- Joel Greenblatt documented his “Magic Formula” in 2005.

- His strategy showed 24% gains between 1988 and 2009.

- The last 8 years have shown much more ordinary returns.

- You can bring some of the sparkle back by adding a few new factors.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc, Also read Lear Capital: Financial Products You Should Avoid?

Joel Greenblatt published his magic formula in The Little Book That Beats The Market in 2005, in which he described a very simple stock selection system that in backtests showed 24% annual returns between 1998 and 2009.

Thousands of websites reference Greenblatt’s research and provide stock screeners and tips based on the formula, so it’s a popular subject and is enticing to those investors who want to follow a mechanical strategy.

But how has it fared since the book was published in 2005? I ran some research through the InvestorsEdge platform to find out (you can see more statistics and risk information together with individual position data for the backtests by clicking here).

Recent Performance

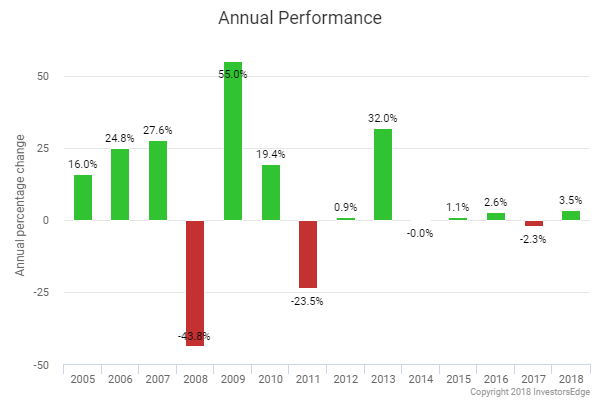

The polite answer to our performance question is “not that great”:

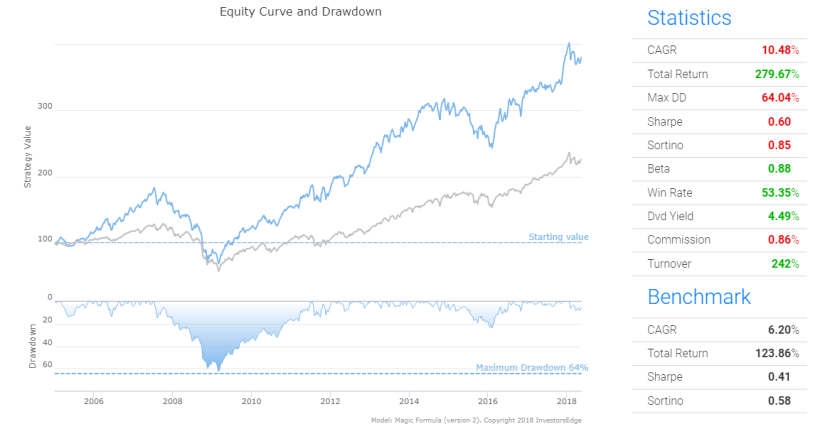

The first few years after the book was published showed on-track returns of 23% or so, 2008 showed an expected drop and 2009 saw the inevitable bounce back as prices and heart rates stabilized. However, from 2010 onwards the strategy has taken a downturn in fortunes that can be seen very clearly when you look at the strategy’s equity curve:

You can see the strategy would have returned just 5.5% over the period in question, a significant drop from the expected 24%. The culprit is the last four years where returns have barely broken even.

How The Strategy Worked

The strategy selects all stocks from the US and discards depository receipts, financials, utilities and any companies valued at less than $50m. It then ranks the resulting list by two factors:

- Earnings Yield

- Return On Capital (ROC)

Earnings Yield is calculated as Ebit / Enterprise Value, and tells us if a stock is trading at a good price or not.

Return On Capital is an efficiency ratio calculated by Ebit / (Average Total Assets – Average Current Liabilities) and shows us how efficiently a company utilizes its capital.

Each year the strategy selects the top 30 stocks in the list and holds them for the next 12 months, whereupon it rebalances and selects the top 30 stock from the new list.

