In mid-August 2016, I published a two-part series titled “Thinking about Thinking” (see Part I and II). Occasionally, I will be asked which WGR is my favorite or most important. I generally refer readers to the aforementioned reports.

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

One facet of that report is the three statements of knowledge—a priori analytic statements, a posteriori synthetic statements and a priori synthetic statements. The first are logic statements, where the subject is contained in the predicate. These statements are always true but generally trivial, essentially tautologies. To say “all unmarried men are bachelors” is true if one defines all bachelors as unmarried men. The second type of statements are inductive in nature. We observe the world and draw generalized conclusions about it. Such statements are always conditional. The concept of such statements was well described by Nicholas Taleb in The Black Swan.1 Ornithologists in Europe suggested that black swans didn’t exist because no one had ever seen one. Then, someone from Europe traveled to Australia and, lo and behold, black swans exist. A posteriori statements are true only until contrary evidence is found. Since science is built on induction, the notion of “settled science” is faulty; what we know from science is true based only on what we know now. But, if contrary evidence emerges, concepts based on induction must adjust.

The real battleground in philosophy are a priori synthetic statements. These are essentially “self-evident truths” that we believe to be true in all cases and are not derived from experience. The skeptical Scottish philosopher David Hume argued that a priori synthetic statements were not possible. Instead, he suggested that such statements were based on experience and thus a posteriori. Emmanuel Kant tried to rescue a priori synthetic statements by suggesting that humans were born with the ability to impose patterns of thinking on the world. In other words, we don’t actually perceive the world directly but we do so through the filter of one’s mind. This filter essentially impresses our views on reality and allows us to make a priori synthetic statements.

Although Kant’s attempt to “save” a priori synthetic statements has generally thought to have failed, there is an insight from Kant’s thought that is useful. Essentially, people tend to think in paradigms. In other words, we adopt a certain worldview or narrative for how things work and then impose them on reality. The problem is, of course, that our worldview or paradigm may not be true. In fact, almost by design, paradigms of reality are mere models and thus will be incomplete. At the same time, the paradigms we adopt shape how we interpret the world. Thus, it makes sense that we understand the models that we adopt to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses.

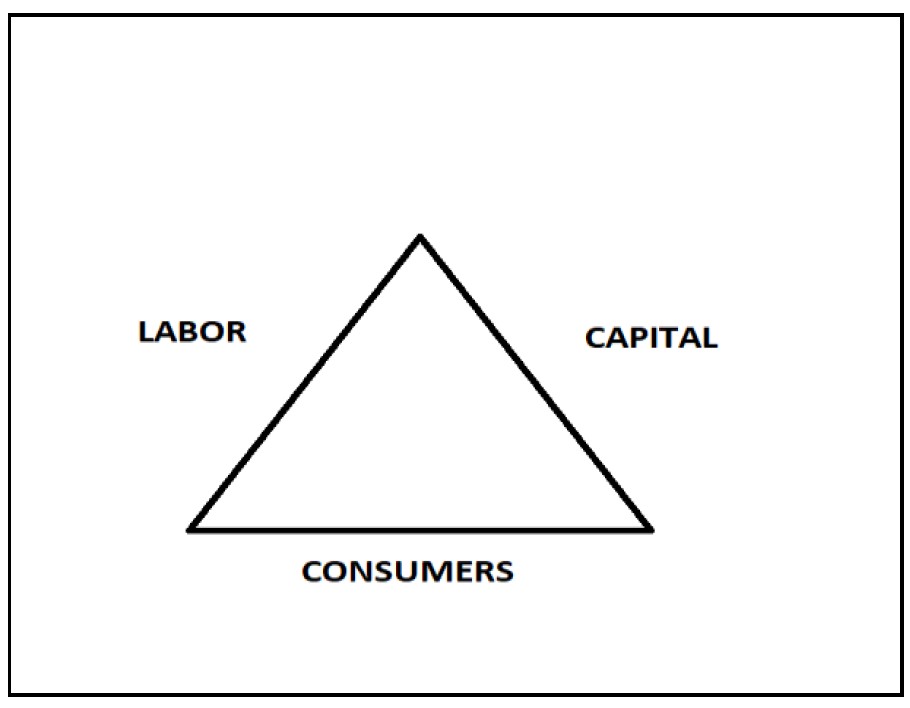

In this report, we will examine supply and demand as a model of markets and suggest that at the macro level a different model, the “Economic Triangle,” might offer better insights into how the political economy actually operates. We will discuss how the Economic Triangle explains the way various economic participants operate and how political factors affect the triangle. Next week, we will show how the Economic Triangle fits into the major economic systems, offer two contemporary examples, and conclude with market ramifications.

