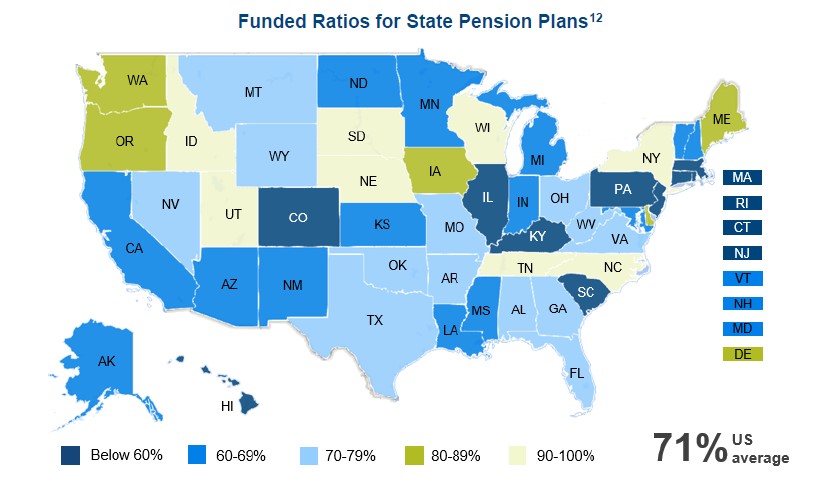

High levels of government debt in the US is not a federal issue alone. State and local governments are weighed down by huge debt loads and unfunded pension liabilities. Meredith Whitney conducted thoughtful municipal research in 2010, lamenting the sad state of municipal affairs and anticipating widespread municipal bankruptcies.10 When asked why people seemed oblivious to the problem in a 60 Minutes interview, she responded, “Because they don’t pay attention until they have to.”11 We appreciated the problem then as we appreciate the current problem, but just as before, we have no ability to ascertain timing, thanks to changing tax policies and the long-term nature of off-balance sheet liabilities like pension obligations, infrastructure spending and the like. Nevertheless, horribly weak balance sheets at the state and local level, depicted in the chart below, may ultimately become manifest in the form of additional Chapter 9 bankruptcy filings at the municipal level.

As we said, the question of timing eludes us (again), and we appreciate that merely pointing out challenges that might face us due to excessive government leverage is an exercise in incompleteness. Sometimes, though, mentioning an issue piques a reader’s interest and fosters additional consideration.

Our aptitude squares better with corporate debt, and thus corporate debt is the focus of this piece.

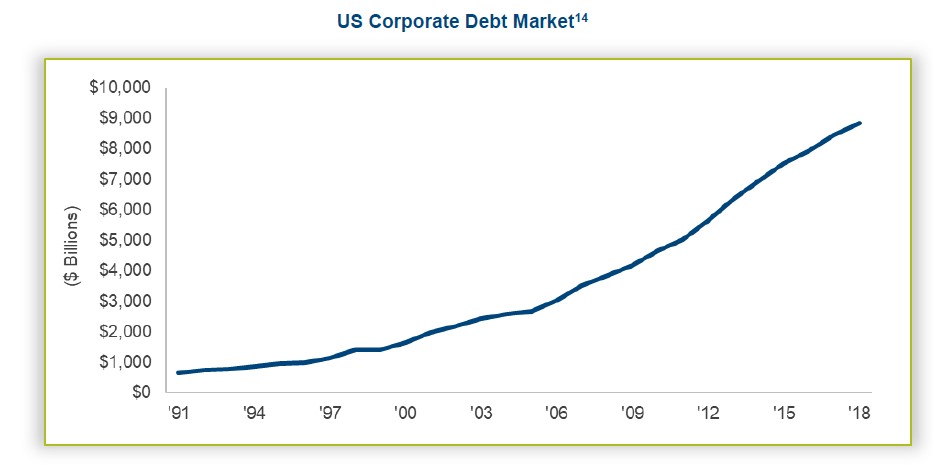

The sum of US corporate bonds outstanding totaled $3.8 trillion in 2008 and has since more than doubled to the current $8.8 trillion.13 This 8.8% annual rate of increase is more than two times GDP growth in that same period. The increase has aided corporate mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”), leveraged buyouts and share repurchases and supported to some immeasurable level the growth in corporate earnings, all of which have served as drivers of US stock market returns. But we think it’s safe to say at this point that there won’t be the same continuing demand for corporate debt to provide the same stimulus in the future.

