“We have repeatedly commented on the increasing complexity of Burford’s investment transactions, and the Jaguar investment is an example of both investment and accounting complexity – but also an illustration of our success in turning complexity into profit.”1

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

(Readers of this report will likely come to view this statement as stunningly brazen.)

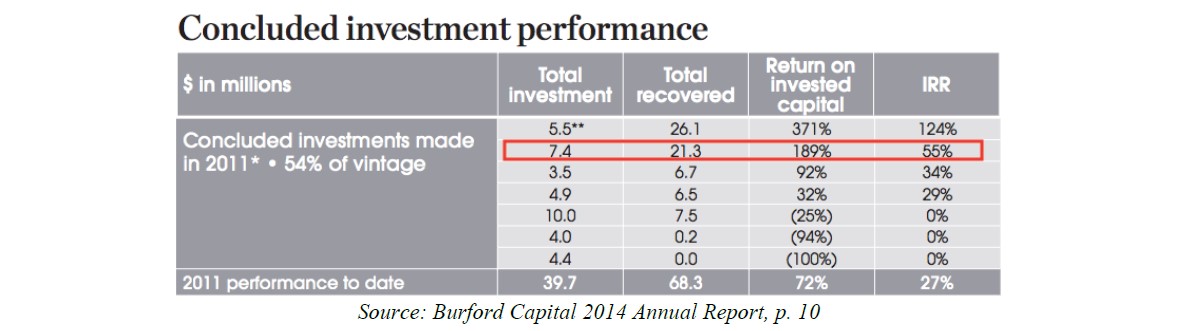

Introduction

We are short Burford Capital Limited (LON:BUR). For years, it was the ultimate “trust me” stock. Thanks to a light disclosure regime, the esoteric nature of its business, and unethical behavior by its largest shareholder, Invesco, it turned Enron-esque mark-to-model accounting into the biggest stock promotion on the AIM. This has all recently changed though. Just this year, BUR began publishing more detailed investment data. This data proves that BUR has been egregiously misrepresenting its ROIC and IRRs, as well as the state of its overall business.

BUR’s top management, through their shareholdings (and sales), is in effect primarily compensated for aggressively marking cases in order to generate non-cash fair value gains. We calculate that as of H1 2019, fair value gains constituted 53.9% of balance sheet core litigation assets (up from 47.4% as of December 31, 2018). Until now, BUR has gotten away with aggressive and unwarranted marks by touting ROIC and IRR metrics. We show that BUR heavily manipulates these metrics. BUR then actively misleads investors about how its accounting for realized gains works. As a result of this deception, we believe investors give credence to BUR’s fair value gains. We believe that at least 72% – and possibly as much as 90% – of H1 2019 Total Investment Income was really from Fair Value Gains. (BUR’s Investment Income shows Fair Value Movements were 55.1% of Total Investment Income during the period.)

In actuality, BUR’s net realized returns have relied on a very small number of cases. Just four cases have produced approximately 66% of BUR’s net realized gains during 2012 through H1 2019. We calculate that the other concluded cases during this time generated a combined ROIC of only approximately 19%. (One of the four outsized contributors was actually a loss a trial, and was bailed out by BUR’s largest shareholder, Invesco, at the direction of Neil Woodford protégé Mark Barnett. Absent the bailout, the case almost certainly would have been a total loss.) The reality of BUR’s dependence on a small number of cases for the bulk of its returns is in stark contrast to the impression many investors seem to have that the portfolio produces meaningful returns across its breadth.

BUR’s liquidity is risky, and it is arguably insolvent. We believe that BUR’s “real” invested capital is $880.3 million. BUR’s massive operating expenses tax that at approximately 9%, based on LTM expenses. BUR’s financing costs (including dividends) add another 8.3%. Therefore, in our opinion, the first approximately 16.5% of returns BUR’s adjusted investment capital generates goes to keeping the lights on. BUR is arguably insolvent, as its debt and funding commitments greatly exceed the $880.3 million adjusted invested capital.