Supply and Demand

The paradigm of supply and demand is one of the most powerful in economics. It takes David Hume’s notion that the only factor that can overcome self-interest is self-interest. In other words, self-interest is the most powerful factor in human behavior, according to Hume, and it can be best controlled by pitting it against another’s self-interest.2 Adam Smith crystalized this idea in a famous passage:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but to their advantages.3

Essentially, the power of markets to align self-interest:

…by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.4

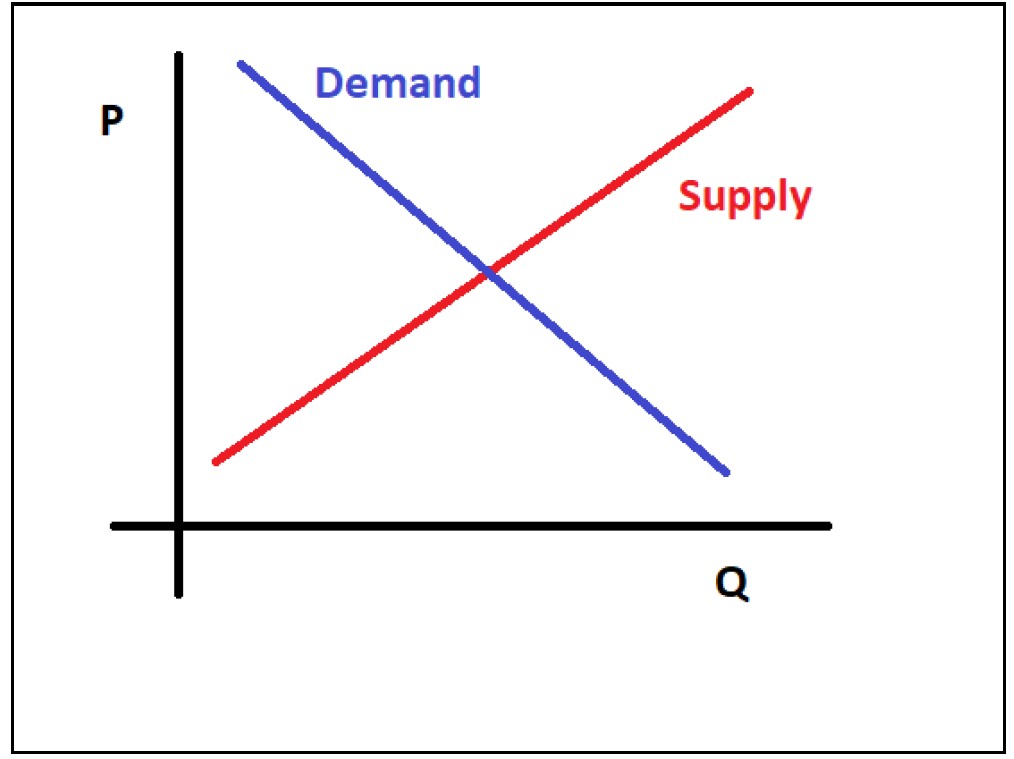

Economists since Hume and Smith further developed these themes and they evolved into what every Econ 101 student will recognize, the supply and demand curves.

The demand curve represents the consumers of a product or service. In general, we expect an inverse relationship to price and demand.5 Thus, a rising price will restrain demand. The supply curve represents the provider of a good or service. In general, we expect the supply provided to rise with a higher price. Both sides of the market have divergent interests. The price and quantity in the market is set at the intersection of the supply and demand curves. The market clears simply by the self-interested interaction of consumers and producers.

There is no quibble that the supply/demand model works well at the micro level. For individual consumers and firms, the model does a good job in describing behavior. However, there is a problem at the macro level. Macroeconomics adopted supply and demand for the whole economy, describing that model as aggregate demand and supply. However, the whole point of supply and demand analysis, based on the philosophical groundwork of Hume and Smith, is that the market is the clearinghouse for interests. The problem is that at the macro level the interests of consumers and producers are not easily delineated. The supply side is not a single entity but comprises capital and labor, whose interests are not identical. Consumers are not pure either; at the macro level, the income for consumers comes from profit, rent, and wages, or, put another way, from either being compensated by capital or by labor. Although aggregate supply and demand analysis does fit into Hicks’s neo-Keynesian model of the economy, the reality is that this model doesn’t truly reflect the coincidence of interests at the macro level as it does at the micro level. For example, the supply/demand model expresses the transaction of buying a bagel at a local coffee shop. As a consumer, I would prefer a free bagel; the proprietor would likely prefer to sell it for $100 each. We end up settling for a price of $2.50. The model is less effective in capturing the aggregate of the economy. As a consumer, I would prefer cheap goods; but if those goods are acquired by importing goods that deprive me of a job or reduce my pay, my interest are conflicted.

