By all rights, 2022 should be the worst year of PennyMac Financial Services’ young life.

The Federal Reserve’s six interest rate increases this year have more than doubled the cost of PennyMac’s mortgage loans inside of 12 months.

And in October, the Foundation for Financial Journalism’s investigation into PennyMac noted that the company, as the Ginnie Mae universe’s second largest lender, has massive economic obligations that remain entirely undisclosed to its investors.

Q3 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Despite all of that, PennyMac gives the impression it’s hanging in there.

Which is exactly what PennyMac’s CEO, David Spector, and its CFO, Daniel Perotti, want shareholders to believe.

But the hardy souls who actually open up PennyMac’s third-quarter 10-Q filing are likely to have a very different reaction.

Because drilling down into PennyMac’s quarterly filings reveals the financial institution’s filthy secret: All year, its management has used a series of non-cash maneuvers to goose its net income. Though one of the older tricks in the earnings manipulation playbook, it is still devastatingly effective at tricking analysts and investors.

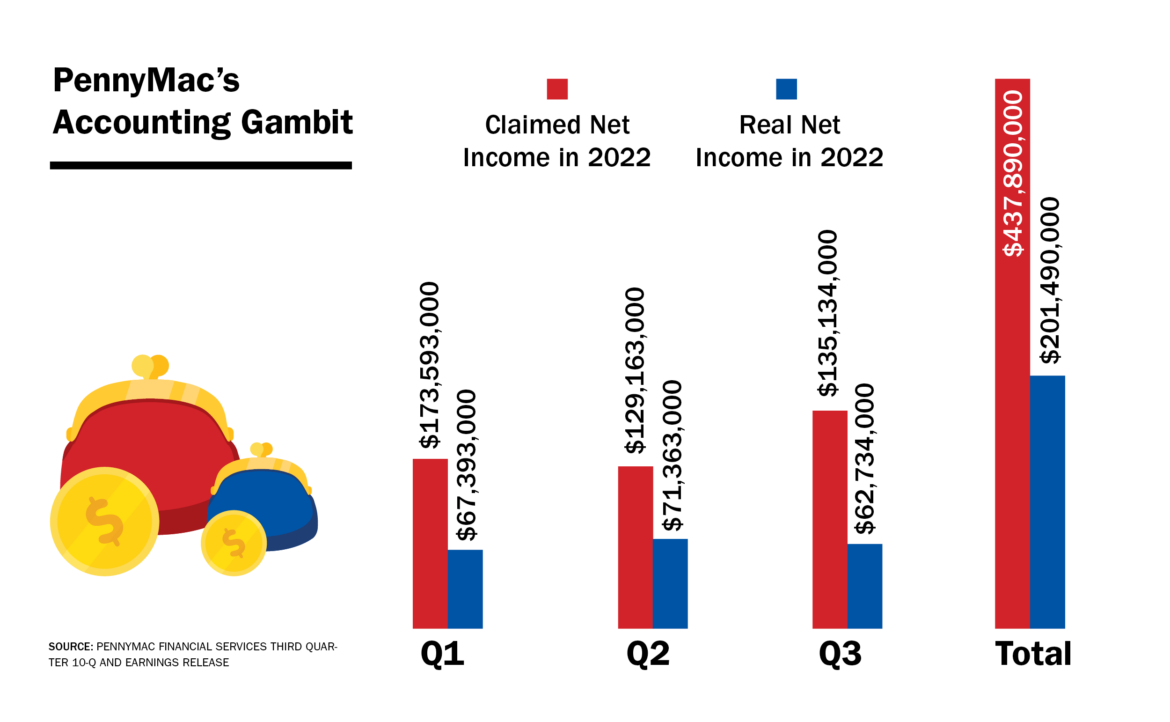

The result is that through September 30, PennyMac’s real net income — with the so-called paper, or non-cash, entries reversed out — is less than half of what management has reported it to be to investors.

Nor is PennyMac’s income statement the only place where management is making self-serving decisions.

The lender also values its mortgage servicing rights, the balance sheet’s largest asset, in a way that is completely out of line with public market data.

The problem for PennyMac is that the overvaluation appears to be between 20 percent and 40 percent. Correcting it would require a write-down of the asset’s carrying value, engendering a cascade-like effect, with the full amount of the write-down to be expensed on the income statement. In turn, this might trigger some debt covenants.

Finally, in October, the value of PennyMac’s delinquent loans spiked to over $13.7 billion, a nearly $1.5 billion increase from September. And more than $5.1 billion of PennyMac’s loans have now been delinquent for 90 days or more. This is an amount nearly 1.5 times greater than the company’s shareholder capital.

What drove this spike in delinquencies? PennyMac has been mum. But it’s a safe bet that the epic property damage left in Hurricane Ian’s wake, especially in southwest Florida where the storm made landfall on September 28, is at least a factor. (PennyMac has $20 billion in loans to Fla. residents.)

