Kerrisdale Capital Management presentation discussing their short position in Qualcomm Incorporated.

Q3 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

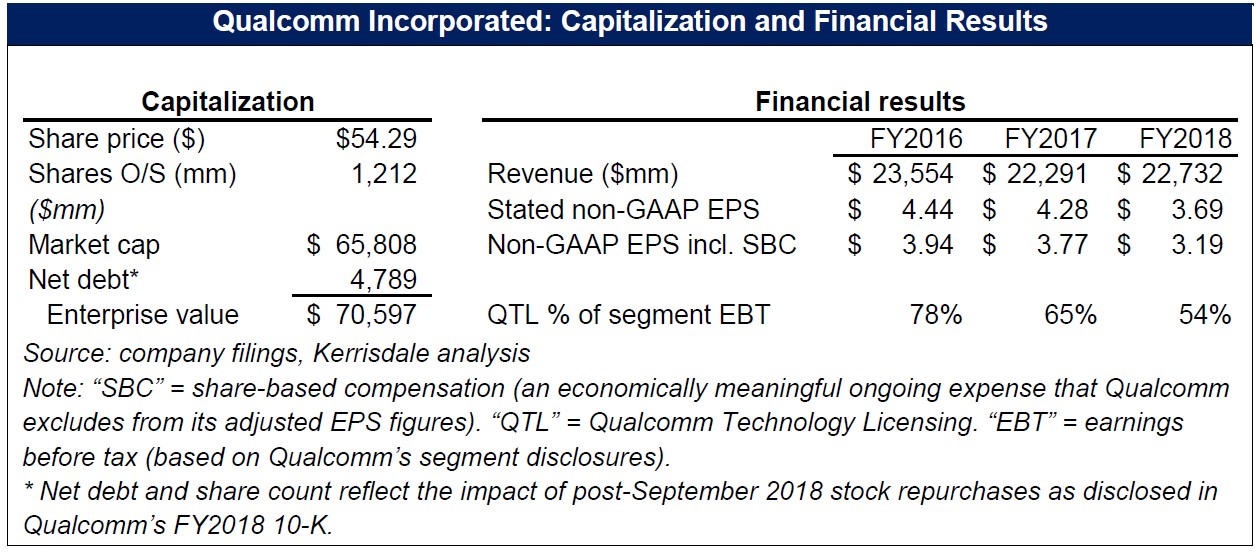

We are short shares of Qualcomm Incorporated, a semiconductor company teetering on the brink of disaster. For years, Qualcomm has presented itself as a technological innovator that monetizes its R&D in two ways: 1) selling chips that go into smartphones and other wireless devices and 2) licensing its patent portfolio. The licensing business, despite contributing far less revenue than the chip business, has historically supplied roughly two thirds of Qualcomm’s profits, thanks to its extremely high profit margins.

This unusual business model is living on borrowed time. In the past few years, regulators across the globe have concluded that Qualcomm’s ability to extract massive licensing fees from device-makers like Apple and Samsung stems not from the quality of its patents but from unlawful monopolistic tactics. In particular, authorities in China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Europe, and the United States have found fault with what they see as Qualcomm’s exploitation of its dominance in the market for premium modem chips (the components of smartphones that enable them to connect to cellular networks) to force device-makers to pay outrageously high patent royalties, even on devices that don’t contain Qualcomm chips, all while refusing to license its IP to potential competitors. These core Qualcomm business practices, regulators contend, violate binding pledges the company has made to license critical patents on “fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory” (FRAND) terms, including to rivals like Intel. Indeed, in the words of the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC), quoting an internal Qualcomm assessment from 2015, “granting a FRAND license to Intel ‘would destroy the whole current QTL [licensing] business.’”

If Qualcomm is right about that, then destruction is imminent. The FTC has brought a powerful legal case against the company, and the trial (conducted entirely before a judge, not a jury) is currently underway, with a scheduled end date of January 29th. We believe Qualcomm will lose, a view that we regard as the emerging consensus among informed observers, who have noted not just the strong evidence marshaled by the FTC but also the many instances before and during the trial when the judge signaled disagreement with Qualcomm’s legal views and even irritation with its lawyers.

