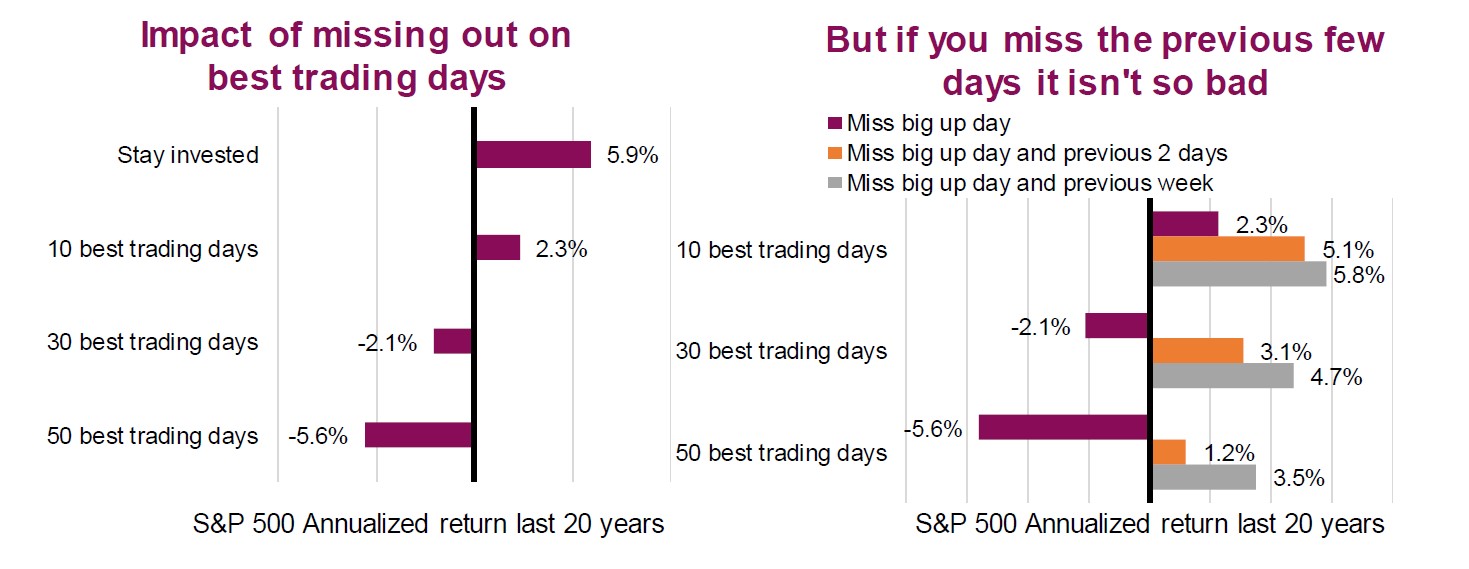

One of the more popular charts that the ‘financial marketing machine’ often uses to convince investors to remain invested and not make rash decisions during periods of market volatility is the ‘what if you miss the best 10 days’ chart. We certainly are in total agreement with the sentiment of this analysis but want to point out that it’s using math to mislead. The fact is, most of those huge ‘up’ days for the market that would supposedly impede your investment performance if you missed them, come shortly after huge ‘down’ days. Volatility clusters that way. The chart below is an analysis of the S&P 500 over the past 20 years, from June 1999 to June 2019. On the left panel it shows that staying invested would have resulted in an annualized 5.9% return. This is slightly below the longer-term average due to the starting point being in the late stages of the tech bubble. Nonetheless, if you missed the best 10 days, of the 5,036 total trading days, you would only experience a 2.3% annualized return. If you miss the best 30 or 50 days, this drops to -2.1% and -5.6%, respectively. Clear evidence you should just stay the course? Not so fast.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Pretty much all those big ‘up’ trading days come right after big ‘down’ days. If you miss the biggest 10 ‘up’ days but also miss the two trading sessions before those big ‘up’ days, your return over the 20 years would be 5.1%. This still amounts to a drop from 5.9% but not nearly as much. If you missed the previous week, your return would have been roughly equal to the staying invested scenario (right panel of the chart). It’s also worth noting that it would be equally as impossible to miss the 10 best ‘up’ days as it would be to miss the 10 worst ‘down’ days. If you could miss the 10 worst days, your annualized return over the past 20 years would be a healthy 9.9% compared to 5.9%.

