Assessing profitability lies at the core of valuation and investment analysis, but it is far from straightforward. The most widely reported measure is profitability is return on equity, or ROE. The definition of ROE is

ROE = Net Income / Book Value of Equity.

[klarman]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

At one time this was probably a reasonable definition, but recent developments call both the numerator and dominator into question. Starting with the denominator, there has always been a problem because historical cost accounting may not properly reflect the value of depreciable assets. For example, it could be understated due to the impact of inflation.

But for modern companies there is a much more significant problem. Internally generated intangible assets are simply excluded from the balance sheet. For many companies, including the largest in the world by market capitalization, such internally generated intangible capital accounts for the lion’s share of total capital assets. For instance, the book values of equity for Apple and Microsoft are $115 billion and $83 billion, respectively. Whereas the market values of equity for the two companies are $1,069 billion and $830 billion. Much of the difference is due to the exclusion of internally generated intangible capital from the balance sheet. That capital can take many forms including: brand names, technical know-how, effective corporate organization, network effects and customer relationships.

It is one thing to recognize that internally generated capital is important, but quite another to estimate its magnitude. Given current accounting standards virtually all investments in intangible capital are run through the income statements as expenses. These have to be recategorized as investments. Some expenditures are clearly related to the production of intangible capital such as marketing, advertising, and research and development and thus are relatively easy to recategorize. However, the role of intangible capital is becoming pervasive and the expenditures associated with it harder to isolate. For instance, the formation of sophisticated, collaborative and creative work force is a type of intangible capital. Investment expenditure related to this capital is a part, but it is not clear what part, of compensation expense.

Another thing that makes taking account of intangible capital difficult is accounting for its depreciation. Whereas the impact of wear and tear on physical capital can be observed directly, how can the depreciation be estimated for intangibles? To complicate matters further, the depreciation schedule is likely to differ for various types of intangible capital.

Turning to the numerator, if intangibles are included as capital assets in an adjusted balance sheet, then expenditures related to the creation of intangibles must capitalized and added back to the income statement and the depreciation of intangibles must be deducted.

One way to estimate the importance of intangible capital is to replace the book value of equity by the market value when calculating ROE. That is define ROE(mkt) to be

ROE(mkt) = Net Income / Market Value of Equity.

The nice thing about this definition is that the market value of equity reflects the market’s assessment of the full value of intangible capital. If the company is sold, the buyer would have to recognize the market value of intangible capital on its balance sheet as goodwill. But there are two problems with the definition. First, it fails to adjust the measure of net income as described above. Because the adjustments to income will generally be positive, this leads to an understatement of the return on equity. Second, the market value of equity includes not only net investment in currently existing intangible capital, but also the market’s expectation of the value of future investments that will be made later. Thus the denominator is overstated, further reducing the estimated return on equity.

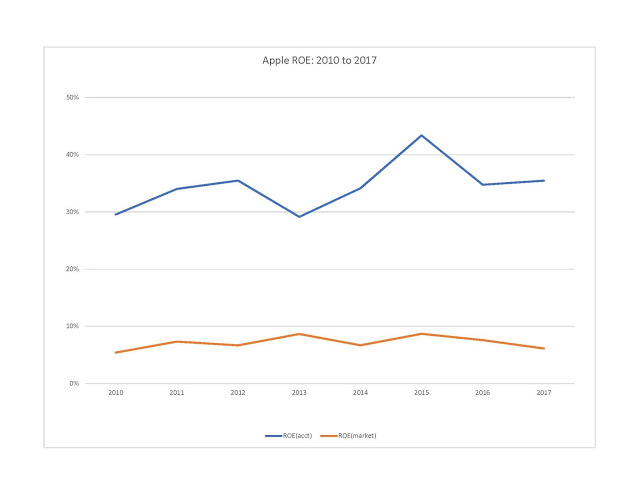

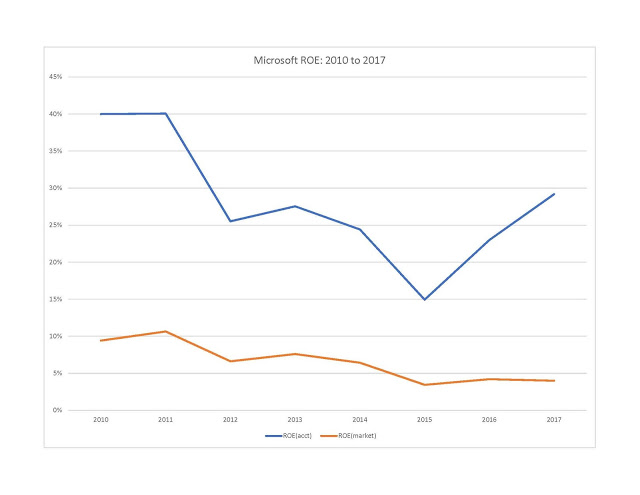

To provide some perspective on the importance of the foregoing issues, the exhibits below plot the annual return on equity measured relative to both book and market value for Apple and Microsoft. Both companies have extraordinarily high returns on book equity. Assuming that a fair estimate of the cost of equity capital is about 10%, it looks like the companies are earning far in excess of their cost of capital. But that is an illusion because the amount of capital is vastly understated by the exclusion of intangibles.

At the other extreme both companies are earning less than 10% on the market value of equity. But as noted above, this measure understates the true rate of return. The bottom line is that measuring the return on equity is no easy undertaking. Both obvious measures have significant deficiencies. Investors need to keep a sharp eye on profitability.

Article by Brad Cornell’s Economics Blog