Over the past few months, Turkey has become a major topic of interest. Recep Erdogan won re-election to the presidency in June 2018. This event was important because a referendum on a new constitution in 2017 gave the office of the president sweeping powers; the previous constitution was based on a parliamentary model which gave more power to the prime minister. According to the referendum, Erdogan could only exercise these new presidential powers after winning a new election.

[russia]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Even before the election, there were signs the economy was overheating. Inflation was increasing and the central bank was not raising rates in a manner consistent with quelling the inflationary pressure. Since the election, an economic crisis has developed, with falling financial asset prices and a sharp decline in the Turkish lira (TRY). In addition, Erdogan has found himself in a contest of wills with President Trump over Americans detained in Turkey. This has led to punitive trade tariffs and threats of additional sanctions.

The goal of this report is to place the current crisis within the context of Turkey’s evolution and development. Part I will examine Turkey’s geopolitics and history. Part II will discuss economic factors, including the impact of foreign debt on Turkey’s economy and financial system. We will highlight the impact of the 2016 coup and analyze the causes of the current crisis in Turkey. From there, we will offer a discussion on the debt problem and Turkey’s options for resolving the crisis. As always, we will conclude with market ramifications.

Geopolitics and History

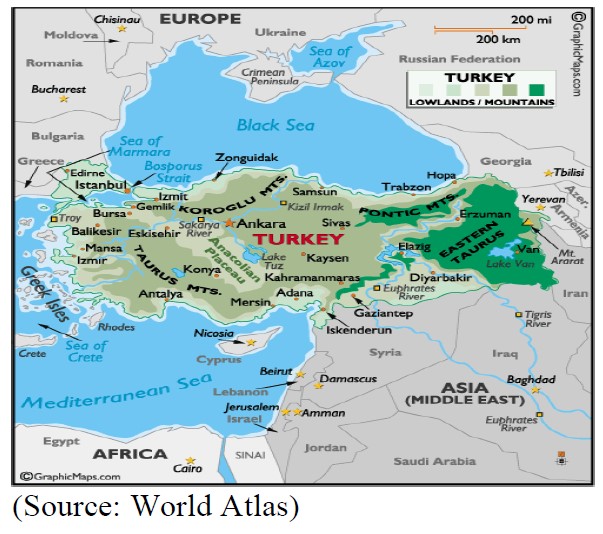

The key to understanding the geopolitics of Turkey rests on understanding the region around Istanbul.

The original Turks who inhabited the area came from central Asia and settled on the land bridge that separates Europe and Asia. This land bridge straddles the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara, which empties into the Aegean Sea. The Turks fully gained control of this area in 1453 with the capture of Constantinople (Istanbul).

This land bridge gave the Turks effective control of two seas, the Black and Marmara, along with the Bosporus Strait and the Dardanelles. The core of original Turkey was this land bridge, not the Anatolian land mass that is modern-day Turkey. By controlling the surrounding seas and plains, the Turks put themselves in the middle of regional trade and economic growth. From this base, the Turks pushed east to create a defensible space on the rugged Anatolian peninsula. The region is mountainous, making it hard to invade; at the same time, these characteristics make it difficult to conquer and control local ethnic and religious groups. But, as long as the Turks controlled the commanding heights, they could fend off potential invaders.

By controlling the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, along with the Anatolian peninsula, Turkey is a defensible state. All Turkish governments must, at a minimum, control these areas.

Turkey’s history can be divided into three phases. The first phase was the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire began in 1299 and ended in 1922. By the late 1600s, the empire was massive.

The Ottomans were successful empire builders partly because they managed their territory with a relatively light touch. They tended to grant a high degree of local autonomy (at least for that time in human history) and showed a remarkable level of tolerance for different religions and ethnicities. As the above map shows, at its peak, the Ottoman Empire projected power into more than half of the Mediterranean Sea, controlled most of the Middle East, including parts of modern-day Iran, and made deep incursions into Europe. However, by the onset of WWI, its holdings had been reduced to Anatolia, the area east of the Bosporus, the Levant, the east coast of the Red Sea and the west coast of the Persian Gulf. And, even in these areas, its degree of control varied.

The collapse of the empire after WWI led to the second phase of Turkey’s history, the creation of modern-day Turkey, formed by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. After the war, European powers attempted to occupy parts of Turkey, including the Bosporus and the Dardanelles. The Allies had tried to prevent the return of the Ottoman Empire by giving autonomy to various regional groups, including the Greeks, Kurds and Armenians. However, a group of Turkish military officers led by Ataturk defeated the occupying powers, overthrew the puppet monarchy and, over time, created the nation of Turkey.

Modern-day Turkey was formed from the structure that Ataturk developed. Called Kemalism, the political structure was designed around two primary concepts, republicanism (as opposed to monarchy) and secularism. The goal was to turn away from the Ottomans’ Islamic roots and to adopt the politics and culture of Europe. The new nation was centered on Istanbul and the surrounding regions of the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits. The Anatolian peninsula, populated with various non-Turkish ethnic groups, came under the rather harsh control of the Kemalist Turks; this was in contrast to the Ottomans, who, as noted above, tended to rule with a less heavy hand. The Kemalists gradually expanded their control of Anatolia, suppressing non-Turkish languages and enforcing a hard separation between the state and religion. The military and the industrialist classes from the Sea of Marmara region dominated Turkey. The Turks concentrated power in the interwar years and remained neutral during WWII.

During the Cold War, Turkey found itself isolated. Greece opposed any Turkish efforts to engage Europe. The Communists were threatening from the Balkans and Central Asia, and the Soviets had developed friendly relations with Syria and Iraq. Furthermore, the Persian Gulf Sunni kingdoms had strained relations with Turkey due to its aggressive secularism.

