When Howard Schultz opened his first coffee store in Seattle, he strove to replicate the experience of the coffee houses he’d visited in Italy; a place where people would come to meet, in a place that encompassed a welcoming and engaging atmosphere. Starbucks wasn’t to be just about selling a good cup of coffee, in fact it was to be an experience, and it was all about people.

From the beginning, Starbucks took extra care of their staff, which elicited the power of reciprocation and fostered a bond between Starbucks’ employees and their customers. A friendly culture developed which drove repeat business and provided a competitive advantage. A focus on customer experience ensured the stores offered a unique and inviting social gathering place for the communities they served, and a long runway for store roll-outs propelled the company’s earnings and share price.

While Starbucks’ beginning was all about people, over time, unfortunately, it became all about the numbers. Numbers, numbers, numbers. A history of double digit earnings growth allowed the company to neglect it’s cost base, all while setting the bar higher for even more growth. And naturally, management and Wall Street obliged.

As a result, a major impetus was placed on growth metrics like new store openings and comp sales. New product offerings unrelated to coffee and inferior store locations drove short term growth all while hurting the brand and the business.

And unfortunately, this is more common an occurrence than you might think.

For more than 25 years, Jim Collins has studied what makes great companies tick. In a recent Farnam Street podcast, he articulated that ‘over-reaching’ and ‘the undisciplined pursuit of more’ was responsible for the downfall of many great companies.

“Almost none of the companies we studied that were great companies that fell, fell because of complacency. They fell because of overreaching, the undisciplined pursuit of more. They became too aggressive, too much growth, firing un-calibrated cannonballs, expanding into areas of which they have no business operating. There’s a certain animus that happens, if we’ve been really successful. Now we just need to have more, and we need to be bigger.” Jim Collins

Once the Financial Crisis hit, Starbucks’ once unstoppable growth reversed. Declining consumer spending laid bare the misjudgments, cost blow-outs and inefficiencies of the business. Starbucks was broken.

It was then that Starbucks’ founder, Howard Schultz, returned to the role of ceo to rectify the company’s woes. While there was no silver bullet, there were many things the company needed to do to return to its core. The retail industry has witnessed very few successful turnarounds, but Starbucks is one. And the book, ‘Onward’, by Mr. Schultz, tells that story.

It’s a tale about how a business came to lose its way, about hubris and the dangers successful businesses face. It’s also a guide for getting back to your core, staying true to your values and innovating for the future. The book distills the essence of Starbucks success through its unique competitive advantages.

I’ve collected some of my favourite extracts below. Once again, you’ll notice many common threads with the other great businesses we’ve covered.

- Remove Hierarchy

- Win-Win

- Value Employees

- Value Customers

- Owner Mentality

- Misguided Focus on Growth

- Losing Focus

- Maintain Smallness

- Simple Model

- Love

- Mistakes

- Product

- Values

- Tone from the Top

- Innovation

- Culture

- Brand

- Marketing

- Reinvigorating the Brand

- No Silver Bullet

- Hubris

- Visit Stores

- Seek Feedback

- Change

- Difficult Choices

- Know the Customer

- Humility

- Competitive Advantage

- Costs

- Summary

Remove Hierarchy

“Since Starbuck’s earliest days, we have lower-cased all job titles.”

Win-Win

“As a business leader, my quest has never been just about winning or making money; it has also been about building a great, enduring company, which has always meant trying to strike a balance between profit and social conscience.”

“No business can do well for its shareholders without first doing well by all the people its business touches. For us, that means doing our best to treat everyone with respect and dignity, from coffee farmers and baristas to customers and neighbours.”

Value Employees

“We were the first US company to offer both comprehensive healthcare coverage as well as equity in the form of stock options to part-time workers, and we were routinely heralded as a great place to work.”

“Even as we lost money in the early years, Starbucks established two partner benefits that, at the time, were unique: full health-care benefits and equity in the form of stock options for every employee. This was an anomaly.”

“Acting with this level of benevolence helped us build trust with our people and, as a result, long-term value for our shareholders.”

“Owning a piece of the company gave so many of our partners a tremendous sense of pride, demonstrating that we respected our people enough to share our success.”

“Work should be personal. For all of us. Not just for the artist and the entrepreneur. Work should have meaning for the accountant, the construction worker, the technologist, the manager and the clerk.”

“Perhaps the most important step in improving the faltering US business was to re-engage our partners, especially those on the front lines: our baristas and store managers. They are the true ambassadors of our brand, the real merchants of romance and theatre, and as such the primary catalysts for delighting customers.”