Given none of us could ever manage to avoid either the best or worst trading sessions, lets bring it back to reality. There are effective tactical strategies that can enhance return or reduce risk, but these need to have a process. The problem is that many investors become tactical as a knee-jerk reaction to market volatility. Sticking with your long-term asset allocation and then running to cash when the market is already down 10% is not an effective tactical strategy. The only effect it would likely have is to make reaching your long-term goals much harder to achieve.

To be tactical or not tactical

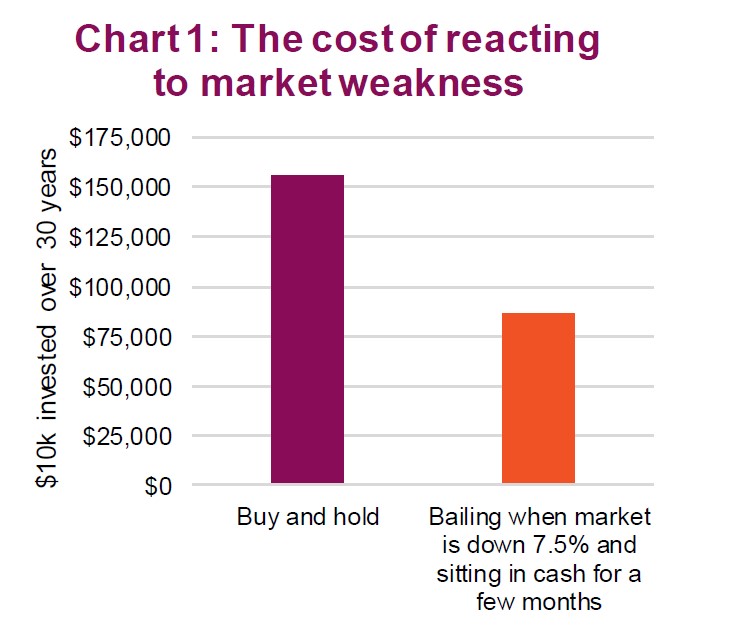

There really is no room in the middle – being part-time tactical is not a good idea. If you like to stick with your long-term asset allocation but tend to become emotionally stressed when markets are volatile, the best path for you is likely not to try and be tactical. Over the past 30 years, if you sold out of the S&P 500 when it was down 7.5% and sat in cash for six months, you could have grown $10K into $86K. However, if you never sold you would have grown your pool to $156K (Chart 1). This is the cost of being lured off course due to market volatility, aka weakness. If you suffer from ‘reactiveness’ an d tend to respond to emotionally charged market environments, it is likely best to work more closely with a professional who can help you avoid making an emotional mistake and help keep you on course.

Some more successful approaches to being tactical

There are ways to improve performance or better control risk by implementing a tactical component to an investment process. However, knee-jerk reacting to market weakness is not one. Below we have outlined a few tactical approaches that have been successful in the past. Generally, when we say ‘tactical’ we are referring to making slight alterations to your asset allocation around a baseline determined by your long-term investment objectives. This is more about nudges and not running from 100% equity to 100% cash.