Corporate debt is now at an all-time high as a percent of gross domestic product.

Corporate debt cannot continue to grow faster than the economy forever, and when it slows, the more recent strength in the economy and stock market will lose a significant engine of growth.

This begs a moment to reflect on the drivers of corporate debt growth.

Banks curtailed lending after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09, and rumblings about the fragility of our banking system continue in some quarters today still. We believe those are backward looking fears. The large US banks have, on average, better balance sheets than a decade ago, meaning more conservative loan portfolios supported by more equity. Yet stricter underwriting by banks and a reduced willingness to lend created a credit void in the market.

Wall Street, always happy to create and sell products, stepped in to fill the gap with passive and active mutual funds, partnerships and various structured vehicles. The addition of debt to many of these portfolios allowed for the supply to meet escalating demand. It can be a match made in heaven or hell when an enthusiastic seller finds an agreeable buyer, and there have been plenty of those. Who doesn’t like (almost) free money?

Low base interest rates and a narrow spread to a risk-free rate has led companies to refinance and add new debt with a much lower hurdle rate, which allows for near-term accretive activities like M&A, share repurchases and so forth. But the longer term is something else entirely, as a company’s ability to satisfy its existing debt obligations may eventually be challenged by a recession due to weaker cash flow and more circumspect lenders who require a higher coupon rate to justify the perceived risk. And, of course, the base level of interest rates might not be so low as it has been.

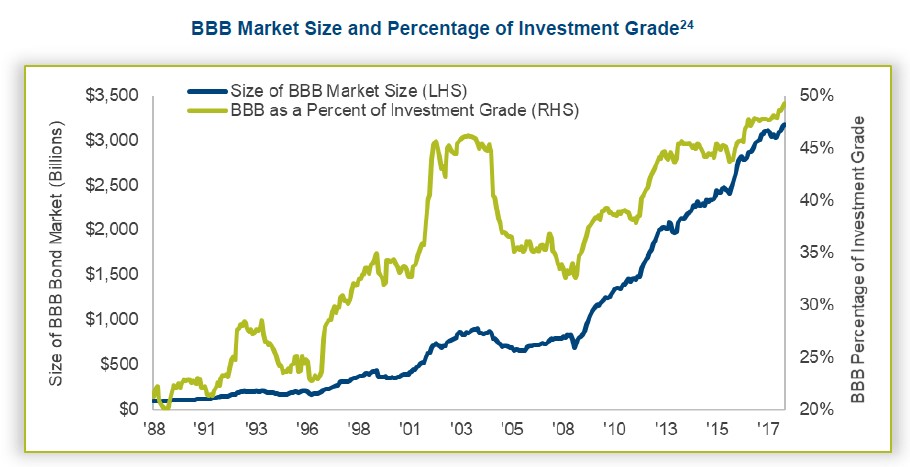

Corporate bonds can be segmented into two broad categories: High-yield and levered loans and investment grade. While, high-yield bonds and levered loans outstanding grew from $1.3 trillion to almost $2.4 trillion, the investment grade debt market almost tripled from $2.5 trillion to $6.4 trillion.16