“Our turnover rates in stores were too high, and a new generation of baristas had not been effectively trained or inspired by Starbucks’ mission.”

“Our compensation and benefits plans, while generous compared to almost any other retailer, no longer rang revolutionary.”

“Many baristas pen personal notes – ‘Christina rocks!’ – on cups of morning coffee. Our partners’ attitude and actions have such great potential to make our customers feel something. Delighted maybe. Or tickled. Special. Grateful. Connected. Yet the only reason our partners can make our customers feel good is because of how our partners feel about the company. Proud. Inspired. Appreciated. Cared for. Respected. Connected.”

“Franchising would have given us a war chest of cash and significantly increased our return on capital. But if Starbucks ceded ownership of stores to hundreds of individuals, it would be harder for us to maintain the fundamental trust our store partners had in the company, which, in turn, fueled the trust and connection they established with customers. Franchising worked well for other organisations, but would, I believe, create a very different organisation by diluting our unique culture.”

“People will always be our most important asset and Starbucks’ competitive advantage.”

Value Customers

“One of the most important pieces of advice I’d heard upon my return came from a dear Seattle friend and one of the country’s best retail executives, Jim Sinegal, the co founder and CEO of Costco Wholesale Corporation. ‘Protect and preserve your core customers’ he told our marketing team when I invited him to speak to us. ‘The cost of losing your core customers and trying to get them back during a down economy will be much greater than the cost of investing in them and trying to keep them’.”

Owner Mentality

“Part of the problem was that we did not have the proper incentives or the right in-store technology to help store managers operate like owners, taking more control of their stores’ destiny.”

“Knowledge can breed passion. Our company had to do a much better job sharing our coffee knowledge and communicating our mission. Pride in purpose would help give our partners a sense of ownership.”

“Starbucks’ best store managers are coaches, bosses, marketers, entrepreneurs, accountants, community ambassadors, and merchants all at once. The best managers take their jobs personally, treating the store as if it is their very own.”

Misguided Focus on Growth

“By 2007 Starbucks had begun to fail itself. Obsessed with growth, we took our eye off operations and became distracted from the core of our business. The damage was slow and quiet, incremental, like a single loose thread that unravels a sweater inch by inch.”

“We continued to set high bars for ourselves that Wall Street held us to, and every quarter, our people felt more intense pressure to maintain annual revenue and profit increases of at least 20 percent. It was an ambitious, some said unattainable goal that I was admittedly complicit in actively promoting.”

“We had trapped ourselves in a vicious cycle, one that celebrated the velocity of sales instead of what we were selling. We were opening as many as six stores each day, and every quarter our people were under intense pressure from Wall Street – and from within the company – to exceed past performance by showing increased comparative store sales, or comps.”

“We were so intent on building more stores fast to meet each quarter’s projected sales growth that, too often, we picked bad locations or didn’t adequately train newly hired baristas.”

“I liked to say that a partner’s job at Starbucks was to ‘deliver on the unexpected’ for customers. Now, many partners energies seemed to be focused on trying to deliver the expected, mostly for Wall Street.”

“[We needed to] refocus the company on customers instead of breakneck growth.”

“As I saw it, Starbucks had three primary constituencies: partners, customers, and shareholders, in that order, which is not to say that investors are third in order of importance. But to achieve long-term value for shareholders, a company must, in my view, first create value for its employees as well as its customers. Unfortunately, Wall Street does not always see it the same way and too often treats long-term investments as short-term dilution, bringing down the company’s value. Adopting this mentality was, in large part, how Starbucks had become complicit with the Street… We chased the pace of growth by building stores as fast as we could rather than investing in sustainable growth opportunities. The top line grew fast, but in a way that, for a variety of reasons was impossible to sustain.”

“Starbucks had been acting out of fear, mainly a fear of failure. So much of what the company had done was defensive, done to protect itself. Our primary goal had been to avoid missing our earnings projections rather to actively engage our customers.”

“Starbucks, I said, would no longer report its same store sales. Our comps would no longer be made public.”

“There was an even more important reason that I chose to eliminate comps from our quarterly reporting. They were a dangerous enemy in the battle to transform the company. We’d had almost 200 straight months of positive comps, unheard of momentum in retail. And as we grew faster and faster clip during 2006 and 2007 maintaining that positive comp growth history drove poor business decisions that veered us away from our core.”

“The fruits of this ‘comp effect’ could be seen in seemingly small details. Once, I walked into a store and was appalled by a proliferation of stuffed animals for sale. ‘What is this?’ I asked the store manager in frustration, pointing to a pile of wide-eyed cuddly toys that had absolutely nothing to do with coffee. The manager didn’t blink. ‘They’re great for incremental sales and have a big gross margin.’ This was the type of mentality that had become pervasive. And dangerous.'”

