(N.B. Due to the Labor Day holiday, the next report will be published on September 10.)

[russia]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Last week, we covered Turkey’s geopolitics and history.1 This week, we complete the series, starting with a discussion on Turkey’s economy with a focus on the changes brought by the Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by President Erdogan. We will also examine how foreign debt affects Turkey’s economy and financial system, highlight the impact of the 2016 coup and analyze the causes of the current crisis in Turkey. From there, we will discuss the debt problem and Turkey’s options for resolving the crisis. As always, we conclude with market ramifications.

The AKP’s Economic Program

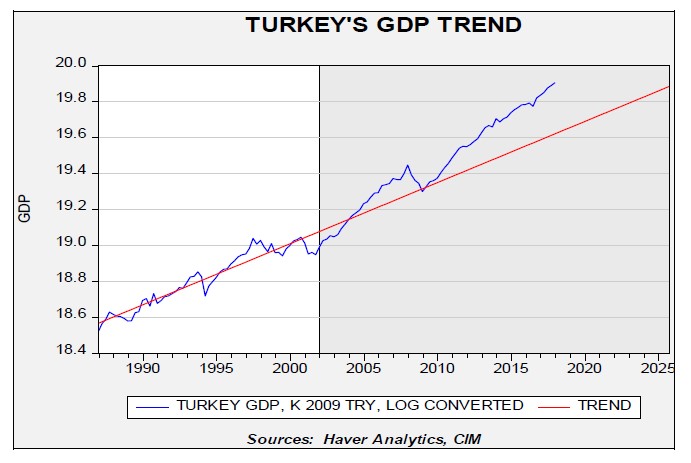

Erdogan’s economic policies have clearly boosted Turkey’s economic growth.

This chart shows Turkey’s GDP; we have log-transformed the data. We have calculated the growth trend from 1987 through 2001, the period of Kemalist rule. Note that since taking control in 2002, Turkey’s GDP has exceeded the previous trend.

The superior growth is also evident in real GDP per capita. The above chart shows this data, with the vertical line indicating the break between the Kemalists on the left and the AKP on the right. The annual compound growth rate during the Kemalist period was 1.1%, while it has averaged 4.2% under the AKP.

Inflation performance has also been superior.

Again, the vertical line shows the break between the Kemalists and the AKP. The AKP was clearly able to better control inflation.

So, how did Erdogan manage to pull off this economic “miracle”? The answer is through an aggressive construction program funded by foreign debt.

This chart shows construction’s percentage to Turkey’s Gross Value Added (GVA). GVA, technically, is equal to GDP plus taxes less subsidies. In other words, for individual sectors of the economy, it is the gross value added to the economy plus the taxes that sector pays less the subsidies it receives. It is a complementary measure to GDP in the national accounts. When the AKP took power in 2002, construction represented around 5% of GVA. Its share has doubled under AKP leadership. In 2002, in terms of share of GVA, construction was the seventh largest sector of the economy. It is now the third largest.2

Only manufacturing and retail/wholesale trade are larger and their shares have been static.

For emerging economies, foreign credit is both a necessity and a curse. Emerging economies need investment funds to build their industrial base. There are essentially two paths to accomplish this task. The first, which has been used by Germany and most nations in the Far East, is to build an export industry by suppressing domestic demand through consumption taxes and an undervalued exchange rate. Restraining consumption creates domestic saving that is used to build the industrial base. This model requires some nation to play the role of “importer of last resort” because the productive capacity created will usually outstrip domestic demand. Without the ability to tap foreign consumption, this model fails.

The second model relies on foreign saving and has been used by the U.S. and South America. In this development model, the emerging economy tries to attract foreign investment, either in the form of debt or equity, to supply the saving for investment. Direct investment has attractive characteristics for an emerging economy; the funds tend to be “sticky” and the investment is difficult to remove if problems develop. However, the emerging economy can suffer some loss of sovereignty with direct equity investment which can make it less attractive. Financial equity investment is somewhat less attractive than direct investment because, absent capital controls, equity shares can be liquidated.

The other vehicle, debt, can come in the form of direct bank loans or financial instruments (bonds, usually). The foreign lender usually prefers to be paid in the lender’s currency, which brings both benefits and costs. On the benefit side, the interest rate on the foreign currency loan is usually lower than borrowing in domestic currency. The cost is that the debt must be repaid in foreign currency. Rising interest rates in the lending country or currency appreciation can boost debt service costs.