BUR is a perfect storm for an accounting fiasco. It is a fund that invests in an illiquid and esoteric asset class, which few investors can understand well. By remaining listed on AIM despite being a midcap company, the company’s disclosure requirements are lighter than they would be for the main board – and far lighter than they should be. By choosing to account for its litigation investments as financial assets, BUR utilizes fair value accounting for a balance sheet largely comprised of Level 3 fair value assets (i.e., “mark to model” accounting of Enron fame). BUR disingenuously blames IFRS for needing to take (outsized) fair value gains when in fact, it was BUR’s choice to adopt this accounting.

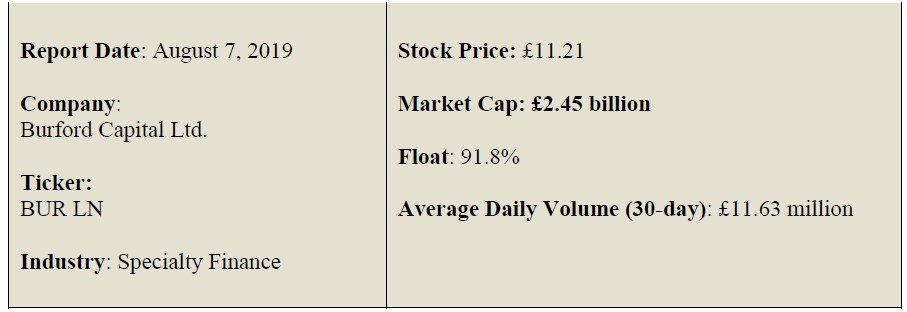

BUR’s governance strictures are laughter-inducing. The CFO is the wife of the founder / CEO. Under the best of circumstances, this should alarm investors; however, with a company that consistently books non-cash accounting profits, it is unforgivable. In a situation so ripe for abuse, the very least the company could do is to have an independent CFO. (The CEO has sold a total of £59.4 million of stock.) BUR has cycled through four prior CFOs or senior finance managers (none of whom stayed for long). The table below shows the turnover at CFO and senior finance functions. These facts beg the question “Is Elizabeth O’Connell the only CFO who can be relied upon to approve the accounts?”

The directors have each served on the board approximately 10 years, and per the UK Corporate Governance code, are no longer considered independent. (In a bizarre defense of worst practices, BUR recently pointed out that it is not subject to the governance code, and thus sees no need to change the board.2) After spending $160 million to buy a litigation fund management business, Gerchen Keller, and entering into employment and non-compete agreements with its principals, those principals left to start a law firm that focuses on taking cases on contingency.3 We cannot help but feel that BUR had ulterior motives for this acquisition, such as to consolidate assets in order to make its debt load look less ominous, or to ensure it is valued as an operating business, rather than as a closed-end fund. BUR has issued $646.9 million of retail bonds, and yet has no credit ratings.

Summary

We are short BUR because it is a poor business masquerading as a great one. BUR woos investors with non-IFRS metrics, particularly IRR and ROIC.4,5,6 However, these metrics are meaningless. They are heavily manipulated and greatly mislead investors about BUR’s actual returns. We have identified seven techniques through which BUR manipulates its metrics to create what we believe is an egregiously misleading picture of its investment returns. These manipulations usually involve BUR either giving itself credit for a recovery when one is uncertain (or even highly unlikely) or ignoring cases that are likely to be failures. The manipulation techniques are: 1) categorizing a loss as a win, 2) counting as “recoveries” awards or settlements with uncertain to highly unlikely collections as equivalent to cash returns when calculating IRR, 3) misleadingly representing investments that BUR inherited from acquisitions as favorable IRR, 4) choosing its own cost denominator in a case with a recovery when the total cost is much greater, 5) delaying recognizing a trial loss for two years, 6) keeping trial losses out of the “Concluded Investment” category, and 7) failing to deduct various costs against recoveries, including the very operating expenses associated with the investments themselves.

It is only since BUR finally provided an investment data table in H1 2019 on its website that it has now become possible to analyze individual cases and understand how misleading BUR’s presentation of returns is. Through analyzing these cases, we were able to identify these various manipulation techniques.