“Eliminating comps from the radar was my attempt to send a message to Starbucks partners; We will transform the company internally by being true to our coffee core and by doing what will be best for customers, not what will boost comps.”

Starbucks Vs S&P500 (normalised) 2000-2020 [source:Bloomberg]

“It is difficult to overstate the seductive power that comps had come to have over the organisation, quite literally becoming the reason to exist and overshadowing everything else.”

“We [had] predicated future success on how many stores we opened during a quarter instead of taking the time to determine whether each of those stores would, in fact, be profitable. We thought in terms of millions of customers and thousands of stores instead of one customer, one partner, and one cup of coffee at a time.”

“We had to replace our comps-at-any-cost mind-set with a customer-centric one.”

“From where I sat as ceo, the pieces of our rapid decline were coming together in my mind. Growth had become a carcinogen. When it became our primary operating principle it diverted attention from revenue and cost-saving opportunities, and we did not effectively manage expenses such as rising construction costs and additional monies spent on new equipment, such as warming ovens. Then as customers cut their spending, we faced a lethal combination – rising costs and sinking sales – which meant that Starbucks’ economic model was no longer viable.”

“Success is not sustainable if it’s defined by how big you become. Large numbers that once captivated me – 40,000 stores! – are not what matter. The only number that matters is ‘one’. One cup. One customer. One partner. One experience at a time. We had to get back to what mattered most.”

“As Starbucks now knew all too well, growth for growth’s sake is a losing proposition.”

“Growth, we now know all too well, is not a strategy. It is a tactic. And when undisciplined growth became a strategy for Starbucks, we lost our way.”

Losing Focus

“We also extended our brand beyond our coffee core and into areas like entertainment. Where once we sold a couple of CD’s – artful compilations we played in stores – soon we were displaying kiosks packed with the music of an array of musicians… The business deals looked great on our profit and loss statements. It would be a while before I recognised that Starbucks’ amplified foray into entertainment, while it had its upside, was another sign of hubris born of a sense of invincibility.”

“We were venturing into unrelated businesses like entertainment. And we were pushing products that deviated too far from the core coffee experience.”

Maintain Smallness

“It was all too easy to assume that an almost $10 billion company could not operate with the perspective of a single merchant fighting for its survival. But wasn’t every Starbucks store a single merchant? Yes, was my position, and I was adamant that we should think of ourselves as such.”

Simple Model

“Starbucks’ ability to build and operate profitable stores had succeeded for years because we had adhered to a simple yet ambitious economic model; a sales-to-investment ratio of two to one. During a Starbucks store’s first year in business, it needed to bring in $2 for every $1 invested to build it. If the company spent $400,000 to lease and design a store, for example, we expected and always got at least $800,000 in revenue in the first 12 months of operation. Historically, the average store in the US had bought in about $1m annually. These so-called unit, or store, economics were widely known to be best in class because few, if any, retailers could achieve what Starbucks had accomplished year after year. But in 2008, Starbucks was, for the first time in history, missing that ratio at hundreds of stores… Many of our under performing stores had been opened in the last two years, revealing a lack of discipline in real estate decisions that was, in my opinion, an example of the hubris that had taken hold.”

Love

“There is a word that comes to mind when I think about our company and our people. That word is ‘love’.”

Mistakes

“Celebrate, learn from, and do not hide from mistakes.”

“We have made many mistakes over the years, and we will continue to make them.”

Product

“We are in the people business and always have been.”

“People come to Starbucks for coffee and human connection.”

“Starbucks coffee is exceptional, yes, but emotional connection is our true value proposition. This is a subtle concept, often too subtle for many business-people to replicate or cynics to appreciate. Where is emotion’s return on investment? they want to know. To me, the answer has always been clear. When partners like Sandie feel proud of our company – because of their trust in the company, because of our values, because of how they are treated, because of how they treat others, because of our ethical practices – they willingly elevate the experience for each other and customers, one cup at a time. I could not believe any more passionately than I already do in the power of emotional connection in the Starbucks Experience. It is the ethos of our culture. Our most original and irreplaceable asset.”

“The Starbucks Experience – personal connection – is an affordable necessity. We are all hungry for community.”

“I always say that Starbuck is at its best when we are creating relationships and personal connections. It’s the essence of our brand, but not simple to achieve. Many layers go into eliciting such an emotional response.”