Perhaps because prior legal troubles have “merely” cost Qualcomm billions of dollars without fundamentally transforming its business model, the market has failed to appreciate the potentially dire consequences of the current trial. If the judge grants the FTC the remedies it seeks, forcing Qualcomm, among other things, to license core patents to competitors and to renegotiate all of its existing licenses on fair terms, it could realistically cut Qualcomm’s licensing revenue, earnings power, and stock price in half. As Qualcomm’s long-running game of monopoly draws to a close, there will be no “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

Executive Summary

Qualcomm is very likely to lose its ongoing legal battle with the FTC. Judge Lucy Koh, who is presiding over the FTC v. Qualcomm trial, has already ruled against Qualcomm on several critical matters, including rejecting its motion to dismiss the case and pre-determining (on the FTC’s motion for partial summary judgment) that Qualcomm is indeed obligated, as a matter of contract law, to license its key (so-called standard-essential) cellular patents to potential competitors like Intel on FRAND terms. Meanwhile, in a closely related consumer class-action lawsuit, Judge Koh allowed the case to move forward despite Qualcomm’s vehement objections, characterizing the evidence presented thus far to show that Qualcomm’s anticompetitive practices harmed consumers as “copious,” “substantial,” and “significant.”1

None of this guarantees that Qualcomm will lose to the FTC, but we and other trial watchers have been impressed by the FTC’s performance and, by contrast, surprised at the sometimes combative interactions between Judge Koh and Qualcomm’s legal team. In general, government plaintiffs like the FTC enjoy a high win rate, and in this specific case the probability of government victory appears even higher than usual.

Ending Qualcomm’s unlawful business model will reset its long-term earnings power far lower. The FTC isn’t looking to fine Qualcomm; it’s looking to fundamentally change how the company does business. In particular, it’s seeking to force Qualcomm to license its most important patents on FRAND terms to competitors like Intel, with royalties set at a small percentage of the price of a modem chip rather than Qualcomm’s longstanding practice of charging device-makers a high percentage of the price of an entire phone. This shift alone will radically level the playing field, making the likes of Intel much more competitive, in part because of the legal doctrine of patent exhaustion. Under this doctrine, if Intel pays to license Qualcomm patents and then sells a chip that makes use of those patents to Apple or Samsung, Qualcomm has no legal right to demand any additional license fees from Apple or Samsung; once the initial license is granted, Qualcomm’s patent rights are “exhausted” (used up). This creates a troubling dynamic for Qualcomm: if Intel or MediaTek can market modem chips for, say, $20 plus a $1 license fee payable to Qualcomm ($21 all-in), how can Qualcomm continue to sell chips for the same ~$20 plus a smartphone-level license fee that could be as high as $20 on its own ($40 all-in)? The math doesn’t work. Thus Qualcomm will be compelled to drastically reduce what Apple has called its “extortion-level royalties”2 – plausibly by an order of magnitude.

Indeed, this dramatic shift may also unfold more directly if Judge Koh agrees to the FTC’s request to “[r]equire Qualcomm to negotiate or renegotiate, as applicable, license terms with customers in good faith under conditions free from” anticompetitive threats and “[r]equire Qualcomm to submit, as necessary, to arbitral or judicial dispute resolution to determine reasonable royalties and other license terms.”3 In other words, the judge’s decision in FTC v. Qualcomm – a decision that could come as soon as February – could trigger an immediate mass renegotiation in which Qualcomm is explicitly barred from leveraging its market position in modem chips to extract excessive, unfair royalties and in which any disagreement over what counts as “excessive” will likely end up back in court. But precedents for determining “reasonable royalties” in similar circumstances strongly disfavor Qualcomm (relative to its current monopolistic business model), pointing to a royalty rate that, according to one FTC expert witness, could be as low as ~0.6%,4 a rate likely applied to the modem price of tens of dollars as opposed to the device price of hundreds.

