According to BRIC projections, the economic power of the BRICs is on the rise. But the other side of the coin is equally interesting. Among the G6 countries, US economic power is increasing at the expense of Europe and Japan.

[timeless]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Recently, the 10th BRICS Summit took place in Johannesburg, South Asia. As the international focus has been on the BRIC prospects in the future, it is often forgotten that when the first BRIC reports were published in the early 2000s, they also featured projections about the likely growth of major advanced economies.

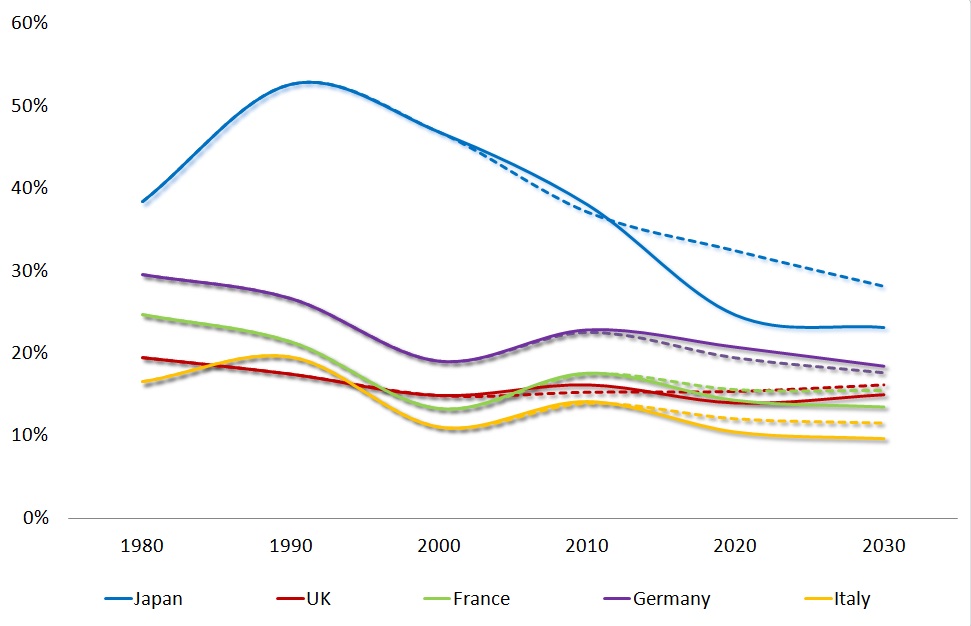

How have the leading Western economies fared in terms of those past expectations and current realities? In order to answer to that question, let’s use the largest economy, the United States, as a benchmark to compare the original BRIC analysis assumptions (dashed line) in the early 2000s with the advanced countries’ real economic development in the past two decades and the coming decade (Figure).

Figure 1: G6 Economies Relative to US Growth Performance, 1980-2030E

Sources: BRIC projections, Goldman Sachs, 2003; growth estimates, IMF; long-term growth projections, Difference Group.

Japan’s lost decades

Of the largest advanced economies, Japan’s economic agony has been the most painful one. Between 1980 and 1990, its share of the U.S. economy soared from 38% to 53%.

However, after Tokyo conceded to Washington’s demands in trade and currency disputes in the ‘80s, it was soon forced to cope with a huge asset bubble and the consequent secular stagnation.

Despite massive monetary injections, Japanese economy remains stagnant and government debt continues to soar (it’s now almost 255% of GDP).

Furthermore, the worst is still ahead in the next decade, as Japan must soon cope with a declining population.

In 2010, Japanese economy relative to the US had shrunk to a level where it had been in 1980. It is likely to decline further to 23% of the US economy by 2030 (some 5% more than the original BRIC estimate).

European erosion

What about the European economies? In 1980, Germany represented 30% of the US economy. Yet, the post-Cold War German unification did not bring the expected economic expansion, although it has fostered German leverage within the EU.

After unification turmoil, Chancellor Angela Merkel has steered her nation cautiously, smartly and shrewdly. However, now German economy is slowing, while political friction is increasing and the country has been targeted by Trump’s trade hawks. By 2030, German economy might prove to be just a fifth of the US economy (still about 2% more than expected).

Originally, BRIC projections assumed UK’s economic role to be nearly at par with Germany over time. Through Prime Minister Cameron’s reign, the UK was still pretty much on track with that scenario. However, the Brexit is likely to penalize Britain’s economic future by 2030 (- 2% relative to original projection).

In turn, the French economy was presumed to catch up with that of the UK in the future. In the early 2010s, it was still on track. However, the growth trajectory slipped toward the end of President Hollande’s reign. And despite great initial hopes, President Macron has not been able to restore France’s potential output scenario.

In Brussels, leading policymakers preferred center-right Berlusconi or center-left Matteo Renzi to Beppe Grillo’s radical-left Five Star Movement, which is now led by Luigi Di Maio, and radical right Northern League, which is steered by Matteo Salvini. The coalition government of the two is shunned in Brussels because it is euro-skeptical, against austerity and for debt relief (Rome’s sovereign debt is nearly 135% of its GDP). By 2030, Italy is likely to account less than a tenth of the US economy (-2% relative to original projection).

Expansive US, implosive Japan and EU

What’s amazing in this narrative about the absolute rise and relative decline of the G6 economies is that, in 1980, Japan (38%) and major European economies (16%-30% each) still accounted a major share of the US economy. However, if the current trends prevail, the relative proportion of each – Japan (23%) and EU economies (10%-19%) – will shrink significantly relative to the US GDP (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Japan and EU Economies Relative to US GDP, 1980-2030E

Sources: BRIC projections, Goldman Sachs, 2003; growth estimates, IMF; long-term growth projections, Difference Group.

That’s a story of extraordinary relative economic decline, which is often explained on the basis of misguided austerity, aging demographics and other policy failures. Yet, intriguingly, productivity levels among US, Europe and Japan are not that different and in innovation Japan is actually ahead of the US. Furthermore US sovereign debt now exceeds US economy (105% of GDP) and is thus close to the Italian level in 2008.

What’s worse, if the Trump administration will keep moving away from the postwar trading regime that Washington once created, bilateral and multilateral trade and investment conflicts will broaden, which has potential to deepen secular stagnation in most G6 economies, but particularly in Europe.

Perhaps it is not entirely without reason that euro-skeptics question the assumption that what’s good for America is good for Europe. That’s not the case in the early 21st century.

This is the second commentary based on Dr Steinbock’s recent briefing on the changes in G6 and BRIC growth trajectories.

Dr Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see http://www.differencegroup.net/