“I strongly believe that if we protect, preserve, and enhance the experience to the point where we really demonstrate that the relationship we have with our customers is not based on a transaction, that we’re not in the fast-food business, and then let the coffee speak for itself, we’re going to win.”

“We would reignite the emotional attachment with customers. Unlike other retailers that sold coffee, the equity of Starbuck’s brand was steeped in the unique experience customers have from the moment they walk into a store.”

“Every little act matters: A store manager’s job is not to oversee millions of customers transactions a week, but one transaction millions of times a week.”

“Our intent to create a unique community inside the company as well as in our stores has, I think, separated us from most other retailers.”

Values

“In business, as in life, people have to stay true to their guiding principles. To their cores. Whatever they may be. Pursuing short-term rewards is always short-sighted.”

Source: Starbucks.com

Tone from the Top

“How leaders embody the values they espouse sets a tone, an expectation, that guides their employees’ behaviour.”

Innovation

“Innovation is in our DNA.”

“Going against conventional wisdom is the foundation of innovation, the basis for Starbucks’ own existence.”

“The best innovations sense and fulfil a need before others realise the need even exists, creating a new mind-set.”

“I remember investors whom I had approached to fund Il Giornale bluntly saying they thought I was selling a crazy idea. That I was out of my mind. Insane! ‘Why on earth do you think this is going to work? Americans are never going to spend a dollar and a half on coffee.”

“Any market [eg instant coffee] that had not seen innovation for decades was ripe for renewal.”

“Innovation, as I had often said, is not only about rethinking products, but also rethinking the nature of relationships. When it came to our customers, connecting them in a store and online did not have to be mutually exclusive.”

“Every company must push for self-renewal and reinvention, constantly challenging the status quo.”

Culture

“The very foundation of Starbucks, our true competitive advantage, is our culture and guiding principles.”

“Creating an engaging, respectful, trusting workplace culture is not the result of any one thing. It’s a combination of intent, process, and heart, a trio that must constantly be fine-tuned.”

“Every small gesture mattered, and so much of what Starbucks achieved was because of partners and the culture they fostered.”

“Starbucks is not a coffee company that serves people. It is a people company that serves coffee, and human behaviour is much more challenging to change than any muffin recipe or marketing strategy. Many of the decisions I was making confounded others because they did not grasp the intangible value of preserving the company’s culture.”

Brand

“A well-built brand is the culmination of intangibles that do not directly flow to the revenue or profitability of the company, but contribute to its texture. Forsaking them can take a subtle, collective toll.”

“Every brand has inherent nuances that, if compromised, will eat away at its equity regardless of short-term returns.”

“Each store’s ambiance is the manifestation of a larger purpose, and at Starbucks each shop’s multidimensional sensory experience has always defined our brand. Our stores and partners are at their best when they collaborate to provide an oasis, an uplifting feeling of comfort, connection, as well as a deep respect for the coffee and communities we serve. Starbucks Coffee Company’s challenge has always been to authentically replicate this experience hundreds upon thousands of times.”

Marketing

“Unlike other brands, Starbucks was not built through marketing and traditional advertising. We succeeded by creating an experience that comes to life, in large part, because of how we treat our people, how we treat our farmers, our customers, and how we give back to communities.”

“I have never embraced traditional advertising for Starbucks. Unlike most consumer brands that are built with hundreds of millions of dollars spent on marketing, our success had been won with millions of daily interactions. Starbucks is the quintessential experiential brand – what happens between our customers and partners inside our stores – and that has defined us for three decades.”

Reinvigorating the Brand

“The only filter to our thinking should be: Will it make our people proud? Will this make the customer experience better? And will this enhance Starbucks in the minds and hearts of our customers?”

No Silver Bullet

“Yes, opportunities to transform Starbucks for profitable, sustainable growth existed everywhere, but no single move, no product, no promotion, and no individual would save the company. Our success would only be won by many. Transforming Starbucks was a complex puzzle we were trying to piece together, where everything we did contributed to the whole. We just had to focus on the right, relevant things for our partners, our customers, for our shareholders, and for our brand.”

Hubris

“Perhaps because we viewed the company as too good to fail, we did not work or operate the business as wisely as we should have. Rarely did we make the effort or take the time to step back and question whether we made the most of our resources.”

Visit Stores

“I prefer to visit stores in person rather than read spreadsheets.”

“I also visited our stores and our roasting plants, and almost daily I made a point of walking the floors of our home office, up and down the stairs multiple times, saying hello to people working at their desks, often stopping to chat.”

Seek Feedback

“Our open forums are brief and unscripted, and anyone can ask any question with no fear of retribution.”

