One of the key features of any free market is that the main players are always rotating. No one stays on top forever. Economist Mark Perry shows that only 53 companies that featured in the Fortune 500 list in 1955 are still on the list today. Almost 90 percent of them failed, were sold, merged, or fell out of the list. That constant rotation, driven by consumer choices, is what Joseph Schumpeter called creative destruction.

[timeless]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

I have just come by another very compelling demonstration of Schumpeterian creative destruction. This is a phenomenon only seen in relatively free markets. And in a world where every government interferes with virtually every aspect of the economy, free markets are hard to find.

But thanks to the internet, we still have a few. One of them is the market for business chat apps.

A Story of Constant Change

Matthew Guay is a senior editor and writer on the Zapier team. Zapier is an app that connects over a thousand different other apps such as Trello, DropBox, and WordPress. So they have a very good understanding of which business apps are gaining popularity and which apps are losing ground over time.

Last month Guay wrote a very interesting story on how business chat apps evolved over the last few decades. And most did not start as business apps. He began his recollection with AOL Instant Messenger (I also remember ICQ, although it was not in his list), moving to MSN and to Skype, all of them meant for individuals, not companies.

As people began using those apps for work and work collaboration, Campfire (2006) and HipChat (2009) came along expanding the chat functionalities with others specifically tailored for businesses, such as chat rooms and file sharing.

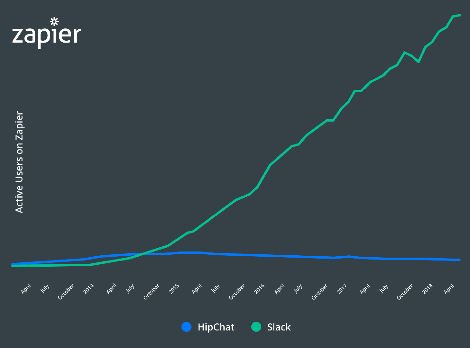

And now there is Slack. According to Guay, Slack today has 88 percent of the team chat market on Zapier. They just crushed the competition.

Recently, Slack acquired HipChat which had previously displaced MSN and Skype as business chat apps. And these had displaced others before that.

As you can see, this is the same story being told over and over. Note how many different chat apps were once king. And then always comes a newcomer who slips in and takes the crown.

Never for long, though. According to Guay, there are already two new strong contenders in the game, Discord and ChatWork.

Why Does This Turnover Happen?

Guay also talks about how Discord is different from Slack. They have some similar features, but a few distinguishing ones make their current growth rates very different. As he puts it, “New ideas built on previous ones are what grow and change the market.” As Matt Ridley puts it, when ideas meet, they have sex and spring new ideas.

So what will be the most-used chat app in businesses fifteen years from now? No one knows. All we know is that no one has ever held that position for long, and there is no reason to believe anyone will. As Guay writes:

The winners aren’t necessarily first. Instead, they grow the market. They take an old idea, approach it from a new direction, and grow the market when suddenly the old idea fits many more use cases. Then someone else takes their concept, respins it, and opens the market a bit more.

Before long, it’s hard to imagine how apps worked before the new category leader defined the category. That’s the creative evolution that makes tech a continuously changing space.

It is actually not just tech. Any market could be like that. The difference in the app market is that it cannot be easily regulated by governments.

Why Doesn’t This Turnover Happen Elsewhere?

Government regulations are designed to protect big players from small rising competitors. By setting requirements to operate in a given market, those requirements are always more easily met by big companies than by small companies. So the big companies may have the extra cost to meet those requirements, but they are also granted a much more profitable long-lasting artificial hold over the consumers.

If a government decided to regulate the app market in their country, developers from other countries would still be able to outcompete that first country’s big players by offering their innovative and cheaper apps in the worldwide app market. So those regulations would serve the local big players no protection at all.

The fact that no government heavily regulates the app industry anywhere only proves that the real purpose of all the other regulations is, as I just explained, to protect big players.

But that is another topic. The point is that any market could work like the app market. People tend to believe that a company’s size itself grants them an everlasting preponderance over their markets.

That is simply not so. If a company cannot use its large size to seize political power (and the fact that they always do is probably what causes people to make the mistaken association between size and lifespan), it will only stay big as long as it keeps serving consumers better than new entrants, which will never be long.

If the people do not entrust their politicians with the power to direct their economy, size becomes no advantage at all. Just as it already happens in the app industry.

Ludwig von Mises was right when he argued that in a free market, the only king is the consumer. Companies struggle to be the one to serve their king. May Slack enjoy their turn as king—of the servants.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

![]()