Readers will recall that Ginnie Mae requires the lender to dip into its own pocket and assume the delinquent borrower’s principal and interest payments, or alternatively, to buy the loan at par from its mortgage-backed security pool.

Based on PennyMac’s recent 10-Q, it’s not clear how the lender will be able to meet these ballooning obligations.

Earnings sleight-of-hand

In all three of PennyMac’s quarterly reports this year, the lender has used a classic accounting trick to artificially inflate its earnings.

Here’s how the three-step gambit works: First, PennyMac declares that its mortgage servicing rights portfolio has appreciated in value. Second, the company subtracts any hedging-related losses from the appreciation. And third, the difference is then placed on the company’s income statement as pretax income.

If this doesn’t sound anything like GAAP, or generally accepted accounting principles, that’s because it is not. Basically, it is a non-GAAP accounting fiction whose sole justification exists in the heads of company management.

PennyMac, however, is not alone in including MSR valuation changes on its income statement. Publicly traded Ginnie Mae lenders including UWM Holdings and Rocket Companies’ Rocket Mortgage also do it, though loanDepot and Mr. Cooper Group (formerly Nationstar Mortgage) do not.

While PennyMac’s utilization of MSR valuation adjustments is misleading, it is also legal. The Securities and Exchange Commission allows corporate management latitude in how it presents and discusses company results. (In annual and quarterly reports, non-GAAP measures must be identified as such, and GAAP-compliant measures must be afforded equal prominence in the filing.)

But without the company jiggering its MSR valuation skyward, PennyMac’s market capitalization would almost certainly be a lot smaller.

In the lender’s third-quarter earnings release, for example, the MSR valuation scheme added $72.4 million to the company’s pretax income. Adding up the amounts of these maneuvers as disclosed in the three earnings releases through Sept. 30, a total of $236.4 million was added to PennyMac’s stated net income, bringing it to $437.89 million.

So just under 54 percent of PennyMac’s profits, as disclosed in its three most recent earnings releases, may be considered dubious.

All of which makes the gap between PennyMac’s $201.49 million in real net income through Sept. 30 and the $830.40 million in real net income for the same period last year striking.

But there is another, starker way of looking at this issue.

Through Sept. 30, PennyMac claims its net income was down 48 percent from the prior year. Remove the so-called adjustment, however, and its real net income declined more than 75 percent year-over-year.

The $2.46 in earnings per share PennyMac reported allowed it to handily beat analyst estimates, which were between $1.13 and $1.25 per share.

Unsurprisingly, on Oct. 28, the day PennyMac released its third-quarter results, the share price shot up $3.20 to $55.18. The day before, the company’s stock price had jumped almost $4 to $51.18.

Thus, with a few keystrokes, PennyMac added $367.27 million to its market cap.

(One research analyst, Piper Sandler’s Kevin Barker, liked the results enough to raise his price target for the stock to $82 from $78.)

What are MSR valuation adjustments doing on PennyMac’s income statement? It’s a fair question, since the company otherwise carries its mortgage servicing rights on the balance sheet.

The Foundation for Financial Journalism asked J. Edward Ketz, an associate professor of accounting at Penn State’s Smeal College of Business, to examine PennyMac’s MSR valuations.

Ketz, who has written about fair value issues in his analysis of Fannie Mae and other large companies, said the MSR valuation adjustment left him with more questions than answers.

“How are they measuring these [MSR adjustments]? How is this helping their earnings?”

He said that tactics designed to dress up the bottom line have always spoken to a company having a weak quality of earnings.

Ketz said that he assesses a company’s quality of earnings by dividing its free cash flow by its net income.

“A mature company that is doing well should have [that ratio] over one,” said Ketz. In PennyMac’s case, Ketz said the ratio was 0.61, which “indicates a quality of earnings problem.”

(Quality of earnings is an accounting term that refers to the degree to which corporate earnings can be said to accurately reflect a business’s underlying operating fundamentals. Per Ketz’s comment, a key component of that assessment holds that the smaller the difference between a company’s free cash flow and its net income, the higher its quality of earnings.)

An indefensible MSR valuation

The games PennyMac is playing by overvaluing key assets on its balance sheet is an order of magnitude more serious than trying to keep its share price stable.

Based on the Foundation for Financial Journalism’s reporting, PennyMac’s Ginnie Mae MSR portfolio is carried on its balance sheet at a valuation up to 40 percent above what other financial institutions are willing to pay for it.

Because PennyMac has pledged virtually the entirety of its MSR portfolio as collateral for loans to fund its operations, a significant decline in MSR value would require the lender to post additional collateral.

And since MSRs make up more than 34 percent of PennyMac’s $16.36 billion third-quarter balance sheet, investors deserve an explanation.

First, however, let’s take a step back and look at what, exactly, a mortgage servicing right is.

A mortgage servicing right allows the holder to collect a borrower’s monthly mortgage payment. The servicer must then split the payment into principal and interest, as well as keep detailed records of those balances. The servicer also has to collect and pay the loan’s underlying property taxes and insurance premiums. (They are also required to keep detailed records of these transactions.)

