Finding more and better-trained workers is the top challenge for many US businesses. They say current workers can’t produce enough to meet growth objectives.

[timeless]

Q2 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

It’s true. Workers are key to economic growth, but it’s not the only factor. GDP growth requires some combination of:

- More workers,

- More hours of work from each worker, and/or

- More output per hour worked.

More workers aren’t in the cards. Demographics and reduced immigration seem to have capped labor force growth.

Average hours have climbed lately, which helps. Yet people can only work so much.

That leaves productivity as the main dial we can turn… but it hasn’t been working as well as it used to.

Since World War II, US worker productivity grew at 2.1% annually. However, in the last decade, it’s been hovering around 1.3%.

While this is a problem, solving it may not be as hard as it seems.

What Employers Could Do

There are several ways to raise productivity.

Businesses can help workers acquire new skills and work more efficiently. But training can be costly, so many prefer to hire workers who already have the desired skills.

Another way is to adopt technology that does the same tasks more efficiently than humans. This might result in layoffs, but the rest of humans will be more productive. However, technology is usually expensive and requires capital investment.

A third option is to entice more output from workers by connecting it to higher pay. Sell more widgets and you’ll get a quarterly bonus.

Employers like this because it is cost-free; they only spend more if they get more. In fact, lots of research shows “contingent motivators” tend to reduce productivity in the cognitive and creative jobs that increasingly drive the US economy. That’s not what businesses want, and it’s the opposite of what the economy needs.

Why Workers Are No Longer Motivated

Incentive pay can work in some situations. But it doesn’t work for sure if the workers do their part and the incentives don’t appear. This may be more common than we think. And it shows up in the economic data.

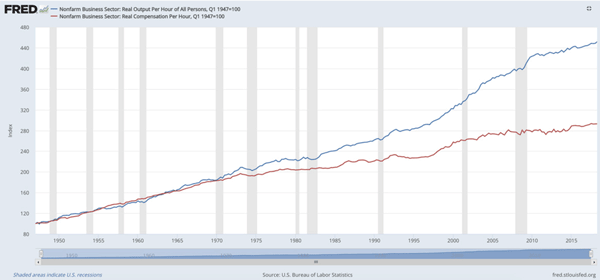

The chart below shows output per hour (blue line) and compensation per hour (red line), both adjusted for inflation. They are indexed so the 1947 level equals 100.

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank (Click to view larger)

You can see the two lines tracked closely for about 25 years after 1947. In total, American worker pay rose in line with worker productivity. Those were generally good economic times.

Then in the 1970s, something happened. The lines diverged. Worker productivity kept rising and even accelerated in the 1990s. Compensation rose too, but at a slower pace.

What happened? Economists aren’t sure.

Some think declining union membership left workers in weaker bargaining positions. Others point to factory automation. My own favorite is rising foreign competition after the 1971 end of the Bretton Woods monetary system launched a new era in international trade.

While causes are not defined, the effect is clear. Across the whole US economy, worker pay hasn’t kept up with worker productivity for some 40 years now.

That widening gap explains much of our political and cultural discord.

The Solution That Is Not Rocket Science

All this adds up to an odd situation.

After decades of becoming more productive and not seeing pay rise, productivity growth slowed down. It’s hard to unravel cause and effect, but a connection seems likely.

Yet people are still scratching their heads wondering why. And CEOs still complain they can’t find qualified workers.

This is no mystery. The solution isn’t rocket science either.

If businesses want more-skilled workers so they can produce more, they must teach them those skills. Either by themselves or by making sure schools have enough funding to provide it.

Then, when you get that additional productivity, share the fruits of it with workers.

But no.

Few businesses invest in training or support the tax increases it would take for schools to do it properly. Complaining while they wait for someone else to do the work is much easier.

Meanwhile, low productivity holds back higher growth that would help everyone.

The solution may be right in front of us, if we would only try it.

Get one of the world’s most widely read investment newsletters… free

Sharp macroeconomic analysis, big market calls, and shrewd predictions are all in a week’s work for visionary thinker and acclaimed financial expert John Mauldin. Since 2001, investors have turned to his Thoughts from the Frontline to be informed about what’s really going on in the economy. Join hundreds of thousands of readers, and get it free in your inbox every week.

Article by Mauldin Economics