BUR also reinforces the misperceptions that its fair value gains are prudent by very cleverly conflating two distinct concepts: Realized Gains and Net Realized Gains. BUR’s total investment income generally shows a roughly 50/50 split between Net Realized Gains and Fair Value Movements. Net Realized Gains actually include previously recognized Fair Value Gains. In other words, a Net Realized Gain is Proceeds minus BUR’s invested capital in the case – not minus the investment’s Carrying Value. We think the vast majority of investors believes the opposite is true – that Net Realized Gains are Proceeds minus the Carrying Values.7 To the extent we are correct that most investors misunderstand Net Realized Gains, it is because BUR deliberately misled them.

In reality, significant Net Realized Gains do not imply that BUR’s Fair Value Gains are in fact conservative. Even more problematic is that when BUR books a Net Realized Gain that includes a previously booked Fair Value Gain, to balance out the accounts, an amount equal to the previously booked Fair Value Gain is deducted from the current period’s Fair Value Movements.

BUR has been highly reliant on only four cases for its monetizations, showing that its broader portfolio has lacked strength. Through manipulating ROICs and IRRs, BUR portrays itself as a business that derives profits from a broad range of cases in its book. The reality is that BUR’s profits are much more concentrated, and have really been dependent on just four cases that have generated approximately two-thirds of its net realized gains since 2012. We calculate that during this time, the remainder of the Concluded Investments generated a combined ROIC of only approximately 19%.

BUR appears financially fragile. BUR’s operating expenses, financing costs, debt, and funding commitments, in our view, put it at high risk of a liquidity crunch. BUR is already arguably insolvent. We believe BUR’s “real” invested capital is $880.3 million. In our view, this adjusted capital needs to generate returns that fund operating expenses equal to approximately 9% of its balance, along with another approximately 7.5% of financing expenses. We believe that these cash needs are why BUR frequently raises capital. BUR’s debt and litigation commitments together dwarf this adjusted capital base, meaning BUR could be viewed as insolvent.

Manipulation of Performance Metrics

By analyzing individual cases, we identified seven techniques that BUR has used to manipulate its performance metrics. Those methods are: 1) Categorizing a loss as an investment with a significant return, 2) counting as “recoveries” awards or settlements with uncertain to highly unlikely collections as equivalent to cash returns when calculating IRR, 3) representing an investment that BUR inherited when it acquired GKC in a way that misleadingly significantly boosted claimed returns, 4) choosing its own cost denominator in a case with a recovery when the total cost is much greater, 5) delaying recognizing a trial loss for two years, 6) keeping losses out of the “Concluded Investment” category, and 7) failing to deduct the costs of making and maintaining litigation investments against associated recoveries, which are approximately 9% on a LTM basis of BUR’s adjusted invested capital.

