Copper is the blood of the global economy. And in 2005, China couldn’t get enough of it.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Copper is vital for industries ranging from manufacturing to telecommunications. China was the world’s manufacturing hotspot at the time – and in the midst of an epic commodities boom, China needed a lot of copper.

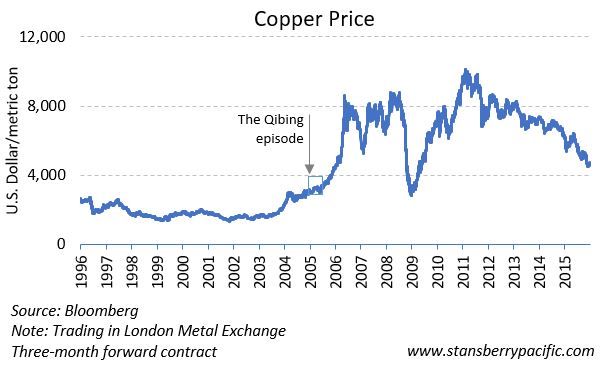

Despite this bullish outlook, at one point in 2005, commodity traders around the world saw that someone in the Chinese government had placed massive bets that the price of copper would fall – to US$3,300 a tonne by year-end. That would equate to a drop of nearly 20 percent.

But copper prices kept going up. No one knew the actual size of China’s short position (when you profit from falling prices). Estimates ranged from 100,000 to 600,000 tonnes – a small fraction of global production. But that was still worth hundreds of millions of dollars on the market.

In the end, China ended up losing US$1 billion by being on the wrong side of copper prices.

What happened?

China’s Communist Party, known for its hands-on management of the nation’s economy, found itself in this position because of one lone trader. His name was Liu Qibing.

Shanghai-based Qibing was a copper futures trader for China’s State Reserve Bureau (SRB), a central government body that stockpiles commodities for the country’s industries.

Like Nick Leeson, whose US$1.2 billion in losses took down Barings in the mid-1990s, Qibing had been a highly profitable trader for years. And like Leeson, Qibing made a series of bad trades – which led him to take increasingly large gambles that had disastrous consequences.

But unlike Leeson, a high-flying and flamboyant egoist, the 36-year-old Qibing was a career Communist Party member who kept to himself. In fact, when the story of the scandal broke, Chinese officials initially denied that Qibing even existed, a claim that wasn’t easily contradicted since he was in hiding at the time.

But like Leeson, Qibing simply walked away from the trading desk after leaving an “I’m sorry” note… and about US$1 billion in leveraged investments.

Qibing joined the SRB in 1995, and he quietly acquired a reputation as a savvy market operator. He reportedly netted the state more than US$300 million by being long on copper as its price surged between 2002 and 2004. Qibing was a star trader.

But in early 2005, Qibing was convinced that China would tighten monetary policy, by raising interest rates, in an effort to cool the economy and dampen inflation. This would normally cause copper prices to fall as well, since China would stop buying so much and demand for copper would fall.

So, he began shorting copper, or selling some of it with the intent to buy it back when the price dropped. When prices went up instead of falling, Qibing started “averaging down,” or buying more to lower his average cost. But this strategy only resulted in bigger and bigger losses.

How Qibing hid his ever-widening losses from authorities is shrouded in mystery. Reportedly, his immediate supervisors helped cover up the fact it got out of control to protect their own reputations. The Communist Party, embarrassed by the entire episode, has not shared many details.

Nonetheless, it is believed that by August 2005, Qibing had committed 130,000 tonnes of copper for delivery in December. The price was then about US$3,300 per tonne. At that point, the losses may still have been manageable enough that he could have kept his job. But, like Nick Leeson and other rogue traders, Qibing reacted to the situation by doubling down – that is, buying more and more of the same tumbling investment.

That decision sealed his fate. Between August and November of 2005, copper prices rose over 12 percent. This caused Qibing’s losses to become a serious problem.

Sometime around November 1, faced with hopelessly large losses, Qibing vanished. By mid-November, stories emerged on London trading desks that a Chinese trader had built a large short position in copper and then disappeared. The rumours drove up the copper price on the futures market even higher, with traders betting that eventually China would have to buy copper to cover Qibing’s short contracts.

Before the year ended, copper traded above US$4,500, up 20 percent from August. China’s final loss from Qibing’s rogue trading is unknown, but estimates range from US$100 million to US$1 billion.

After hiding for more than a year, Qibing reportedly was arrested in a rented apartment in Yunnan Province, in southwestern China. He went on trial in 2008 and was sentenced to seven years in prison. A supervisor also received a multi-year sentence.

What investors can learn from Qibing – and other rogue traders

Liu Qibing’s debacle offers another fascinating study of greed run amok on a grand scale. The episode also highlights the need for companies to better supervise their traders – “star” traders in particular.

It can also serve as a cautionary tale for individual investors. So here are four lessons to take away from Qibing’s story…

- Don’t get overconfident and confuse luck with skill

- Have a plan, or strategy, and stick to it

- Don’t throw good money after bad and cut losses before they cost you too much money

- Don’t double down and expect to recover investment losses

By following these lessons, investors can avoid ruining their own portfolios.

Good investing,

Kim Iskyan

Publisher, Stansberry Pacific Research