Last week, we discussed Venezuela’s economic and political situations. Part II begins with a discussion on migration with a focus on emigrant flows. We include an analysis of the problems caused by migration followed by an examination of the possible end to this crisis and the broader geopolitical issues. As always, we will conclude with potential market ramifications.

[russia]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

The Migration

The total number of Venezuelans that live abroad is estimated to be between 4.0 and 4.5 million,1 roughly 13.5% of the country’s total population, suggesting that Venezuela has seen steady outflows due to the turmoil that Chavez’s revolution brought to the economy and political system. Since 2015, the International Organization for Migration estimates that 2.3 million Venezuelans have migrated, representing about 7% of the population. Surveys suggest that 54% of remaining upper income Venezuelans want to leave, while 43% of lower income citizens have the same goal.

In 2015, about 700,000 Venezuelans migrated, of which 73% arrived in the U.S., Canada or Europe. Their destinations would suggest these were probably upper income emigrants. Last year, 1.64 million migrated, with 53% staying in South America.2

Currently, the largest contingent is in Colombia, which is holding about 870,000 Venezuelan citizens. This number represents about 1.7% of Colombia’s population. This jump is a significant shock for Colombia. In 2010, a mere 100,000 foreigners lived in the country.3 The current influx is the largest inward migration in the country’s history and the massive migration is straining Colombia’s resources. In response, the U.S. has deployed the USNS Comfort to Colombia to assist in managing the refugees.4

Brazil has also seen a massive inflow of immigrants. It is estimated that up to 50,000 Venezuelans have moved to Brazil. To deal with the inflows, President Temer of Brazil has declared a “state of vulnerability5” in the border region of Rofaima and has increased border protection.6

Peru has also seen inflows. In 2015, the country had a mere 433 requests for refugee status; over the following two years, the numbers jumped to around 34,000. This year, the average is 14,000 per month. At the end of August, Peruvian authorities calculated that 400,000 Venezuelans are now living in the country.7

Ecuador has become a transit state for Venezuelans fleeing their country. Year to date, through August, authorities there indicated that about 641,000 Venezuelans have entered Ecuador. Of that cohort, about 526,000 have left for other places, while roughly 115,000 remain.8 Ecuador has concluded it doesn’t have the resources to cope with this influx. For Venezuelans with economic resources, the government will allow them to stay for up to two years. There are reports the government has organized bus trips for Venezuelan migrants that deposit them on the Peruvian frontier.9

The southern Caribbean islands of Curacao and Trinidad and Tobago have also become destinations for some migrants. Although the numbers are smaller compared to the other nearby states due to the difficulties of getting to the islands, there are still about 60,000 migrants living there, mostly on Trinidad and Tobago.10

Finally, Argentina and Chile also report a rising number of Venezuelan migrants. According to reports, a new Venezuelan refugee was showing up every 20 minutes in Argentina.11 But, their total numbers are not so high as to reflect the problems seen in Colombia and Brazil.

The Problems: Organized Crime

Mass migration can cause problems in the most stable of societies. We note recent elections in Sweden centered on issues of refugees and immigration.12 As noted above, the inflows into Colombia are massive. However, the disruption caused by this mass migration goes beyond just dealing with the influx of arrivals.

Venezuela is one of the most violent nations in the world; in 2016, the last reliable official data, more than 21,000 people were murdered, a rate of 70 murders per 100,000 people.13 Venezuela has the third highest murder rate in the world, trailing only El Salvador and Honduras.14 Organized crime is rampant in Venezuela, which is not uncommon in countries where the economy is failing and hyperinflation exists. Some analysis suggests that law enforcement is deeply involved in organized crime in Venezuela, participating in extortion, smuggling and other crimes.15

One of the key factors in organized crime in Venezuela is the widespread use of price controls and subsidies by the Maduro government. Price fixing on beef has led to cattle smuggling on a massive scale. It is estimated that 250,000 heads are diverted from Venezuela into Colombia each year to take advantage of higher market prices.16 Reports suggest that National Guard personnel are involved in the trade. Of course, the most egregious example of smuggling is petroleum, especially gasoline.17 Due to price controls and currency depreciation, some Venezuelans pay as little as $0.01 per liter, or about 3.78 cents per gallon.18 President Maduro, in a bid to reduce costs to the government, has called for moving prices to market levels.19 However, the government has issued citizens a “fatherland card” that allows holders to buy subsidized gasoline. Car owners have to register their vehicles with the state to be eligible. Registering the car and getting a card makes the holder dependent on the subsidy and is another way the government buys loyalty. Up to 100,000 barrels of oil or its equivalent is smuggled out of the country each day.20

Criminal gangs have reportedly moved into the mining sector. Working with corrupt security officials, these organizations are using mining not only to gain revenue but are also using mined precious metals to launder drug money. They are reportedly moving contraband metals via the same logistical networks used for transporting illegal drugs. And, they are also teaming up with other terrorist groups, such as Colombia’s FARC.21

Finally, these criminal organizations are preying on the desperate situations faced by the Venezuelan poor to engage in human trafficking, including sex work and forced labor.22 Firearms are said to be sold along the same smuggling routes.

The breakdown of civil order has led to widespread criminal behavior. As Venezuelans migrate, organized crime appears to be following them. In addition, criminal organizations in other countries are working with similar groups in Venezuela. As migration increases, the chances are elevated that Venezuelan criminal groups will continue to follow.