The risk of this model is that it is dependent on foreign investors, who can be fickle. In addition, to pay back foreign loans denominated in a foreign currency requires the borrower to acquire foreign exchange. For the entire economy, this means the debt is serviced through a trade surplus. Without a trade surplus, the debt can only be serviced by draining foreign reserves or by attracting new loans.

The next chart shows Turkey’s external debt and the current account, scaled by GDP. When the AKP took office, external debt was very high. However, the Kemalist government was running a current account surplus, making debt service manageable. Turkey’s current predicament is clear—it has rising external debt with a current account deficit.

The combination of a widening current account deficit and rising external debt eventually becomes unsustainable.

The upper line on this chart shows Turkey’s foreign reserves, while the lower line shows the current account. In general, if the current account is in deficit but reserves are increasing, it suggests that incoming investment is offsetting the current account deficit, which is nothing more than the domestic savings/investment balance.3 In other words, a current account deficit indicates that domestic investment is greater than domestic saving. The deficit is either filled by incoming foreign investment or the reduction in foreign reserves. Foreign reserves peaked in 2013 and have been steadily declining as the current account has remained in deficit. Although reserves remain relatively high, they could be drained rapidly if foreign investors abandon Turkey. Investment has been described as being driven by “animal spirits,”4 which can cause rapid shifts in sentiment. A nation that uses the “American” system of development is at the mercy of foreign investors as long as it runs a current account deficit. Thus, the need to maintain investor confidence is critical.

There is one unusual twist to Turkey’s foreign reserves. Modern banking practices require a reserve ratio, a certain percentage of liquidity assigned to each loan in case of default. Under Turkish banking law, a bank extending a loan can use foreign currency denominated liquidity for loan reserves if the forex asset is held at the Central Bank of Turkey. The Central Bank counts these loan reserves as part of its foreign reserves; therefore, the availability of foreign reserves may not be as large as the official data suggest because some of it is “encumbered” as loan reserves. Accordingly, Turkey’s available reserves may be less than they seem.

The 2016 Coup Attempt

Another key element to the current crisis in Turkey is the failed 2016 coup.5 The coup may have been a last-ditch effort of the Kemalists to overthrow the AKP and return Turkey to a secular government. Since the Kemalists had a long history of overthrowing leaders they have deemed to be “too religious,” the failure of this grab for power ended that pattern and probably means the military is no longer secular enough or unified enough to defy the government.

Although the coup nearly succeeded, Erdogan was able to narrowly escape and rallied the country against the plotters. In a wide-ranging purge, security forces not only arrested Kemalists in the military, but the wide net also gathered real and imagined enemies and potential opponents of Erdogan’s rule. The aforementioned Gulenists have faced particular scrutiny.

Fethullah Gulen is a potential threat to the regime; he offers an Islamist alternative to the AKP and the Gulenists are deeply embedded in Turkish society. Thus, Erdogan has worked furiously to eliminate Gulenist sympathizers from Turkey’s political system.

Since the coup, Erdogan has moved steadily to consolidate power. The aforementioned new constitution and recent election has given President Erdogan sweeping authority. The decision to restructure the government and consolidate power is likely a reaction to the failed coup.

The Current Crisis

The proximate cause of the current crisis is the detainment of Pastor Andrew Brunson, a 50-year-old evangelical Christian pastor who has ministered to a small flock of Christians for over two decades. In October 2016, three months after the failed coup, Brunson and his wife were summoned to a local police station for what they assumed was a routine extension of their residency permit. Instead, they were both arrested and charged with “threatening national security.”6 His spouse was released a couple weeks later but Pastor Brunson remains under arrest, although recently he did leave prison under house arrest.

His charges include urging Christian Kurds to foment separatism as part of the coup which Erdogan believes was actually masterminded by Gulen. To a great extent, Brunson’s fate has become tied up in a battle of appealing to political bases. In the U.S., a key part of his support comes from evangelicals, for whom Brunson is a sympathetic character. Vice President Pence, an evangelical Christian, has been especially vocal about Brunson’s plight. At the same time, Erdogan’s base of support are Islamists, who would look askance at the missionary activity of Brunson.