Valuation

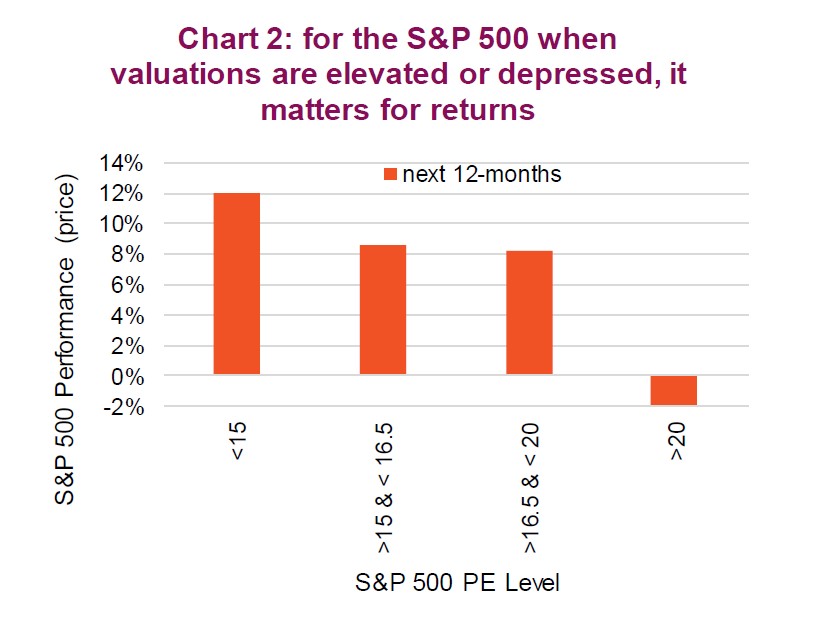

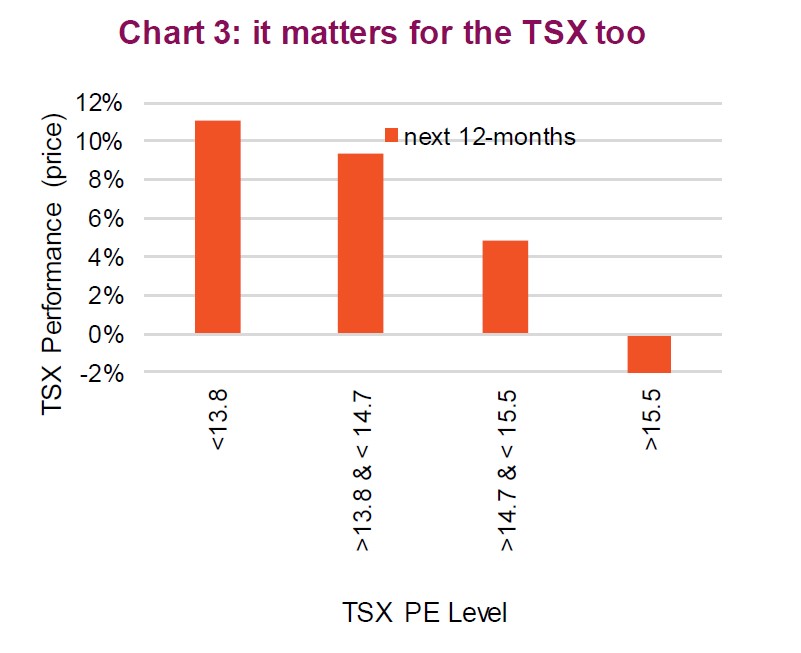

Valuations do matter. If you buy something for less, there is less risk than if you paid more for it. And the long-term evidence supports the fact that valuations at the time of purchase can have a dramatic impact on returns. This is a type of value investing. At mo st times, valuations don’t appear to have much of an impact on returns, but they do when either elevated or depressed. Chart 2 is the average performance of the S&P 500 for one year based on different valuation -level entry points. As you can see, when the price-to-earnings ratios is below 15x, returns have been elevated. When valuations are high, over 20x, returns are abysmal. See Chart 3 for similar supporting evidence of the importance of valuation in the Canadian context.

One simple approach would be to trim equity exposure when valuations are elevated and increase equity when valuations are depressed.

Multi-disciplinary

Markets rise and fall all the time; but if you take a big step back from the daily or monthly noise, the pattern is straightforward. If the global economy is expanding, it tends to be a good time to hold more equities than usual. Of course, this changes when a recession begins or becomes imminent at which time holding less equities or more bonds become timely. Now if you can foresee a recession, investing does become easy. Unfortunately, forecasting recessions is not easy as each one is somewhat different, and the reliability of signals vary from one cycle to the next.

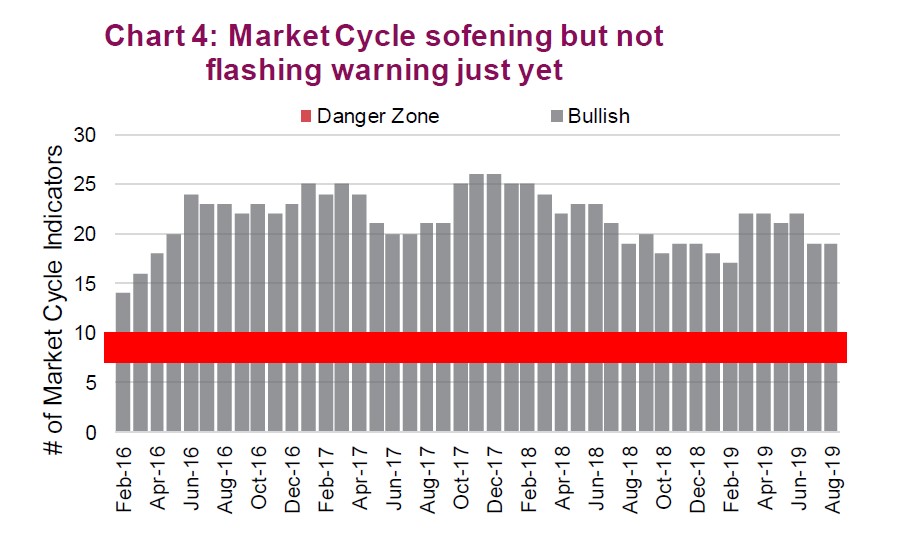

One approach we have championed is using a basket of signals that have in the past provided some efficacy in predicting or identifying a recession. Our Market Cycle framework incorporates signals from market momentum, valuations, fundamentals at the company level, credit, commodity prices and a host of economic data. We believe that relying on a basket of indicators has a better chance of identifying weakness; one signal may work in one cycle and not the next. Essentially, we are diversifying across different indicators in making tactical tilts.