Even if we assume a far higher “fair” royalty of $1.50 per device – an amount that Apple’s chief operating officer said in sworn testimony that he proposed as relatively fair back in 20075 – we estimate that resetting Qualcomm’s licensing revenue to fair levels will slash revenue by $2.7 billion (relative to fiscal year 2018) and reduce run-rate diluted EPS to $1.64, implying a fair-value stock price of ~$21 based on historical Qualcomm and peer multiples – [[61%]] lower than the current price. Even in this scenario, Qualcomm would continue to siphon $2.5 billion per year out of the cellular industry – an amount that few outside of Qualcomm would likely view as unjustly paltry.

The prospect of such dramatic downside for Qualcomm’s “extortion-level royalties” isn’t surprising in light of some of the evidence that has already emerged from the FTC v. Qualcomm trial. Not only did Qualcomm say internally that licensing patents on FRAND terms to its competitor Intel – as Judge Koh may soon require – “would destroy the whole current QTL [licensing] business” (as quoted above); the FTC has also argued based on internal Qualcomm documents that a key reason Qualcomm repeatedly decided not to spin out its licensing unit as a separate company was that it wanted to retain the ability to leverage its modem-chip monopoly to extract supra-FRAND excessive royalties. But when Qualcomm is legally compelled not to leverage that monopoly, royalties will head much lower. Indeed, just last week the FTC confronted one of Qualcomm’s witnesses, the company’s senior vice president of licensing strategy, with his own past statement, recorded on audio tape, that when “having to choose between licensing chips and licensing at the handset, the handset was humongously more lucrative.”6 But this “humongously more lucrative” way of doing business – part and parcel of Qualcomm’s overall pattern of monopolistic tactics – will likely collapse when Judge Koh issues her final ruling.

Qualcomm’s broader business outlook is poor. Even completely disregarding the pivotal FTC case, Qualcomm is not a cheap stock; its current valuation seems to bake in an assumed near-term settlement of its complex legal and business disputes with two major customers, yet such a painless resolution appears less likely than ever. Meanwhile, against the backdrop of an increasingly saturated smartphone market, Qualcomm is facing growing competition from both rival chipmakers and its own customers (who are producing more key components in-house), suggesting lower market share and slower growth in the long run.

Company Overview

Founded in 1985, Qualcomm was an early innovator in wireless technology, pioneering the approach known as code-division multiple access (CDMA) and maintaining a strong position as a premier supplier of wireless modems and related components as 3G and 4G evolved. But while other suppliers of such components simply sell components, Qualcomm has divided its business into two key pieces: Qualcomm CDMA Technologies (QCT), a relatively straightforward operation that designs and sells wireless modem chips, and Qualcomm Technology Licensing (QTL), a hard-charging group devoted to getting the makers of smartphones and other wireless devices (known as original equipment manufacturers or OEMs) to pay licensing fees for access to Qualcomm’s large portfolio of patents. These patents include both standard-essential patents (SEPs), which Qualcomm has asserted are “essential” to the implementation of cellular technical standards like LTE, and non-SEPs that Qualcomm has developed or acquired and claims would be infringed by popular devices like the iPhone in the absence of a license. The FTC v. Qualcomm case has shown that the basic headline rate Qualcomm has historically charged for a license to its entire patent portfolio is 5% of the price of the entire device to which the license applies, with a recently imposed cap of $400 (implying a maximum royalty of 5% x $400 = $20 per device).