The Problems: Disease

As the Venezuelan economy has collapsed, basic medical care has become increasingly scarce. This is a dramatic turn of events; for years, Venezuela was on the forefront of tropical disease control. That is no longer the case.

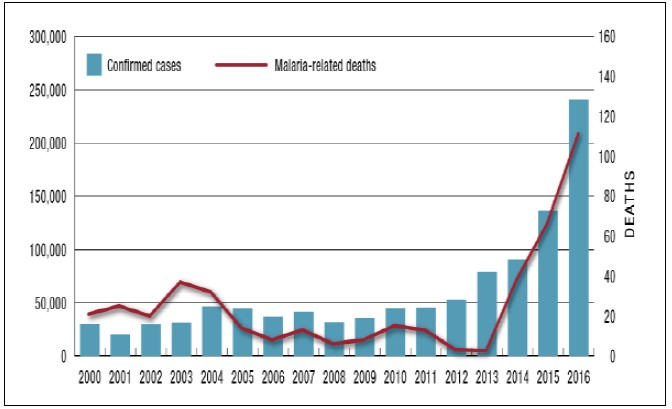

(Source: WHO Global Malaria Program)

By Q3 2017, the number of confirmed cases of malaria reached nearly 320,000. There are a number of reasons for the sharp increase. First, deforestation, some of which is caused by illegal mining, has created breeding grounds for mosquitos. Second, the economic crisis has made preventive measures unaffordable. Third, the drop in foreign reserves and the lack of imports have depleted medicine to treat the disease. Finally, what little medicine does come into the country is being diverted to the black market due to widespread corruption.

Measles has also returned to Venezuela.23 The collapse in public health due to the economic crisis has led to a shortfall of immunizations and an outbreak of the disease. A similar story has emerged on diphtheria.24 The decline in dollar reserves has sharply curtailed vaccine imports, ending public health vaccination programs.

As Venezuelans flee to other nations, they will invariably carry these illnesses with them. Non-governmental organizations have tried to bring medicines into the country. However, the Maduro government, skittish about outside interference, has interdicted the charity shipments.25 As Venezuelans migrate, rising crime and disease are risks to the host nations. These risks make the migrants unpopular and their already desperate situations worse.

No End in Sight

South America is no stranger to hyperinflation and debt default. Brazil suffered through economic crises in the 1980s and Argentina is a serial defaulter. However, Venezuela, in part due to its petroleum resources, has tended to avoid such problems.

In most cases, conditions deteriorate to the point where the military steps in and takes control. Authoritarian regimes usually follow coups but, eventually, democracy is restored. It would appear that most analysts, Venezuela’s neighbors and perhaps the U.S. expected history to repeat itself.

However, that hasn’t happened yet and there isn’t much evidence to suggest it will anytime soon. Although there is some evidence of discontent in the military (the recent drone attack is an example), Chavez’s relationship with the Castros tightened his control over the military. Chavez imported Cuban intelligence and internal security techniques which have proven effective in preventing threats to the regime from the military. In addition, the security forces are deeply involved in smuggling and corruption and thus appear willing to allow Maduro to remain in power. Maduro often cites fear of American interference and a U.S.-supported overthrow. Recent reports suggest the Trump administration had been in contact with dissidents in the military that were planning a coup26; however, the U.S. decided the group was unreliable and did not offer material support.

Russia and China have offered support to the Maduro administration. Russia has taken some stakes in the Venezuelan oil sector, including a 49% share of Citgo.27 It isn’t clear if such ownership would survive a change in government. Caracas has also restructured its debt with Moscow.28 Russia appears to value its relationship with Venezuela on geopolitical grounds rather than economic ones.

China has a more business-like relationship with the country. Venezuela owes around $15.0 bn to China, much of which is serviced directly through oil sales. Thus, falling production has raised concerns that Venezuela won’t be able to service the debt.

The involvement of Russia and China is seen as a threat to U.S. interests. At the same time, conditions in Venezuela are so dire that it doesn’t appear an outside power wants to take responsibility for fixing the country. Thus, Maduro could remain in power far longer than conditions would seem to permit. This factor alone is probably increasing the incentive for Venezuelans of all stripes to consider leaving.

Ramifications

The short-term worry is that the continued outflow of refugees out of Venezuela will trigger economic, security and health crises for its neighbors. These risks are already obvious. The temptation for these states is to follow the path of Ecuador and “encourage” Venezuelans to keep moving. It wouldn’t be a huge stretch of the imagination to see more Venezuelans attempt to make their way to the U.S. Already, wealthy Venezuelans have made it to the U.S.; America has nearly 59,000 Venezuelan asylum seekers.29 However, an influx of less affluent, more desperate and less healthy Venezuelan migrants into an already politically charged immigrant situation in the U.S. could be a serious problem. It’s possible that outcome may never happen. However, the U.S. should be taking steps, including aid, to support the countries currently bearing the burden.

Regarding market impact, the problems with Venezuela’s oil production are well known as are the issues with debt servicing. As for energy, the issue is that supply is becoming increasingly tenuous. The sanctions threat from the U.S. is already affecting Iranian output and it isn’t obvious if the Saudis can fill the gap. For the most part, the situation in Venezuela has been a slow-moving crisis simply because the problems are chronic. There is no doubt they are steadily getting worse, but we don’t see a complete collapse in the near term. On the other hand, the pressure being brought to bear on South America is weakening the case for this region’s emerging markets during a period when that asset class is struggling. It is an unwelcome development to see Venezuela’s problems becoming a regional issue.

Article by Bill O’Grady of Confluence Investment Management