This is the problem that Marx tried to address. Marxism has never been able to create mathematically elegant economic models of classical or neo-Keynesian economics. But, what these models lack is the ability to fully express the divergence of interests that exist in the macroeconomy. The tensions tend to express themselves in the political arena and economics often fails to provide analysis that enlightens the discussion. Or, put another way, because economics is captured by the supply/demand paradigm, it struggles to examine conditions by any other method. For example, economics has tended to ignore the impact of power relations and usually reduces self-interest into merely the actions surrounding price. While that dovetails nicely into supply and demand analysis, it tends to reduce a complex set of relations that may prevent economists from fully appreciating social and political trends. Therefore, in light of this issue, our team has been thinking about a different model to examine the issue of interests.

The Economic Triangle

In discussions with my colleagues on this issue, Thomas Wash, staff economist, suggested that the interests of capital, labor, and consumers were better described as a triangle.

Here is how this analysis works. In an economy all members are consumers. Households are compensated by either the returns to capital or by wages. In general, household income is something of a continuum. Some households derive all their income from capital, more from labor, but many receive income from both sources in varying degrees. How a household views its interest is a combination of the fact that they are (a) consumers, and (b) receive income in varying degrees from capital and labor. It is fairly safe to assume that most households receive the majority of their income from labor (wages).

The returns to producers are divided between capital and labor. This is where the supply curve described above fails to fully portray the interests of producers. As we will describe below, the interests of both sides of production do not necessarily coincide. Broadly speaking, the interests of each break down as follows:

Consumers generally want the greatest amount of goods and services at the lowest possible cost. That is consistent with the downward sloping demand curve. Consumers may express some concern about the treatment of producers. Ethical buying campaigns and “fair value” campaigns are common. However, the preponderance of evidence supports the idea that the majority of consumers will purchase at the supplier who offers the lowest price. The fact that Walmart (WMT, 114.60) has put other general retailers out of business or Amazon (AMZN, 1,992.03) has decimated booksellers only occurred because consumers preferred low prices.

Labor generally wants the highest wage possible. They don’t necessarily care if consumers have to pay more or profits and rents decline. Of course, wage earners are also consumers so there is some interest in lower prices but, as individuals, labor wants the best wages they can get. In the aggregate, that leads to either higher prices or less margin for capital.

Capital is the most complicated of the three. The allocation of investment may be the most critical part of any economy because future growth depends on the proper creation of productive capacity. To create funds for investment, saving has to be created somewhere which requires the postponement of current consumption. A poor decision on investment means that current consumption has been postponed for no benefit and is thus lost to society. Political economics is, in part, based on who controls the ownership and allocation decision of investment. Private owners of capital tend to focus on profitability in determining investment. Public owners of capital, or private owners deeply influenced by government, may have other goals in addition to, or in substitution of, profits.

The Allocation of Interests

In Hume and Smith’s construction, self-interest is pitted against self-interest as the best way to achieve a peaceful, productive and efficient allocation of resources. However, what is often overlooked is that Hume said this was true if and only if the relative power of each side of the transaction was equal. For Hume, justice only exists between parties of nearly equal power. If wide power disparities exist, the weaker party can only rely on mercy.6

To counter this condition, governments have tended to intervene in order to balance out disparities of power between consumers, labor, and capital. As part of this process, theories of the political economy have developed throughout history to both guide and justify decisions that policymakers generate. In all of them, our position is that two of the three legs of the triangle can be favored at any given time. Or, put another way, there is a rank order of interests where one side of the triangle will be most favored, one second, and one last. Overall, the role of government has been to balance the interests of the three elements of the triangle to create an optimal economic and political outcome.

Part II

Next week, we will discuss the major theories of economics and how the Economic Triangle fits into those models. We will offer two contemporary examples to show how the theory works and conclude with market ramifications.

Article by Bill O’Grady of Confluence Investment Management LLC