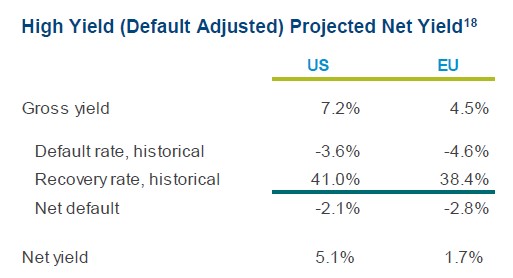

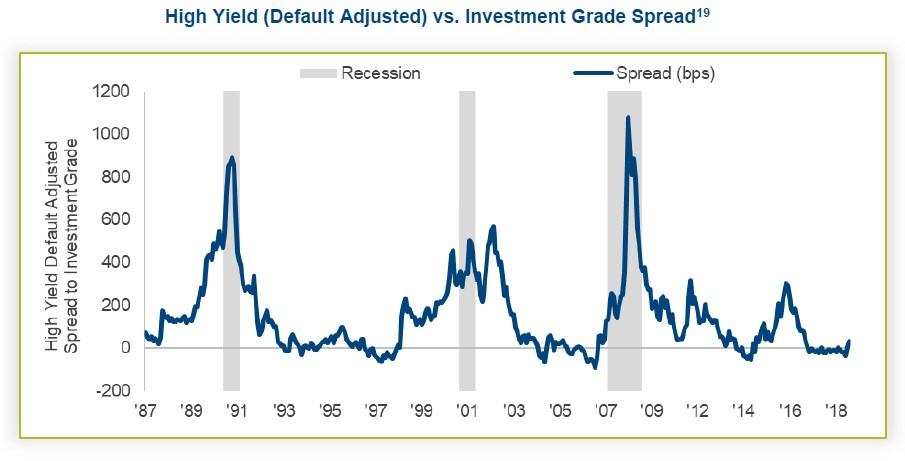

High-yield bonds, which are a reasonable proxy for levered loans, now offer a prospective return to maturity of just 7.2%.17 In our view, that’s still an unattractive yield for the risk assumed – and it’s a gross yield, before any defaults. If one were to consider the yield following some inevitable level of defaults, the net yield will be lower. We can debate what defaults will be, but defaults have not been, and most likely never will be, zero. Using historic default rates as a rough proxy for illustrative purposes, the net yield on US high-yield bonds drops dramatically, to just 5.1%. It stands to reason that the longest economic expansion in history has bred some degree of complacency among borrowers and lenders and that future defaults may climb above the average before too long.

US junk bond yields fall in line with investment grade bond yields, begging the question, Why bother?

The prospective net yield of high-yield European bonds is just 1.7%20, far lower than even that of US bonds. Such unjustifiably low yields are a function of a lower European base interest rate and the European Central Bank’s (ECB) market-manipulating purchase of slightly more than 20% of eligible corporate bonds in the last couple of years – €174 billion purchased of €850 billion eligible.21 We call this government-managed capitalism.

The US and EU are not alone. Other parts of the world also have their fair share of weak corporate credits, as pointed out in a 2018 McKinsey report.22

Economic cycles will not be subverted – despite the best efforts of central bankers – and there will again be defaults, quite possibly with a lower recovery in bankruptcy, with only the magnitude up for argument.

We strongly feel that the high-yield bond market’s net yield does not justify the risk. And we haven’t touched on the rise in leverage yet. Some might call that prospective yield “return free risk.”

The investment grade market generally holds up well in recession, but we suspect it will not fare as well this time around. The near trebling of investment grade debt masks the negative mix shift in the composition of that debt. In 2008, 32.6% of investment grade bonds were BBB, just one slim notch above junk. Today, about half of the investment grade universe is rated BBB. Investment grade debt has doubled, but the BBB tranche has nearly quadrupled – from $896 billion to almost $3.2 trillion! BBB-rated debt has never been so large, neither on a percentage basis nor in dollar terms.23 It has grown about 14% annually since 2008 and cannot continue to grow at such a rapid clip forever. Eventually, a recession will test ratings and solvency.

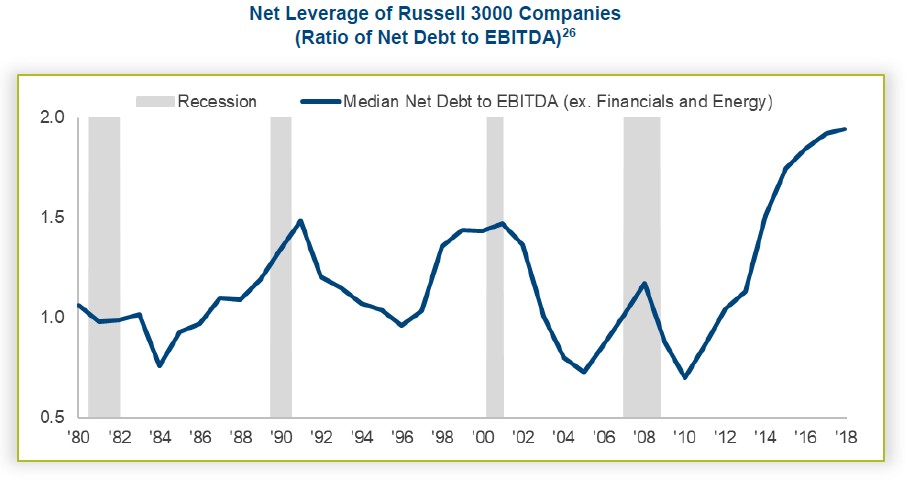

Credit metrics for corporate debt are already worse than typically observed in a recession, and we’re not even in a recession yet!