Traditionally, when interest rates go up, servicing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgages becomes more profitable for the MSR holder because homeowners are less likely to sell their property and more likely to pay off their mortgage. In those cases, increasing the MSR’s estimated carrying value is reasonable.

But that’s not necessarily going to be the case for Ginnie Mae MSR holders. When rising interest rates combine with a slowing economy, borrower delinquencies — particularly among Federal Housing Administration borrowers — usually spike.

In PennyMac’s case, the $5.66 billion carrying value assigned to its MSRs is the result of some strange math.

The lender’s MSR calculation starts out straightforward enough: The 36 basis points servicing fee — its revenue from servicing loans — is multiplied by $303.8 billion, which is the unpaid principal balance of loans it services.

The next step is where things get strange.

The product, $1,093,680,000, is multiplied by a so-called “servicing fee multiple,” or 5.19, to arrive at the MSRs’ value on the balance sheet.

The origin of the 5.19 number is murky. Despite its centrality to PennyMac’s balance sheet, the lender’s filings and management calls hardly touch on it.

This brings up some obvious questions: What is a servicing fee multiple? How did PennyMac come up with it? And is that 5.19 multiple reasonable?

As far as facts indicate, the answers appear to be: Think of it as a price-earnings ratio for MSRs; absolutely no idea; and almost certainly not.

Taking those questions from the top, a servicing fee multiple is a standard mortgage finance term. It is the multiple of a lender’s current annual servicing fee revenue that a prospective buyer is willing to pay.

Like the use of the price-earnings ratio in equity investing, a servicing fee multiple allows a rudimentary, apples-to-apples comparison of the servicing assets of similar mortgage lenders.

Figuring out how PennyMac arrived at 5.19 as an appropriate servicing fee multiple is much less clear.

The company’s SEC filings categorize its MSRs as a so-called Level 3 asset, which the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants defines as an asset for which “unobservable [price] inputs [are] to be used in situations where markets don’t exist or are illiquid.”

(The phrases “Level 3 assets” and “unobservable inputs” have a great deal of meaning on Wall Street. They first came into widespread use during the Global Financial Crisis, and remain shorthand for “self-marked assets,” in which the holder uses its own methodology to determine value.)

PennyMac put together an internal unit called the Financial Analysis and Valuation group to price these assets. And to that end, the lender published a chart that laid out the various criteria the FAV group used. The 5.19 figure, as such, is not discussed.

“Fair value” is in the eye of the MSR holder

Notably, the justification for PennyMac’s self-valuation regime is that a credible market doesn’t exist for its MSRs.

But that’s flat-out wrong.

A reliable inter-lender MSR market has existed for decades, facilitating trades between commercial banks, investment managers, and independent mortgage banks.

And this market very much includes Ginnie Mae MSRs, according to Mike Carnes, managing director of MSR valuation at Mortgage Industry Advisory Corporation.

Carnes told the Foundation for Financial Journalism that a “real, two-way” market exists for Ginnie Mae MSRs, with regular bid and offer indications among its participants.

He estimated that he gets “10 to 12 Ginnie Mae [MSR] buyers per quarter,” compared to “65 to 75 [buyers for] agency [MSRs.]”

(Contrary to PennyMac’s assertions, this would appear to make PennyMac’s MSRs, for accounting purposes, a Level 2 asset. That is, price discovery is clearly available, but it is intermittent enough that an asset holder can use pricing models to obtain “fair value.”)

A notable feature of the MSR market is that the servicing fee multiple is used when quoting a price. For instance, a Ginnie Mae lender may offer a block of MSRs for sale at a multiple of 4 — or 4x, in trader parlance — whereupon a buyer may counter the lender with a 3.5x bid.

Asked where PennyMac’s 5.19x service fee multiple fits into the current market framework, Carnes said, “It is way above market,” an assessment he later tempered by describing it as “aggressive.” He added that it’s been over 20 years since he’s seen Ginnie Mae MSRs trade above 5x.

Carnes said that the current Ginnie Mae MSR “fair value,” or where he said he had brokered trades, is a servicing fee multiple of 3x to 3.25x. This is in contrast to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MSR trades, Carnes said, where trading is happening between 4.5x and 4.8x.

PennyMac is an engaged participant in the MSR market Carnes himself works in, he said.

“[PennyMac] regularly looks at [MIAC’s] offerings and seeks out market color from us so they very much know where deals are trading.”

Asked for his opinion on PennyMac’s MSR valuation, Carnes said, “[PennyMac] is likely just flat out ignoring what the market is.”

But, Carnes added, PennyMac is within its rights to alter the valuation, citing the FSP 157-4 rule framework that permits the asset (or liability) holder to augment market-price inputs with their own if market-price activity is infrequent or erratic.

“Like most, [PennyMac] recognizes that there is a difference between ‘fair’ market and where deals are trading at present,” Carnes said. “It just comes down to their definition of ‘fair,’ which is likely being influenced by their specific economics.”

Article by