Change

“I had written hundreds of memos during my 26 years at the company, and all had shared a common thread. They were about self-examination in the pursuit of excellence, and a willingness not to embrace the status quo. This is a cornerstone of my leadership philosophy.”

Difficult Choices

“I wasn’t returning to the chief executive post intent on being liked. In fact, I anticipated that many of my decisions would be unpopular with various constituents.”

Know the Customer

“Starbucks was building a rich database that we could use to better understand our customers behaviour and reward them accordingly. The card program was a truly, sustainable, competitive advantage for us in the marketplace.”

Humility

“There is never a finish line.”

Competitive Advantage

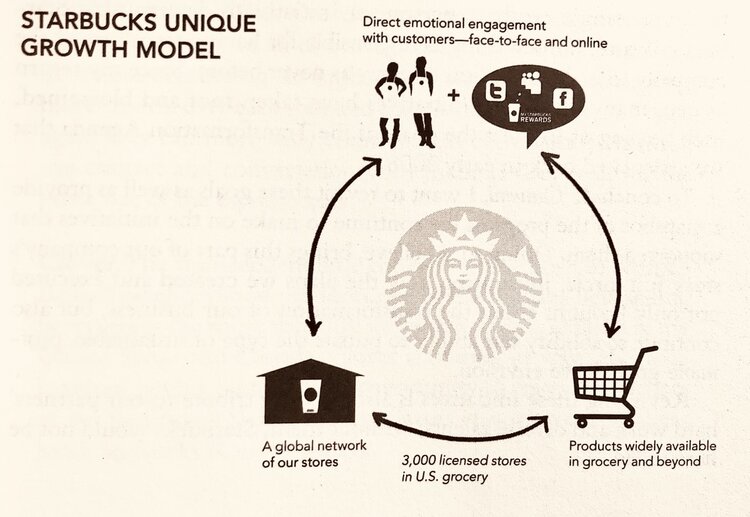

“There are companies that operate huge global networks of retail stores, like us. Others distribute their products on grocery shelves all over the world, like us. And a few do an extraordinary job of building emotional connections with their customers, as we have learned to do. But only Starbucks does all three at scale, and we increasingly see a future where each complements the other, forming a virtuous cycle that allows us to go to market and grow the company in a unique way.”

Source: ‘Onward’ by Howard Schultz

Costs

“The work to keep costs in check will never end, and the challenge ahead is to sustain what we have achieved and strive for more while continuing to wisely invest in our people, in growth, and in innovation.”

Summary

A decade of solid growth and share price performance set the stage for Starbucks’ undoing. Past success meant Wall Street demanded more growth, more stores and more comp sales. Starbucks’ management obsessed over meeting the market’s demands and in the process neglected the deep reality of the business.

Jim Collins opined on Wall Street’s obsession with growth in his book, ‘How The Mighty Fall’:

“Public corporations face incessant pressure from the capital markets to grow as fast as possible. But even so, we’ve found in all our research that those who resisted the pressures to succumb to unsustainable short-term growth delivered better long term results by Wall Street’s own definition of success, namely cumulative returns to investors.”

Howard Schultz’s return as ceo refocused the company on the central engine of its success: customer relationships and innovation. Both qualitative factors. To Wall Street’s dismay, he stopped reporting comp sales. He set about re-engaging and re-invigorating the partner/customer relationships. Often such relationships are the key to a company’s success. Nicholas Sleep of Nomad Partners expressed this concept in his investor letters:

‘As time goes by, the performance that you receive, as Partners in Nomad, is the capitalisation of the success of the firms in which we invested. To be precise, the wealth you receive as partners came from the relationship our companies’ employees (using the company as a conduit) have with their customers. It is this relationship that is the source of aggregate wealth created in capitalism.’

Sleep recognised human attributes often are what lead to success, attributes which have ‘hardly changed in a millennia’.

‘When we study truly great businesses we find that very often it has been simple human attributes that have led to their success.’

It’s the reason Sleep focused on the bond between businesses and their customers.

‘There are so many distractions… It is all too easy to make things more complicated than they need to be or, to invert, it is not easy to maintain discipline. One trick we use when sieving the data that passes over our desks is to ask the question: does any of this make a meaningful difference to the relationship our businesses have with their customers? This bond (or not?) between customers and companies is one of the most important factors in determining long term business success. Recognising this can be very helpful to the long-term investor.’

It will be this bond that determines the fate of Starbucks.

Further Reading

‘Learning from Howard Schultz’ – Investment Masters Class. 2017

’Onward – How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul’. Howard Schultz. 2011. Rodale.

Article by Investment Masters Class