There does not appear to be any evidence that Brunson was part of any coup; in fact, his arrest shows just how wide the net was cast in the post-coup environment. It also looks like Erdogan overplayed his hand with regard to the pastor. It appeared the Trump administration had secured his release, getting Israel to swap a Turkish national accused of aiding terrorists for Brunson. However, the agreement fell through. Instead, Erdogan pushed to have Brunson swapped for Gulen.7 Then, he asked for a Turkish banking executive who had been convicted in New York of aiding Iran in avoiding sanctions. He also wanted a fine reduced against Halkbank for Iran sanctions-busting; the imprisoned bank executive worked for that bank.

The Trump administration’s position has hardened, applying sanctions and adding to them. The U.S. president has indicated he “will pay nothing” to get Brunson back.8 The U.S. has even more powerful tools at its disposal as it could likely pressure the IMF to deny Turkey a bailout package and could keep the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development from offering loans. It isn’t out of the question for the Trump administration to push to deny Turkish banks access to the S.W.I.F.T. network, which would be a crippling blow.

We do expect Erdogan to eventually back down and release Brunson. In fact, we suspect he is seeking some sort of face-saving plan to end this part of the crisis. But, releasing Brunson doesn’t solve the other problems Turkey is facing.

Here are some of the other difficult issues that are undermining confidence in Turkey’s government:

Avoidance of austerity: There is a standard “textbook” approach for countries in Turkey’s predicament. The economy is undersaving relative to its investment; thus, it needs to reduce investment and lift domestic saving, with the idea of reducing the current account deficit and servicing its foreign debt. The orthodox plan is to (a) raise interest rates, (b) introduce fiscal austerity, and (c) petition the IMF for help in easing the liquidity crisis. Unfortunately, due to Erdogan’s reliance on construction, he is loath to raise interest rates; in fact, he has argued that raising interest rates causes inflation. Under normal circumstances, a leader can have all kinds of odd beliefs about how the economy works and foreign investors will tend to tolerate such heterodox comments as long as there is some degree of independence at the central bank and the finance ministry.

However, there are two factors that have undermined foreign investor confidence. First, the new constitution gives the president more power over the central bank governor; his term is shortened and deputies no longer need 10 years of experience as a prerequisite. The second factor is even more damning; in July, Erdogan appointed his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, to the key post of economics and finance minister.9 And, the undersecretaries, which used to be staffed by civil servants, are now political appointees. The latter means there is no group within the government that can reliably deliver information to the president that he may oppose. The former appointment means the central bank’s independence has been at least modestly compromised. In fact, Albayrak’s appointment triggered a sharp sell-off in the lira, which had been the largest depreciation since the coup until recent days.

Military equipment: Erdogan is attempting to purchase F-35s from the U.S. and the S-400 missile system from Russia. The Russian purchase is especially egregious; for a NATO member to buy a Russian missile system is an affront to the alliance. Congress is moving to block the sale of the aircraft as there are legitimate fears that Russian technicians may try to figure out weaknesses in the plane that the S-400 could exploit. Erdogan’s attempt to buy from both nations has hurt relations with the U.S.

Tensions in Syria: Although Turkey has been an avowed opponent of the Assad regime, the Erdogan government also opposes Kurdish forces in the region, which have been allied with the U.S. At times, Turkey’s opposition to Kurdish forces has complicated American efforts against Islamic State.

The Debt Breakdown

Turkey’s external debt is $467 bn, $293 bn of which is borrowed from banks. Spain is the largest bank lender to Turkey, at $82 bn, with French banks second at $38 bn and Italian banks at $17 bn. Spain’s exposure is about 2% of the country’s total bank assets. Thus, a loan default by Turkey would be painful but, on its own, would probably not trigger a banking crisis.

About 85% of the bank loans are out to 2,300 companies. We note that six gas-fired plants were forced to close recently due to higher fuel costs, a consequence of the collapse in the lira. Over the next year, private non-financial borrowers will need to roll over $66 bn in foreign currency debt.10 Of the total foreign currency debt, 78% are denominated in U.S. dollars and 18% are in euros.

Turkey’s Options

Assuming Pastor Brunson is freed in short order, Turkey will still have large foreign debts, an excessive current account deficit and a significant investment/savings imbalance. It will essentially be impossible to maintain the economy’s current trajectory. Here are some potential paths to resolution:

Austerity: This option was discussed above. Although some degree of belt tightening looks inevitable, Erdogan will try to postpone this outcome as long as possible. However, it should be noted that the financial markets will cause some degree of austerity anyway. The lira has declined to excessively weak levels.