#1 Categorizing a Loss as an Investment with Significant Return

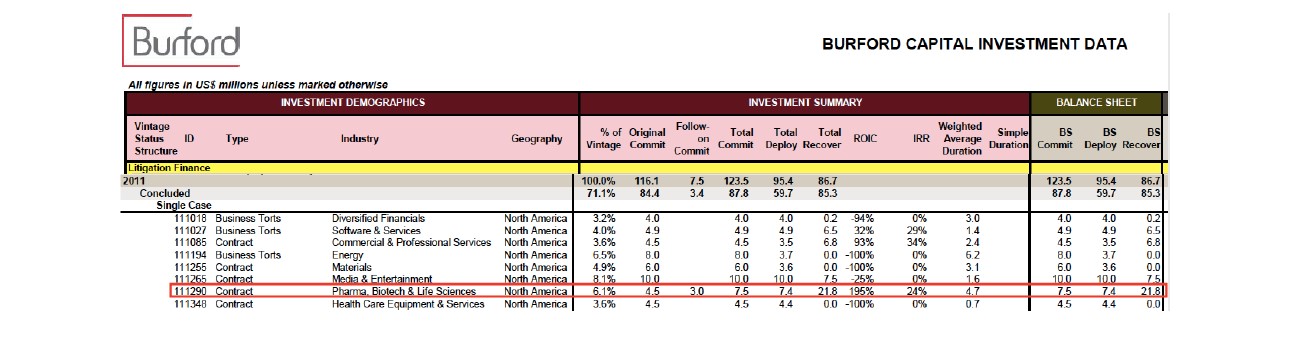

BUR’s reporting of Napo Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Salix Pharmaceuticals Inc. (“Napo”, BUR case no. 111290) should make BUR investors want to take a shower.8 (This is the case referenced in the quote about ‘Jaguar’ at the beginning of this report.) The simplest problem is that BUR actually categorized it as a Concluded Investment in 2013. However, the case did not reach a verdict until 2014. BUR’s 2013 annual report showed the case generated a positive ROIC of over 100%, but the 2014 verdict was a complete loss for BUR’s client, Napo. These events were just the tip of the iceberg however. BUR’s largest shareholder helped lead a bailout of the investment, which led to BUR preserving – and then actually increasing – this illusory return. (BUR finally trued up Napo around the time it issued its H1 2019 interim report.)

Napo is a stranger-than-fiction example of manipulating performance and profit metrics. Not only do we view BUR’s management as having acted highly unethically in this instance, but we also see Invesco fund manager Mark Barnett as having been equally complicit in ways reminiscent of some of the highly aggressive marking value techniques he and Neil Woodford have employed together.9 (Mr. Woodford’s fund was the second-largest shareholder in BUR, next to Invesco, and Mr. Woodford is responsible for Invesco’s initial investment in BUR.10) Through accounting sleight of hand, a cash investment partially provided by Invesco, and a reverse merger into a soon-to-collapse U.S. nanocap led by a highly questionable CEO, BUR turned a loss at trial into a purported 195% ROIC.

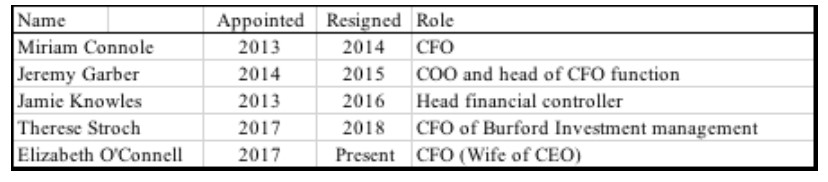

BUR first disclosed Napo as a “Concluded Investment” in its 2013 Annual Report, and claimed a total recovered of $15.8 million on a $7.4 million investment, which was purportedly a 113% ROIC.11 However, the case had not yet concluded. It reached a jury verdict in 2014, and BUR’s client, Napo, actually lost the trial when the jury returned a verdict in favor of Salix.12 In the 2013 disclosure, Napo was shown as the largest recovery from the 2011 vintage, which BUR calculated had generated a ROIC of 53%. Without the bailout of this case, BUR’s 2011 Concluded Investment ROIC would have been only 2.9%. Given BUR’s claim that litigation typically takes one to two years to generate returns, showing a 53% ROIC from the 2011 vintage must have helped to woo investors.