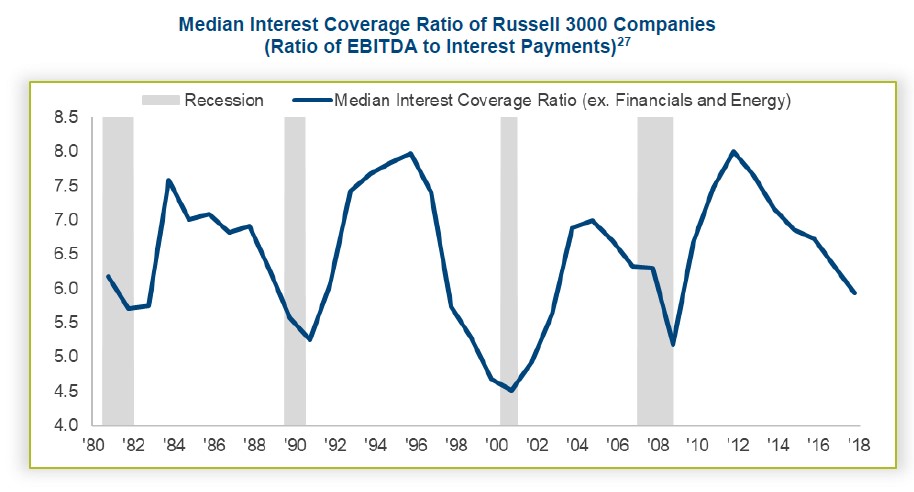

Net debt/EBITDA of the companies in the Russell 3000 index has never been this high for what is still a good economy.25 One should expect that net debt/EBITDA would increase in a recession, as it has in the past – a function of weaker denominator.

Rating agencies place less weight on debt levels today than they do on cash flow coverage of interest expense, but the commonly viewed measure of EBITDA/Interest Expense is uncharacteristically low for a non-recessionary period – a function of both higher debt levels and unusually low interest rates. A recession would only cause this ratio to deteriorate further.

We believe that the environment for corporate debt is worse than the previous two charts suggest. For one thing, EBITDA should not be confused with cash flow. A proper analysis requires the deduction of maintenance capital spending at the very least. We don’t know that number, but it is something greater than zero and therefore places the typical corporate bond more on the precipice than if EBITDA alone is considered.

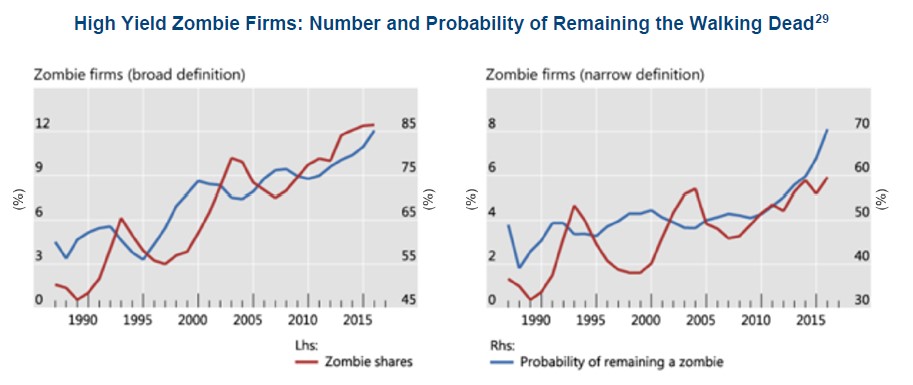

An unusually low base interest rate and historically tight spreads have combined to give borrowers a cost of funds so low that they do not face the existential risk of a more normal lending environment. This, in turn, begets the zombie company – a company that by all rights should be bankrupt yet finds itself able to remain solvent. Zombie firms are on the rise and surviving longer, as research in the recent BIS Quarterly Review shows.28

A zombie company is generally a mediocre business with a leveraged balance sheet that can avoid a restructuring, though for only so long. It can repay interest on its debts at its current borrowing rate but is unable to repay principal. Eventually, a catalyst will bring a day of reckoning that impedes a zombie’s ability to service its debt due to, say, a recession that negatively impacts its cash flow or a rise in the base rate and a larger premium to that base rate (in other words, a wider spread) that increases its borrowing cost.