In response, the U.S. moved to improve relations with Turkey. Turkey’s geography made it a valuable ally as it gave the U.S. the ability to monitor Soviet naval traffic going through the Dardanelles and the Bosporus straits. It also allowed the U.S. to place military assets close to the Soviet Union. U-2 spy planes originated from Turkey and, for a while, nuclear missiles were placed there. Turkey formally joined NATO in 1952, the first enlargement after the treaty organization was formed in 1949.

Kemalist Turkey supported Israel, being one of the first nations to recognize the Jewish state. As U.S. relations with Israel improved after the 1967 Six-Day War, Turkey and Israel became closer allies. Turkey allowed the Israeli Air Force to use Turkish air space for flight training and Turkey was an active buyer of Israeli defense products.

The Turkish military has periodically staged coups, ostensibly to protect the Kemalist vision for Turkey. Coups occurred in 1960, 1971 and 1980; a quiet coup also occurred in 1997. Outside powers generally knew that if the military supported a certain program or decision it would effectively be executed.

The event that ushered Turkey into the current phase was the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. During the Cold War, Turkey was very valuable to the United States and NATO due to its role in containing the Soviet Union. Once the Cold War ended, Turkey’s value declined. Turkey supported the U.S. and its allies in ousting Saddam Hussein from Kuwait during the First Gulf War. At the same time, Islamist sentiment was rising in the Middle East. Islamist jihadists were critical in defeating the Soviets in Afghanistan, a conflict that clearly weakened the U.S.S.R. and contributed to its demise. Devout Islamists were uncomfortable with Saudi King Fahd’s decision to allow Western troops to base in the kingdom during the First Gulf War. Opposition to the “decadent” leaders in the Middle East supported the rise of al Qaeda and other jihadist groups.

Turkey was not immune to this pressure. The secularist government under Kemalist Turkey was facing tensions with Turkey’s suppressed minorities and Islamists. It should be noted that Islamist parties began organizing in the 1970s but were successfully suppressed. By the mid-1990s, however, they were becoming stronger. The Kemalists tried hard to prevent them from gaining power. However, the emergence of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002 marked the beginning of a major shift in Turkish politics, when the party won a sweeping electoral mandate. Still, its leader, Recep Erdogan, was not allowed to take the role of prime minister because of a public reading of a poem in 1994 that judges deemed “Islamic.” In 2003, the ban was lifted and Erdogan took the role of PM.

The AKP was able to dominate elections by becoming a “fellow traveler” with the Gulen Movement. This movement began with a charismatic imam named Fethullah Gulen. Gulen currently resides in Pennsylvania (to avoid arrest in Turkey) and has created a conservative, but politically moderate, Sunni Islamist movement. The Gulen Movement centers on education. Gulen schools, focusing on elementary and secondary education, support a strong scientific curriculum. This is very different from the Saudi-supported Madrassas which focus solely on religious education in the Islamic world. The goal of the Gulenists is to educate students to enter the professional mainstream while carrying their Islamic faith into those economic classes. The secular government tried to prevent these students from entering the professions with rules that prevent graduates from religious schools from entering the major colleges in Turkey. However, these rules were reversed as the AKP grew in power.

It is important to note that the Gulen Movement is not restricted to Turkey. It is a global movement with 1,000 schools in 115 countries. Much like the Jesuits, who focused on educating a Catholic-Christian elite, the Gulenists are attempting to build an elite professional and technical socioeconomic class to spread their conservative, but not Salafist, version of Islam.

The Kemalist vision for Turkey has been steadily undermined since the end of the Cold War. Erdogan’s stance is more religious and less Western. In other words, Anatolia is gaining control of the Turkish core that surrounds the Sea of Marmara. This evolution has been steadily changing Turkey’s relations with the West and its neighbors.

Turkey has increasingly moved away from unquestioned support of American policy in the region. It opposed the Second Gulf War when the U.S. and its allies overthrew Saddam Hussein; it did not allow the U.S. to use its airbase at Incirlik for air operations during that conflict. Turkey’s opposition to the war was based on fears that the conflict would bring instability to the region.

Although the AKP government maintained good relations with Israel for several years, Turkey condemned the 2008-09 Israeli-Gaza conflict and excluded Israel from the Anatolian Eagle military exercises, which included forces from Italy, Turkey and the U.S. Likewise, relations deteriorated sharply in the wake of the Gaza flotilla raid in 2010. In this event, Israeli forces boarded a Turkish relief ship that was bound for the Gaza Strip. An altercation occurred and eight Turkish nationals died. It took three years and an apology from Israeli PM Netanyahu to normalize relations. And, it does not appear that relations between Israel and Turkey will return to the close ties observed under the Kemalists.

The third phase of Turkey’s political development is perhaps a synthesis between its Ottoman roots and Ataturk’s vision. The rise of political Islam was undermining the secular state and the Kemalists were unable to grow the economy, in part, because they didn’t expand opportunities for the religious and other ethnic groups outside the Turkish core in the regions of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus straits. Erdogan has worked to include Islamists in the “hinterlands” of Anatolia but has had uneven relations with the Kurds, sometimes wooing them but mostly suppressing them. The third phase, which has so far been dominated by the AKP, is about integrating the “country” Islamists from the Anatolian peninsula with the dominating Turks from the Dardanelles and Bosporus regions. That integration requires a strong economy.

Part II

Next week, we will complete this report with an analysis of Turkey’s economy, focusing on the AKP’s effect on performance. We will discuss the impact of the 2016 coup and analyze the causes of the current crisis in Turkey. We will also discuss the debt problem and Turkey’s options for resolving the crisis. As always, we will conclude with market ramifications.

Bill O’Grady

August 20, 2018