So the strategy works on the basic principles that we select the most efficient companies with the cheapest relative valuations – so far so sensible.

What Went Wrong

One of the key problems with publishing the inner workings of a strategy is that the anomaly that you have discovered stops working.

Sometimes this is because it stops being an anomaly and becomes the default behavior for stocks, often because investors pile in and begin to buy and sell the same stocks at the same time.

2009 also saw a big change in the macroeconomic landscape – an abrupt change in sentiment during the financial crisis saw a whole series of historically profitable trading strategies become obsolete. The “death” (read underperformance) of value strategies in the last 6-7 years is a well-documented phenomenon on SeekingAlpha that the Magic Formula has fallen prey to as well.

Lastly, access to data and investor education has seen the more simplistic strategies relegated to the substitutes bench. It is not rocket science to state that efficient companies that are cheap will do well in the future, and we can identify candidate companies at the press of a button with the latest technologies.

So, can we evolve the Magic Formula to give it back some sparkle?

A New, Improved Magic Formula

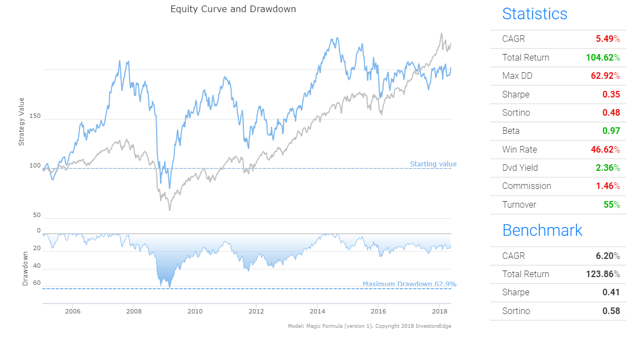

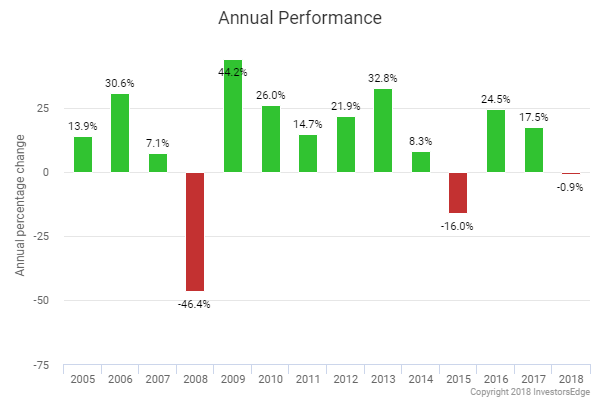

Well, yes – sort of. I’ve made four changes to the Magic Formula to improve returns:

- Drop the number of stocks bought each year from 30 to 20. This focuses the strategy on the most efficient and cheapest stocks.

- Rebalance more frequently. A lot can happen in a year – switching to rebalancing monthly allows stocks with poor results to be swapped with better candidates.

- Require stocks to have a Piotroski F Score of 6 or greater. The Piotroski Score is a value of 0 to 9 that assesses the quality of a company’s results.

- Add a third ranking factor, Dividend Yield. I often find you can use the fact a company pays a dividend as the sign of a healthy balance sheet, and quality dividend stocks have been in great demand over the last few years.

These new factors result in an improved set of results:

The average return throughout the 13-year backtest period was 10.5%, significantly better than the Greenblatt’s original version.

Conclusions

Greenblatt’s Magic Formula has shown poor returns since its release in 2005, partly because of a changing investment landscape and partly through the physical act of publication.

While you can evolve the basic concept to improve returns, I’ve documented other slightly more complex mechanical strategies here that have performed significantly better over the periods discussed here).

What this research does highlight is that strategies of all types, mechanical or other, do stop working, sometimes because of a change to the investing world and sometimes due to the strategy becoming a crowded place to trade in.

Article by Vintage Value Investing