Interest rates might rise as either a function of inflation or because buyers of US government debt go on a strike kicked off by trade wars or deficits or the fear that our regulators won’t make the tough decisions needed to protect our fiat currency. We do not handicap individual outcomes, but none are particularly good.

A blind faith in central bankers has yet to completely erode despite an inability to subjugate economic cycles. When the economy does weaken, financial pressure will finally render the walking dead inert. We believe lenders will inevitably become more vigilant – better late than never – and will demand higher yields for refinancing and new debt.

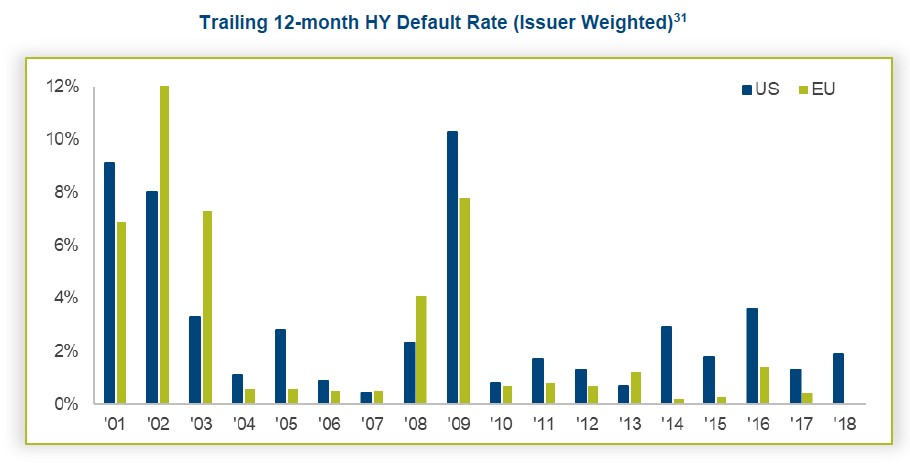

This likely will lead to higher levels of default than we have recently experienced. US default rates currently are just half the historic average, 1.8% vs 3.6% historic average30. As you can see in the following chart, defaults have been higher in the past.

Once a company defaults on its debt and enters bankruptcy, it goes through a restructuring where equity is generally wiped out and the lenders, banks and bondholders, fight over the carcass for some level of recovery. The level of recovery, like defaults, moves up and down in good and bad times.

