One of the most important numbers in the world of finance and investing just hit a four-year high…

This week, the 10-year U.S. treasury yield rose to 3 percent for the first time since early 2014.

[REITs]

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

The 10-year U.S. treasury yield is one of the most important benchmark interest rates, and the most widely watched bond yield globally.

So even if you’re a stock person (or… especially if you’re a stock person who only kind of gets fixed income)… this is something you have to understand.

You see, every U.S. dollar-denominated debt instrument of any kind – all over the world – whether it’s a mortgage, a corporate bond or an asset-backed security, is benchmarked by investors to the U.S. treasury curve.

So if it’s a U.S. dollar instrument, then we compare its yield to its corresponding treasury “risk-free” rate in terms of valuing it.

For example, if I’m looking at a 10-year corporate bond, the first thing I’m going to compare it to is the equivalent 10-year U.S. treasury. I’ll compare its “spread”… that is, the additional yield it gives me over the treasury rate.

Often, when trading desks are dealing with credit products, like bonds or other credit instruments, the prices quoted between desks are simply quoted as spreads over the treasury curve.

Now, the reason the 10-year yield is so important is that the current outstanding value of the bond market in the U.S. alone sits at around US$40.8 trillion. That’s over twice the country’s GDP, and around US$10 trillion higher than the total U.S. equity market cap. It’s a very, very big number.

If the U.S. treasury curve (which is primarily assessed in terms of the 10-year yield) rises by 1 percent, then, all else equal (i.e., all credit spreads remaining the same), then EVERY single U.S. dollar bond will also experience a 1 percent rise in yield (and hence decline in price).

We’re talking tens of trillions of dollars here. The potential impact is huge. If a corporate bond is borrowing at 100 basis points (1 percent) over the treasury for 10 years, a rise from 2 to 3 percent in the treasury yield means an extra 1 percent of borrowing cost over 10 years. That extra debt servicing cost can hit right into the bottom line.

So why are U.S. treasury yields rising?

At the simplest level, yields rise when the market sells off bonds (bond prices and yields move in the opposite direction). That means bond market investors are essentially demanding more yield (a higher interest rate compensation, if you will) for lending 10-year money to the U.S. government.

One reason yields may rise is if perceived credit quality deteriorates. If investors think the chance of being repaid their principal has diminished, then they’ll need a higher yield to compensate them for the additional credit risk.

This is why when governments implement policies that will increase the budget deficit – that is, increase total expenditure or reduce receipts – we frequently see bond markets sell off.

Another reason we see yields rise is when inflation expectations rise.

If you hold long-term fixed income securities, like a 10-year treasury bond, then inflation can be deadly. Let’s say you buy a bond yielding 3 percent, but inflation shoots up to, say, 4 percent annually (from 2.5 percent when you bought the bond), then you’re left earning a negative real (i.e., inflation adjusted) interest rate.

The price of the bond will decline and the yield will increase to a level that the market is comfortable with again.

A final reason yields can rise is because of interest rate hikes, or the expectation of faster future interest rate hikes. These hikes are typically in response to an economy that is heating up and generating some inflation. Central banks act to pre-emptively cool the economy by raising the cost of capital, making it more expensive to borrow money.

The reason for the increase this time lies in a combination of the three above factors: Perceived deteriorating credit quality, increasing inflation expectations and interest rate hikes.

For example, U.S. President Donald Trump’s tax cuts are welcome on many fronts, but where’s the money coming from to pay for these cuts? It’s likely that the U.S. government is simply going to have to borrow more money to plug the gap.

Inflation expectations are likewise rising. The “5y5y forward inflation rate”, a derivatives-based indicator that gauges the annual level of inflation over five years, starting five years from now, has risen from as low as 2.1 percent mid-last year, to 2.45 percent currently.

And the price of crude oil futures are back at US$68 a barrel – prices last seen in late 2014. (A higher oil price typically means higher inflation.)

All of these factors combined are pushing up yields.

So is the bond bull market now truly over?