Like most semiconductor producers, QCT earns relatively low margins and is subject to major fluctuations in earnings based on the vagaries of product cycles and end-market demand. QTL, by contrast, used to boast pre-tax profit margins approaching 90%, as nearly every 3G and 4G device maker paid their “tax” on every unit shipped, with little manpower required to generate billions of dollars of revenue. But why? One might expect that hefty royalties charged to powerful OEMs would be met with stiffer resistance, with disagreements over patent validity and quality frequently descending into costly litigation. The puzzle grows when one considers that the cellular SEPs in Qualcomm’s portfolio – arguably the most important patents the company has – are encumbered by a FRAND pledge – that is, a contractual promise to a standard-setting organization like 3GPP (which writes the rules for standards like LTE and 5G) that Qualcomm will license those patents on “fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory” terms to all applicants. Such a pledge, though intentionally vague (with the definition of “FRAND” often determined, in the end, by a judge), is intended precisely to ensure that a patent holder like Qualcomm can’t extract excessive royalties from standards-implementers like OEMs and competing chipmakers. Nonetheless, QTL revenues and profits have achieved massive scale, with Qualcomm at one point bragging (in a slide presented at the trial) that its licensing revenue was larger than that of all other major licensing businesses in the world (including telecom titans Ericsson and Nokia) combined. Similarly, Huawei’s senior legal counsel testified that 80-90% of the company’s total patent licensing costs for mobile devices go to Qualcomm, despite the fact that Qualcomm is far from the only company that has made major contributions to 3G and 4G cellular standards. (Indeed, one FTC witness, an Ericsson employee, stated that, in terms of cellular SEPs, Qualcomm actually ranks below Ericsson (and likely Nokia as well).7) In other words, Qualcomm doesn’t hold anywhere near 80-90% of the most important cellular patents, yet it extracts the vast majority of the corresponding patent royalties.

In the opinion of regulators across the world, the reason Qualcomm has gotten away with this anomalously (indeed, “humongously”) lucrative licensing for so long is simple: it has such a dominant position in the markets for CDMA and premium LTE modem chips that OEMs, though regarding Qualcomm’s licensing fees as unfair and thus in violation of its FRAND commitments, felt they had no choice but to pay up. In theory, OEMs could have taken Qualcomm to court over its non-FRAND royalties from day one, but as a practical matter such a step posed too great a risk of Qualcomm retaliation via the QCT side of the business. The FTC’s opening statement in the current trial summarized this overall perspective and briefly explained why it violates US antitrust law:

This case concerns Qualcomm’s long-standing corporate policies to harm competition and consumers. Under those policies, Qualcomm will not sell modem chips to a customer unless the customer takes a separate license to Qualcomm’s standard-essential patents. The evidence will show that device manufacturers agreed to the license terms not because the royalty rates represent the fair value of Qualcomm’s patents but because they need access to Qualcomm’s modem chips. To buy Qualcomm’s modem chips, device manufacturers have to agree to pay Qualcomm’s elevated royalties, which are effectively a surcharge for access to Qualcomm’s chips, even when they use chips made by Qualcomm’s competitors.

As a matter of textbook economics, if a monopolist demands a substantial payment every time a customer buys from someone else, that payment harms competition and contributes to the maintenance of the monopolist’s market power. Under the FTC Act, that conduct is unlawful and warrants injunctive relief.8

In parallel with the FTC’s lawsuit, Qualcomm’s business relationships with key customers have also deteriorated: Apple has stopped using its chips and paying its allegedly non-FRAND royalties, and an additional OEM (universally believed to be Huawei) has also refused to pay. As a result, QTL revenues and profit margins have already dropped significantly.

However, investors have tended to take a sanguine view of these alarming developments, blithely assuming that rebellious OEMs will ultimately settle with Qualcomm on decent terms and that any adverse legal outcome will either result in minimal business-model disruptions or be overturned on appeal. This confidence is misplaced. In reality, the FTC case is going badly for Qualcomm, and the impact of a loss could be massive.

Qualcomm Is Very Likely to Lose Its Ongoing Legal Battle with the FTC

The FTC v. Qualcomm trial began on January 4th and is scheduled to end on the 29th; the judge will then issue her opinion afterwards, perhaps as soon as February, though she warned yesterday that it’s “going to take some time” (at least by her usual speedy standards). It’s easy for market participants to ignore complex court cases on the theory that there’s no way to estimate the probability of an adverse outcome, but for Qualcomm this facile view fails to recognize the evidence that we already have.