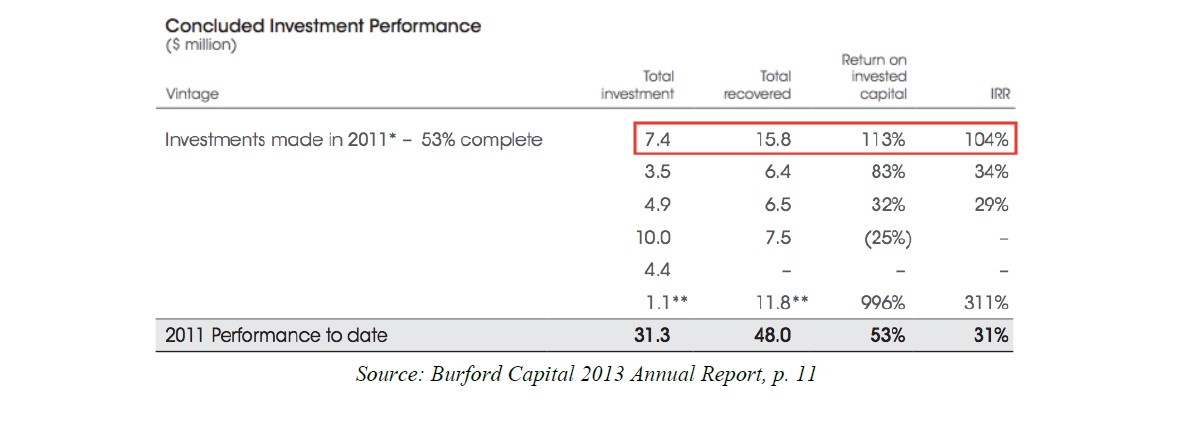

The fact that Napo actually lost the trial in 2014 did not sour the company’s view of its investment. Rather than reverse the gain, BUR actually marked the investment up yet again – to a ROIC of 189%.

BUR apparently converted its investment into a debt of Napo totaling $30 million as of October 10, 2014. It appears that Napo was separately indebted to law firm Boies Schiller as well as several investment firm creditors.13 The BUR debt was not repaid, and Napo and BUR’s subsidiary, Nantucket Investments Ltd., entered into a debt forbearance agreement in December 2016 for what was then marked as a $52.8 million debt (including $729,000 of accrued interest).14 Concurrent with the forbearance agreement, Napo took on additional debt from another fund that became senior to Burford’s.15 Napo appears to have been headed to bankruptcy, because as of December 31, 2016, it had $391,000 LTM revenue, an operating loss of -$4.1 million, cash of only $2.3 million, debt of $58.9 million, and a negative book value of – $58.9 million.

BUR’s litigation investment needed a bailout by this time. Enter BUR’s largest shareholder, Invesco, and its Invesco Perpetual Income and Growth Investment Trust plc and Invesco UK Strategic Income Fund, both managed by Mark Barnett.16,17 Another Invesco fund, also managed by Mr. Barnett, the Invesco High Income Fund (f/k/a the Invesco Perpetual High Income Fund), is the largest shareholder of BUR.18

By getting involved with Napo and Jaguar, both Invesco and BUR had gone decidedly low rent. Napo was started by a Silicon Valley entrepreneur with a checkered history, Lisa Conte. For over a decade, Ms. Conte ran a company called Shaman Pharmaceuticals. Shaman initially promised cures for cancer and HIV before filing for bankruptcy in 1999.19 Ms. Conte then started a dietary supplements company from the ashes of Shaman and, when that business failed, founded Napo in 2001.20 In 2010, she told Forbes that she had burned through $200 million of funding in her quest to make pharmaceuticals from rainforest medicines.21 When Napo entered into the forbearance agreement with BUR, the plan was to merge Napo into another Contefounded U.S.-listed entity, Jaguar Animal Health Inc.22 The merger was completed July 31, 2017.23

The merger plan required Napo to pay BUR $8 million cash, and issue approximately 43 million Jaguar shares “as a compromise” to settle Napo’s loan obligation.24,25 The cash came from an equity raise Jaguar completed with the merger.26 The Invesco Perpetual Income and Growth Investment Trust plc or Invesco UK Strategic Income Fund backstopped the financing, subscribing for 3,243,243 Jaguar shares for $3 million. All $3 million went “immediately” from the fund to BUR’s subsidiary Nantucket. According to the Joint Merger Proxy Statement / Prospectus, the direct payment to Nantucket / BUR was an express condition of Invesco’s investment.27,28 Interestingly, Nantucket’s address of record is listed as that of Invesco’s global headquarters on Jaguar Health’s 2017 proxy statement.29

We are unsure how the investment in Jaguar comported with the Invesco Perpetual Income and Growth Investment Trust plc’s objective, which was “to provide shareholders with capital growth and real growth in dividends over the medium to long term from a portfolio of securities listed mainly in the UK equity market.”30 Given that one of Mr. Barnett’s other funds was the largest shareholder of BUR, we assume this investment was made purely to perpetuate a mythical ROIC and IRR.