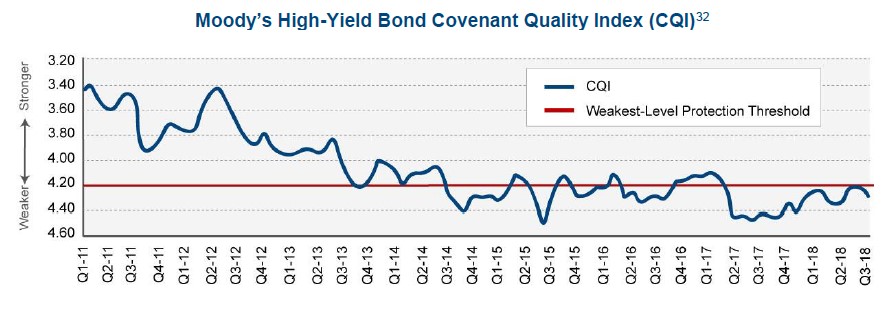

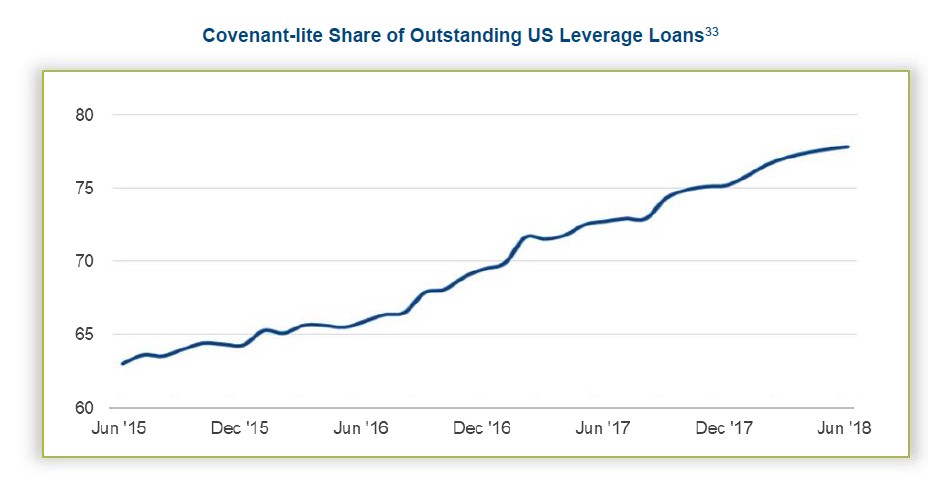

A benign investment environment has allowed many companies to issue debt with unprecedentedly advantageous terms that will support borrowers all the way into and through bankruptcy. These “covenant-lite” loans will likely have a negative impact on recoveries.

We wouldn’t therefore be surprised if future defaults and recoveries are worse than normal, particularly given the much larger amount of debt that exists today, which has produced more leveraged companies than we’ve historically seen at this point in the cycle, not to mention the complacency that has crescendoed during the longest equity bull market on record.

Most corporate bonds will, of course, not default. But we believe the impact will be felt broadly across the asset class nonetheless. Fear will likely cause corporate bond yields to rise, meaning prices will fall. Most corporate bonds will likely take a price hit, with the weakest credits with the longest duration being hit the hardest. High-yield bonds and levered loans will see some big negative marks, but investment grade debt will not be immune either. As we noted, investment grade product has about the poorest credit quality in its history, and a debt market like this one – $6.4 trillion with $3.2 trillion of it rated BBB, plus another $2.4 trillion in high-yield debt and levered loans – has never traversed an economic downturn.34

Although a recession might suggest lower rates, which would be a mitigating factor, we can construct scenarios where rates do not fall as expected. The potential for the aforementioned buyer’s strike against government bonds, for example, might cause rates to fall less than expected, if at all. This is not something we project but merely point out as a not unthinkable possibility.

When corporate bonds perform poorly, we would not be surprised to see mutual fund shareholders seek redemptions from less vigilant bond funds, which would cause those funds to start selling their corporate credits, which in turn would lead to further price declines, further underperformance, further redemptions, further bond sales, and so on in a not-so-virtuous circle. For the want of a nail the kingdom was lost.

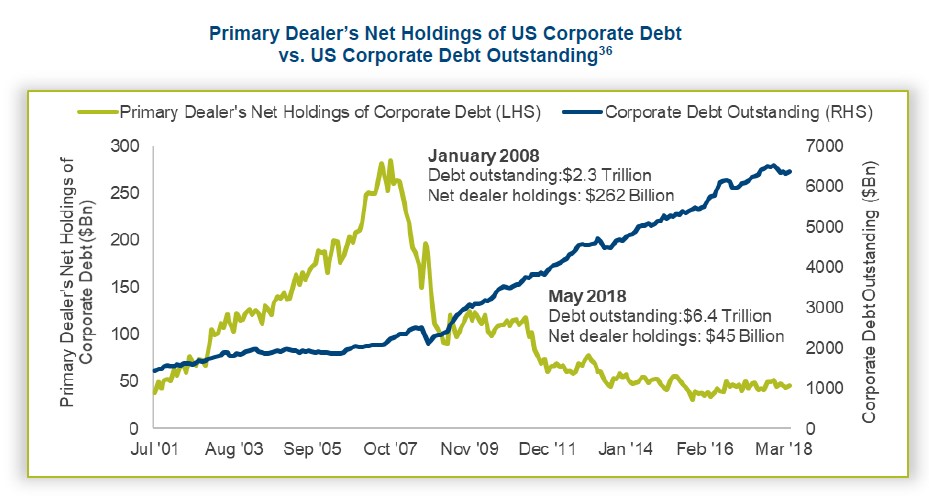

The largest corporate bond market in history will intensify this circle. The math is simple. A decade ago, if 10% of corporate bonds transacted, a new home would need to be found for roughly $450 billion of them, whereas today, a significantly larger home would be needed to accommodate $900 billion worth.