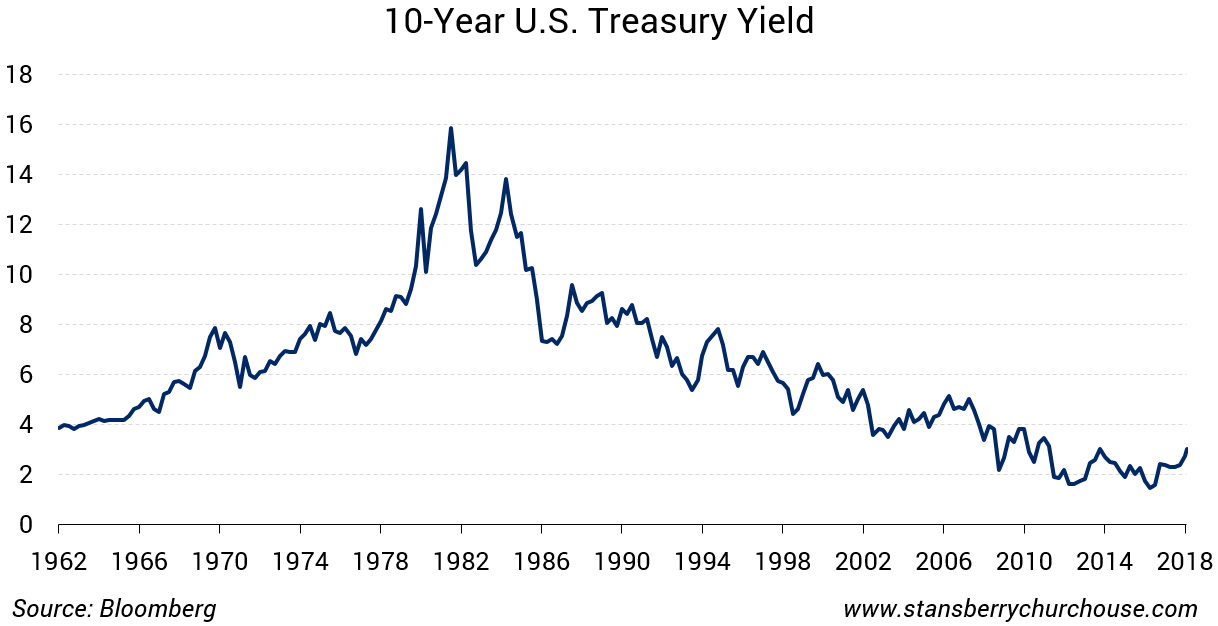

The chart below shows the historical 10-year yields all the way back to 1962. It’s clear that the low post-global financial crisis yields that have characterised the past half-decade arrived at the back of a multi-decade bull market in bonds (i.e. since the early 1980s, if you simply held bonds you would have done very well… yields go down, bond prices go up).

Trying to call the bottom in a generational bond market cycle isn’t particularly easy. You can be off by a few years and still, in the grand scheme of things, look pretty accurate when you’re looking at a 50-plus year time horizon.

So trying to make an outright call is tough. But it would appear that the risks to bond prices are skewed towards the downside (i.e., yields increasing), rather than the other way around.

So I’d recommend bond investors reduce their duration risk. I wrote a while back about how long-dated bond prices are highly sensitive to changes in interest rates. So if all treasury yields rise by 1 percent, for example, a 30-year bond will see a vastly sharper decline in price compared to, say, a two-year bond.

That means you should be rotating out of longer dated bonds into shorter dated ones. You don’t get all that much extra yield by extending your maturity anyway. The yield curve is quite flat. Right now, the 10-year treasury yields 3 percent. But you can earn 2.65 percent with a three-year bond.

So you lose a little bit of yield, but your interest rate risk is much lower.

With the three-year bond, your duration risk is 2.85. That means if interest rates rise by 1 percent, the price of your bond will fall by approximately 2.85 percent. Meanwhile, with the 10-year bond, you’re looking at a duration of 8.45. That means your bond price will fall by around three times more than the three-year bond for a 1 percent rise in interest rates.

So remember to keep an eye on your duration risk.

Good investing,

Tama

Article by Stansberry Churchouse