Regardless, this $8 million repaid the $7.4 million that BUR had invested, making the cash-on-cash ROIC approximately only 8.1%.31 But while the cash-on-cash returns were anemic, there was still the value of the Jaguar shares that BUR received. For a minute anyway:

As shown above, the highest Jaguar’s stock has traded since the merger was the day immediately following it. By the end of 2017, Jaguar had declined 76.2% from August 1, 2017. BUR, which was restricted from selling the vast majority of the shares and had unrealized losses on the stock of $6.95 million by the end of 2017, took yet another markup on Napo to a ROIC of 195%.32,33 Rather than writing down the recovery from the case, BUR reported the loss as a “net loss on equity securities”, making it highly likely that few – if any – investors ever became aware that the reported ROIC and IRR of Napo was a sham.34

BUR was able to sell very little of its share grant. Over 40% of the shares issued were subject to a minimum share price condition, which fast-declining Jaguar stock tripped before the ink had even dried on the merger.35 Another 45%+ of the shares were to be held in escrow for three years subject to certain conditions.36 Both equity tranches are now basically worthless.

What remainder BUR could dispose of, it did, netting ~$600,000 in September 2018.37 This sum was, however, a far cry from the payouts of up to $45 million that had been discussed in the company’s agreement with Jaguar a year and a half earlier.38 At some point after April 2019 – seven years after the litigation funding, BUR finally trued up Napo in the Concluded investment table. Without any fanfare or announcement, the table now shows a ROIC of 18% and an IRR of 3%.39 With Jaguar’s entire market cap sitting at $5 million and having had its equity diluted four separate times, BUR finally decided to reduce its recovery for the matter, explaining that “the stock has underperformed and we have concluded we would not be able to sell it for much”.40

Without the Invesco-led bailout, Napo likely would have been a total loss. We believe BUR investors have been bamboozled by the company and Invesco.

#2 Counting as “Recoveries” Awards or Settlements with Uncertain to Highly Unlikely Collections as Equivalent to Cash Returns when Calculating IRR

BUR’s IRR calculation, which is a significant factor underpinning investors’ enthusiasm for the stock, depends on three factors: The amount recovered, the amount deployed, and the timing of recovery. In this report, we challenge the amounts recovered and deployed (in terms of what BUR includes in its Concluded Investments); however, we see that BUR has misleadingly boosted its IRR numbers by deeming amounts recovered when in reality they were years away from collection. BUR has also deemed patents that it subjectively valued as recovered amounts, which unsurprisingly, resulted in a downside reassessment after deeming the case concluded.

BUR showed a counterclaim from Desert Ridge Community Association, et al. v. City of Phoenix, et al. (“Desert Ridge”) as a Concluded Investment in its 2013 annual report.41 The problem is that BUR showed an IRR of 51% as of 2013.42,43 However, payment was contingent upon BUR’s client, counterclaimant Gray Development, selling off a parcel of real estate. In 2016, with the land unsold, BUR sold the promissory note entitling BUR to its portion of the potential proceeds at a steep discount. The new buyer, a rival real estate developer, foreclosed on the property and plunged Gray into bankruptcy.44

As a result of BUR’s actions years after the conclusion of the investment, Gray’s bankruptcy estate is now suing BUR for violating its “duties of good faith and fair dealing”, alleging the note sale sent a signal to the market that Gray was not able to find a buyer for the property.45 BUR has adjusted down IRRs on Desert Ridge to 47% today.46 However, BUR has not acknowledged the significant contingent liability that accompanies this lawsuit, in which Gray’s bankruptcy estate claims more than $200 million in damages. Final recoveries remain uncertain more than six years after Desert Ridge was concluded.

In a separate case, in H1 2019 (case 122094), BUR disclosed a perplexing scenario in which it had received as proceeds certain intellectual property “that was dependent on the inventor’s continuing activities”.47 The inventor died, and according to BUR, it had to write down the recovery in the associated case by $3 million. Whether this tragic event was foreseeable or not is impossible to gauge, but the fact that BUR received a non-cash recovery with a subjective valuation does not inspire confidence in the caliber of said “recoveries”.

Read the full article by Muddy Waters