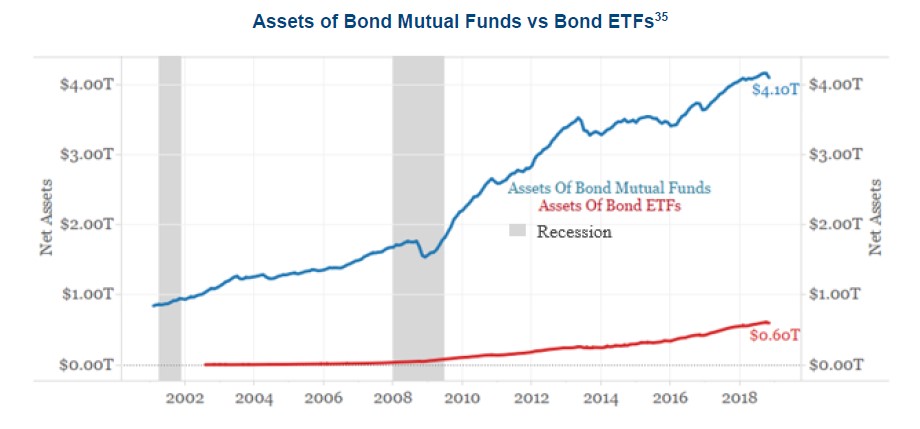

To date, the increase in supply of corporate bonds has partially been soaked up by the increase in corporate bond exchange traded funds (ETFs). Such passive funds have grown from an immaterial amount in 2008 to $600 billion today.

A relevant trait of most such funds is that they transact indiscriminately with frequent, ratable purchases and sales – a function of ETF inflows or outflows, respectively – that can drive bond prices to both new highs and new lows. In a downturn, passive investment vehicles could be forced to indiscriminately sell those investment grade bonds that the ratings agencies have downgraded to junk.

Given the huge size of the BBB market, downgrades could incite a large volume of selling that could then infiltrate the rest of the market and quite possibly exacerbate the negative price action.

There is no bond exchange, unlike the many exchanges for stocks, so matching buyers and sellers of bonds isn’t always an easy task. Trading desks of investment banks used to facilitate markets by assuming risk and holding bonds on their balance sheets. Such market making represented about 10% of the overall corporate bond market a decade ago, but today, trading desks hold less than 1% of total corporate bonds in inventory.

More corporate bonds, more corporate bonds in passive hands, and less help from trading desks to smooth buying and selling of corporate bonds could well lead to price declines larger than one might otherwise suspect.

The proliferation of corporate credit filled the lending void left by the banks after the last recession. More corporate loans with a higher level of leverage, however, leave us with an elevated risk of default.

Current holders of corporate debt typically operate with less leverage and are less integral to the daily exchange of money than the banks, factors that will mitigate the impact of higher defaults on the financial system as a whole. Nevertheless, many unwary bondholders may be harmed, and the spillover effects – higher costs and tighter availability of credit, among other things – are likely to dent the broader economy.

Now we have defined the challenges facing the corporate bond market here in the US and abroad. That does not prescribe any one particular path, but we see no reason to be buyers of any size today. We are not getting paid to play. At FPA, our habit is to respond to price. The market offers a selling price, and we decide if we like that offer.

Our concerns regarding today’s environment lead our Contrarian Value (CV) and Fixed Income (FI) teams to await better opportunities in both investment grade and high-yield bonds and levered loans, buying only when the risk assumed is appropriately offset by the prospective reward.