For one thing, Judge Koh has already made several decisions that required her to reject Qualcomm’s legal reasoning:

- Qualcomm initially moved to dismiss the FTC’s suit; Judge Koh said no.

- Qualcomm sought to present evidence regarding events subsequent to March 2018, the original discovery deadline in the case. Qualcomm believed that new developments like Apple’s abandonment of the company’s chips in favor of Intel’s would make Qualcomm’s historical business practices look less anticompetitive, but Judge Koh held fast to the original deadline.

- Most importantly, prior to the trial, the FTC moved for summary judgment on the legal question of whether the agreements Qualcomm made with standards-setting organizations regarding its FRAND commitments required it to license its SEPs to anyone, including competing chipmakers like Intel and MediaTek, or just to OEMs. Qualcomm maintained that it only needed to license its patents on FRAND terms to OEMs; at a minimum, Qualcomm said, the question of how far the FRAND commitment extended was difficult and controversial enough that it would need to be decided based on evidence presented at trial, not ahead of time. But Judge Koh disagreed, ruling that, as a matter of pure contract interpretation, Qualcomm was wrong, and, contrary to its longstanding practice, it actually is contractually obligated to license its SEPs on FRAND terms to anyone, including rivals. (Technically, Judge Koh’s ruling didn’t address the question of whether Qualcomm had actually breached this commitment, but, based on the evidence presented in the trial, it clearly has.) This landmark decision went a long way toward advancing the FTC’s case even before the trial began.

Furthermore, in a closely related antitrust class-action suit against Qualcomm – which, because it includes everyone in the United States who purchased a smartphone over a multi-year period, is likely the largest class action (in terms of number of class members) in US history – Judge Koh certified the class and thus allowed the suit to move forward, again over the strident objections of Qualcomm’s legal team. Her order in that case recounted in great detail the evidence that the plaintiffs had already presented to show that they had a plausible case that Qualcomm charged excessive, unfair, and unlawful patent royalties and that these excessive royalties were passed through to smartphone prices, pushing them up and thereby harming consumers; Judge Koh clearly believed the evidence was good enough to give the plaintiffs their day in court. While the legal issues at play in the FTC case are not identical to those in the class-action suit, it can’t be good for Qualcomm to see Judge Koh take such a favorable view of a body of evidence very similar to that set forth by the FTC. (For example, one of the FTC’s expert witnesses has also provided evidence in the class action, and his work is discussed very respectfully by Judge Koh.) The point is not that the judge is biased against Qualcomm but that Qualcomm’s legal arguments have repeatedly failed to persuade her – perhaps simply because the legal underpinnings of the company’s business practices are weak.

In addition, in a past case not directly involving Qualcomm, GPNE v. Apple, Judge Koh also ruled on a matter relevant to Qualcomm in a way that goes against its interests. The plaintiff, GPNE, purported to hold cellular SEPs (based on pager technology) and sued Apple for patent infringement. Apple submitted expert testimony in which the calculation of potential damages caused by this alleged infringement was based on a small percentage of the value of a standalone modem chip (also known as a baseband processor chip), not the entire value of, say, an iPhone. GPNE objected, in line with Qualcomm’s view of its own patents, that it was legally entitled to a royalty on the entire device and thus that Apple’s expert testimony should be thrown out. But Judge Koh disagreed, “hold[ing] as a matter of law that in this case, the baseband processor is the proper smallest salable patent-practicing unit”9 – in other words, the correct starting point or “royalty base” for calculating a reasonable royalty that, in turn, would dictate how much Apple would owe to GPNE if it was found to infringe on its patents. While the facts in the GPNE case don’t perfectly line up with the facts in the Qualcomm case, the similarities are strong; if Judge Koh concludes in one case that reasonable royalties on cellular SEPs should be a small fraction of the price of an individual modem chip, not an entire smartphone, then it’s difficult to see why she’d conclude differently in another case. Once again, this precedent does not bode well for Qualcomm.

See the full report below.