This is a purchasing power parity model of the Turkish lira against the U.S. dollar. Purchasing power parity values the exchange rate based on relative inflation. The concept is that the exchange rate should act to equalize prices between countries. The valuation model isn’t perfect; price indexes are not perfectly harmonized across countries and not all goods are tradable. But, in a broad sense, it is useful at extremes. Currently, the lira is nearly six deviations from the fair value calculation. The weak exchange rate will increase import prices and reduce export prices, narrowing the current account deficit by constraining consumption. So, regardless of how Erdogan feels about austerity, he is already getting some from the markets.

New investment: Qatar has already pledged to invest $15 bn into Turkey.11 Although that will help, much more is needed. Turkey might have been able to tap the massive sovereign wealth funds among the Persian Gulf states if not for Erdogan’s staunch support of the Muslim Brotherhood, which has angered Saudi Arabia and other nations in the region. And, Turkey has supported Qatar, which has become something of a pariah among the Persian Gulf states for having warm relations with Iran and for supporting Al Jazeera, which the leaders of these states loathe. China might help, although Chinese terms are often onerous. Russia would probably like to aid Turkey to pull it out of NATO’s orbit, but it lacks the funds to offer serious support.

Migrant retaliation: Perhaps the biggest threat that Turkey could “monetize” would be to open its borders to Middle Eastern migrants. In 2016, Turkey and the EU (read: Germany) came to an agreement under which Turkey would prevent migrants from embarking from its shores into Greece or moving into the Balkans by land. In return, Turkey was to receive €3.0 bn to €6.0 bn in aid. According to reports, Turkey is holding around 3.5 mm refugees.12 It wouldn’t be a shock to see Turkey demand more funds from Europe for keeping these migrants and threaten to become a conduit for even greater flows. Given the precarious political situation in Europe with the rise of populism and a growing reaction against migration, this is a potent threat.

Default: Although default is always a possibility, this option will undermine the Turkish economic model and will likely be a last resort. However, some sort of bank debt restructuring may be possible, especially given that the majority of the bank debt is from European banks and the migrant threat would be significant.

Ramifications

Turkey should probably be viewed in the broader context of emerging markets. When the Federal Reserve is tightening monetary policy and the dollar strengthens, emerging nations that borrowed in dollars often run into difficulties; the various emerging market crises, such as the Mexican Debt Default in the early 1980s, the Tequila Crisis in the 1990s and the 1997-98 Asian Economic Crisis, coincided with either Fed tightening or dollar strength, or both.

The key question for investors is whether the problems in Turkey will spread. By itself, Turkey probably doesn’t cause anything like the Asian Economic Crisis, mostly because most emerging market nations have adopted floating currencies; large depreciations in pegged currencies exacerbated that event. But, that doesn’t mean the current situation isn’t troubling.

Valuation models suggest the dollar is overvalued; the Federal Reserve is raising rates, which should be bullish for the dollar, but that factor is already discounted. The “wild card” is trade policy. If protectionism spreads then the dollar’s reserve currency status will lead other nations to take aggressive steps to secure dollars which will require significant depreciation to offset tariffs. That fear has boosted the greenback recently and could keep the dollar stronger than it otherwise would be. Of course, if progress on restructuring trade is successful then the dollar will likely ease and offer some support for emerging markets.

Clearly, Turkish financial assets will be under pressure for the foreseeable future, although a significant amount of bad news has already been discounted as shown by the weakness in the currency. For now, Turkish assets should be viewed with caution, although the Asian Economic Crisis showed that values do eventually recover.

The other area of concern is the breakdown in relations between the U.S. and Turkey. As we noted early in this report, Turkey sits on prime geopolitical real estate. Any power wanting to influence the Middle East, Central Asia and Europe would want good relations with Turkey. The fact that relations between the U.S. and Turkey have been deteriorating for the past several years does reflect one of our core theses, which is that the U.S. is slowly abandoning its global hegemonic role. Conditions suggest the U.S. is becoming less interested in projecting power in the Middle East. This abandonment will lead to greater global uncertainty and should support defense stocks and commodities.