Today, of the 33 signals we rely upon, 19 are positive (Chart 4). While there has been some degradation in signals during the past year, we are still above the danger zone. Currently, this would support no dramatic changes to asset allocation even with some weakness in the global economy. Being disciplined is paramount so that when the signals change substantially, you must react. It may not feel ‘right’ at the time but having a disciplined, process-driven approach, has a better chance of success than following your gut.

Rules based

Relying on a rules-based tactical strategy can also help instil l a level of discipline into your process. The benefits are strong, enabling a tactical strategy that is persistent and testable – for instance, how would this have worked in past periods of market weakness. It also removes emotion, which is often the Achilles heal to making tactical tilts in one direction o r the other. There are negatives to a rules-based strategy: sometimes the rules won’t work – remember every market cycle is different and there is no one solution that will work in every market. Rules-based strategies also tend to have higher transaction costs, which can drag on performance and can be less tax efficient. Still, removing emotion can be a huge benefit and given tactical tilts are often just around a long-term baseline allocation, this different approach can provide a strong diversifier from an overall investment process perspective.

Investment conclusion

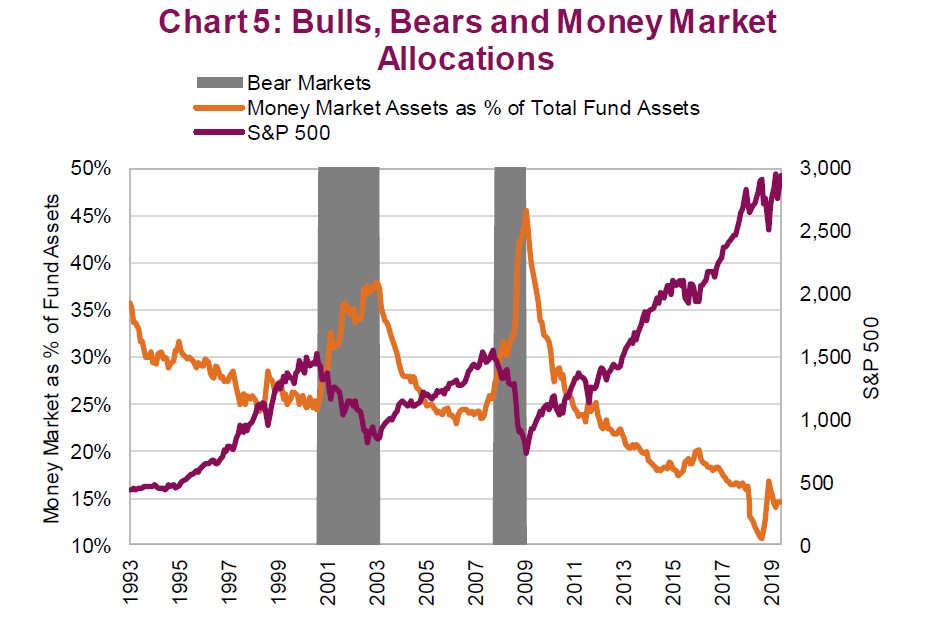

Becoming tactical or changing your asset allocation as a knee-jerk reaction to falling markets is not an investment process, yet it happens all the time. If you, as an investor, suffer from making such mistakes and being lured off course, working more closely with a professional who can help reduce mistakes can add substantial value over time. As evidence this does happen, just look at money market allocations during market cycles. Chart 5 highlights the percentage of mutual fund assets invested in money market funds (yellow line) over time. The S&P 500 (purple line) and past bear markets (grey bars) clearly indicate that at market peaks, investors have the least allocated to cash and at market bottoms the most is sitting in cash.

Successful tactical investors would be the exact opposite.

If you’re a reactionary investor, it may be best to stick with your long-term allocation to avoid mistakes. Alternatively, you can implement a tactical strategy based on a process and not driven by your gut or emotions – this can really enhance performance.

Article by Craig Basinger, Chris Kerlow, Derek Benedet, Alexander Tjiang, Gerald Cheng – RichardsonGMP