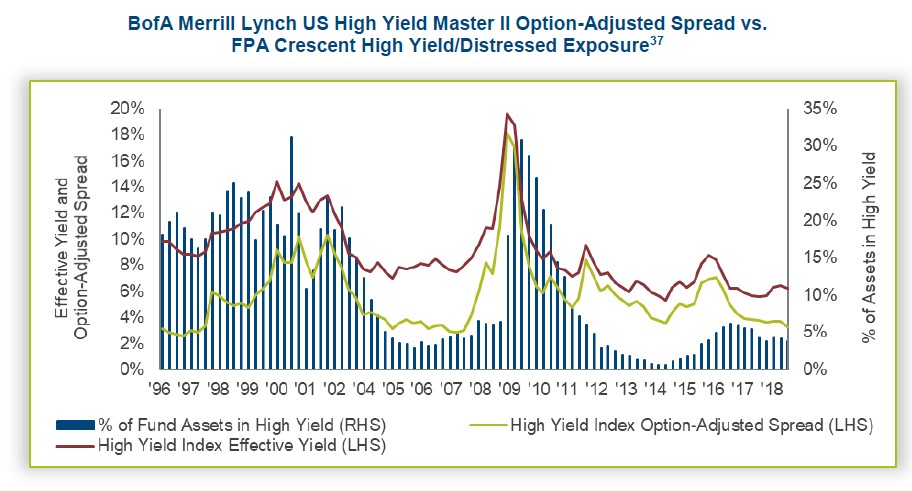

The CV team, which also manages the FPA Crescent Fund, considers high-yield debt and levered loans a vital part of the portfolio. Yet the fund currently has negligible exposure to that asset class, in contrast to its historic allocation, which at one point stood in excess of 30% of the portfolio. As the following chart shows, the team makes investments (the blue bar) in the asset class when there is an attractive combination of yield and spread (the red and green lines). For all of the aforementioned reasons, the strategy’s current exposure is low, but we expect future opportunities.

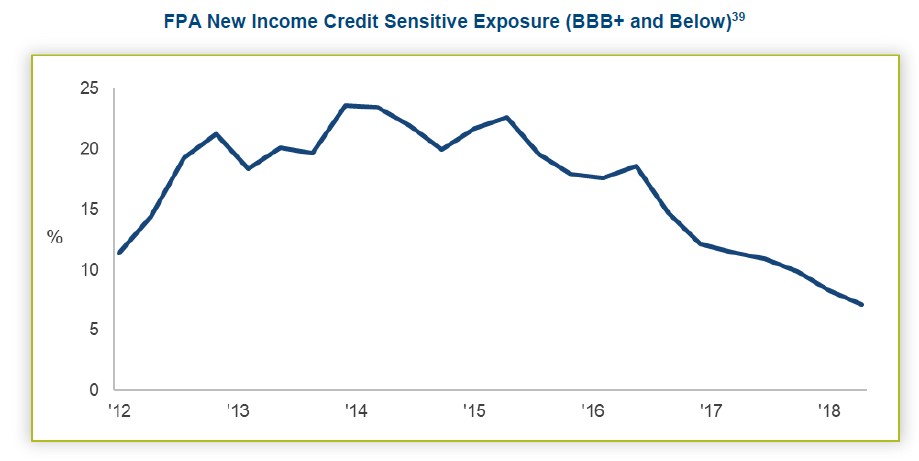

The FI team, which also manages the FPA New Income, Inc. fund, similarly seeks opportunistic buys of levered loans and high yield and also believes that this corporate debt market offers little by way of margin of safety. This explains the FI team’s reduced exposure, with approximately 1% of FPA New Income in investment grade corporate debt38 – and even that exposure has a below market term maintaining an average maturity of less than two years. As absolute return investors, owning long-dated investment grade bonds at low single-digit yields makes little sense, and we therefore patiently await cheaper prices, otherwise known as higher yields.

Some choose to live in zones at high risk of fires and volcanic eruptions without understanding the risk, while others understand the risk yet live there anyway. We believe many investors in the bond market are living with risk they don’t appreciate and so lack appropriate consideration for what might happen. At some point, fear will reenter the market, and both FPA teams are prepared to follow on its heels to scoop up attractive opportunities.

The thoughts communicated today are not new, but given the continued stretching of the proverbial rubber band, we thought it prudent to spend this time communicating our concern. Fears of a recession have led to corporate bond market weakness in Q4 2018, and with the commensurate increase in lender caution, we are beginning to see investment grade borrowing costs increase. We cannot and never do speak to timing. This may all be a head fake at this moment in time. That, however, does not change the real risk that remains – a risk that someday may be realized.

Michael Lewis discusses unappreciated threats in his new book, The Fifth Risk. Although he isn’t speaking of investing, one of his thoughts seems a fitting way to close. “If your ambition is to maximize short-term gain without regard to the long-term cost, you are better off not knowing the cost.” On the contrary, we seek to maximize long-term gain while knowing the costs, willing as always to sacrifice the near-term in its pursuit.

Respectfully,

Steven Romick, Abhijeet Patwardhan, Thomas Atteberry